Looking at findings across the survey, this study finds important evidence that voters believe there are genuine problems in the criminal justice system and subsequently support a range of arguments and policies designed to rectify these problems. Above all, voters want to see a criminal justice system that is fairer to all people and more focused on crime prevention and mental health and drug treatment than on overly lengthy punishments.

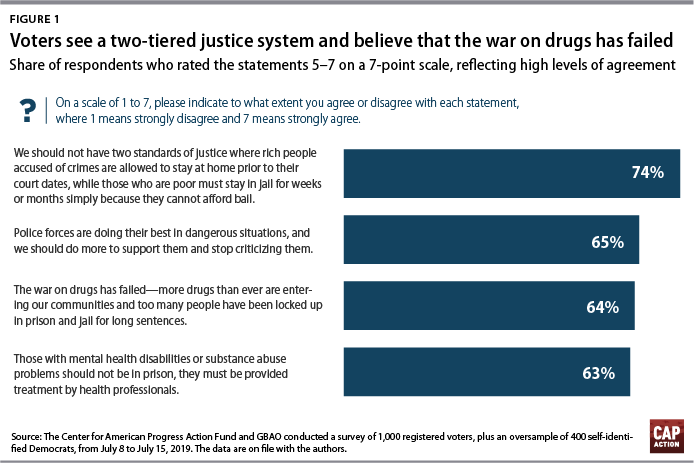

Examining a range of value propositions, majorities of American voters reject a two-tiered justice system that treats people differently based on income; believe that the war on drugs has failed; and want those with mental health disabilities or substance use challenges to have greater access to treatment by health professionals, rather than being incarcerated. The survey tested a series of value propositions about the criminal justice system, including a mix of common perspectives and ideas frequently put forth to frame these issues. Respondents were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with a particular statement, using a scale of 1 to 7, from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Figure 1 highlights the statements with the highest levels of agreement, indicating the total percentage of voters reporting a score of 5 to 7.

At the top of the list, with 74 percent agreement, is the idea: “We should not have two standards of justice where rich people accused of crimes are allowed to stay at home prior to their court dates, while those who are poor must stay in jail for weeks or months simply because they cannot afford bail.” Eighty-two percent of Democrats agree with this proposition, as do 67 percent of Republicans and 65 percent of independents.

Beyond the perceived unfairness of the pretrial system, nearly two-thirds of voters also agree that, “Police forces are doing their best in dangerous situations, and we should do more to support them and stop criticizing them.” This is driven by a high degree of Republican support for this statement, at 85 percent; 52 percent of Democrats similarly agree with this statement, with independents evenly split between agreeing and either disagreeing or being neutral. Likewise, majorities of white voters, at 70 percent, and African American voters, at 55 percent, believe that the police are doing their best in dangerous situations, with Latino voters in less agreement—at 47 percent.

Examining other top-tier value propositions with wide consensus, 64 percent of voters overall, including majorities across partisan and racial lines, agree with the argument: “The war on drugs has failed—more drugs than ever are entering our communities and too many people have been locked up in prison or jail for long sentences.” A roughly similar percentage of voters overall, 63 percent, also agree that, “Those with mental health disabilities or substance abuse problems should not be in prison, they must be provided treatment by health professionals.”

Majorities of voters across racial and partisan lines agree that the proper response for people with mental health disabilities and substance abuse challenges should be treatment rather than prison time.

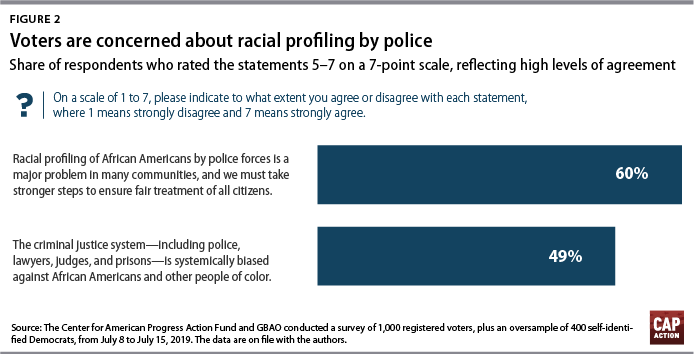

Most voters believe that racial profiling is a major problem and that the United States needs to do more to ensure fair treatment for all people. On the issue of racial bias in the criminal justice system, the study finds racial profiling to be of great concern to voters across demographic lines. Sixty percent of voters overall—including 53 percent of white voters, 87 percent of African American voters, and 64 percent of Latino voters—agree with the statement, “Racial profiling of African Americans by police forces is a major problem, and we must take stronger steps to ensure fair treatment of all citizens.” Partisan divides do emerge on the issue of racial profiling, however, with 80 percent of Democrats and 55 percent of independents agreeing that it is a major problem, compared with 37 percent of Republicans.

Although the specific issue of racial profiling concerns a wide swath of voters, less than half of all voters agree with a stronger critique: “The criminal justice system—including police, lawyers, judges, and prisons—is systemically biased against African Americans and other people of color.”

Racial splits are quite noticeable on this more substantial charge, with majorities of African Americans, at 81 percent, and Latinos, at 67 percent, agreeing that there is systemic bias in the criminal justice system, compared with just 4 in 10 white voters. Democrats overwhelmingly agree that the system is racially biased, at 72 percent, while less than half of independents—44 percent—and only one-quarter of Republicans agree.

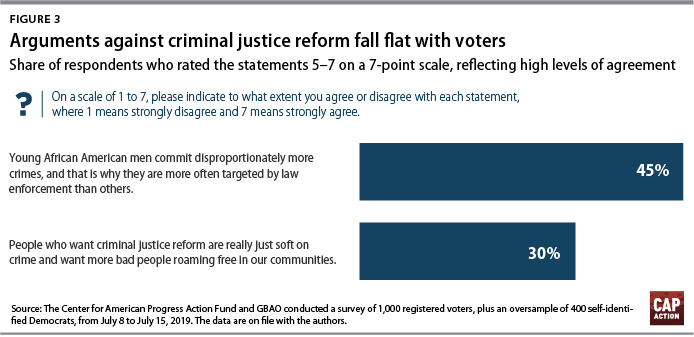

A majority of voters reject tough-on-crime and common racialized arguments against reform. At the same time, voters do not see reducing the total number of incarcerated people as a goal unto itself and fail to connect such reductions with increased safety in U.S. communities—establishing a need for leaders in criminal justice reform to affirmatively make that case.

The study finds that less than half of American voters—45 percent—agree with an argument frequently employed against reform that, “Young African American men commit disproportionately more crimes, and that is why they are more often targeted by law enforcement than others.” Similarly, less than half of all voters—46 percent—in a split sample test agree that “undocumented immigrants and other minority groups” disproportionately commit more crimes, leading to increased targeting by law enforcement. Democrats (37 percent) and independents (34 percent) are the least likely to agree that young African American men are targeted more by law enforcement because they commit more crimes, while Republicans report higher agreement, at 60 percent.

The anti-reform argument that “people who want criminal justice reform are really just soft on crime and want more bad people roaming free in our communities” is likewise rejected by large percentage of voters. Only 30 percent of voters overall agree with this description of the potential negative effects of reform efforts.

Although voters do not agree with this dire prediction about reform efforts, they fail to demonstrate support for the inverse in the following statement: “Reforming our criminal justice system by reducing the number of people who are arrested and incarcerated will help make our communities safe.” Only 39 percent of voters overall agree with this idea. Notably, majorities of African Americans (63 percent), Latinos (51 percent), and Democrats (51 percent) agree that reductions in arrests and incarcerations will improve safety in their communities.

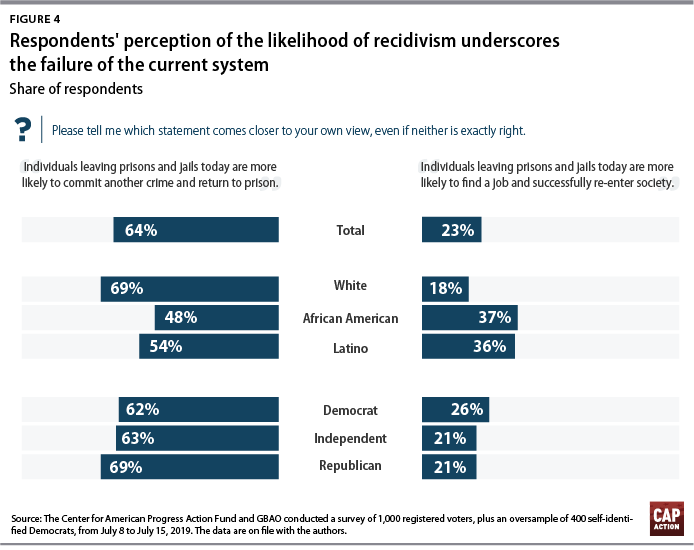

A strong majority of voters view the criminal justice as broken and ineffective in preparing people to successfully reenter society upon release. On the subject of whether the criminal justice system works as designed in terms of reducing crime and preventing recidivism, voters strongly believe that it does not. The study presented two contrasting statements and asked voters whether the first or second one comes closer to their own views, even if neither one is exactly right.

As seen in Figure 4, 64 percent of voters believe, “Individuals leaving prisons and jails today are more likely to commit another crime and return to prison,” versus 23 percent who believe, “Individuals leaving prisons and jails today are more likely to find a job and successfully re-enter society.”

Majorities of voters across party lines see recidivism, rather than successful reentry and employment, as the likely outcome for people leaving prisons or jails today. White voters and Republicans express the highest levels of agreement with this idea, both at 69 percent.

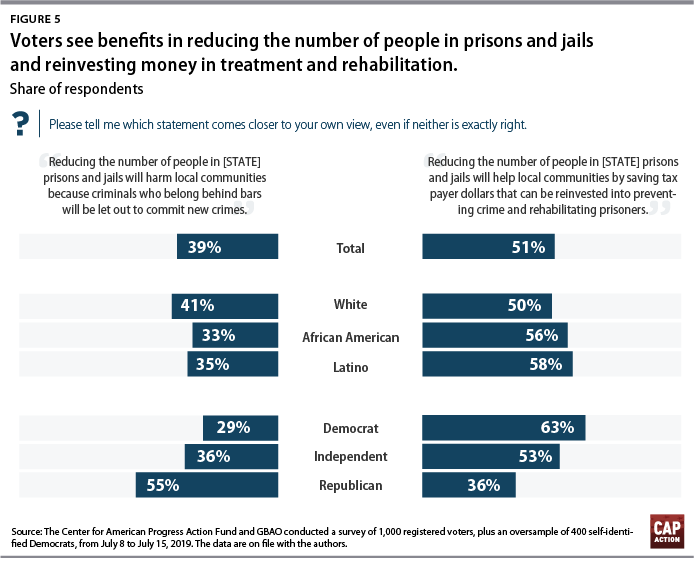

Voters believe that reductions in state prison populations will produce cost savings that can be channeled into more promising crime prevention and rehabilitation approaches. In another test between two statements, a majority of voters—51 percent—choose the idea that, “Reducing the number of people in (STATE) prisons and jails will help local communities by saving taxpayer dollars that can be reinvested into preventing crime and rehabilitating prisoners,” compared with 39 percent who favor the opposite idea: “Reducing the number of people in (STATE) prisons and jails will harm local communities because criminals who belong behind bars will be let out to commit new crimes.”

Voters across racial and ethnic lines are more likely to believe that reducing prison populations will save money that can be better spent on crime prevention and rehabilitation efforts, rather than the opposite notion that it will lead to more crime. However, a majority of Republicans—55 percent—believe the latter statement about increased crime, in contrast to the 53 percent of independents and 63 percent of Democrats who believe the former statement about cost savings.

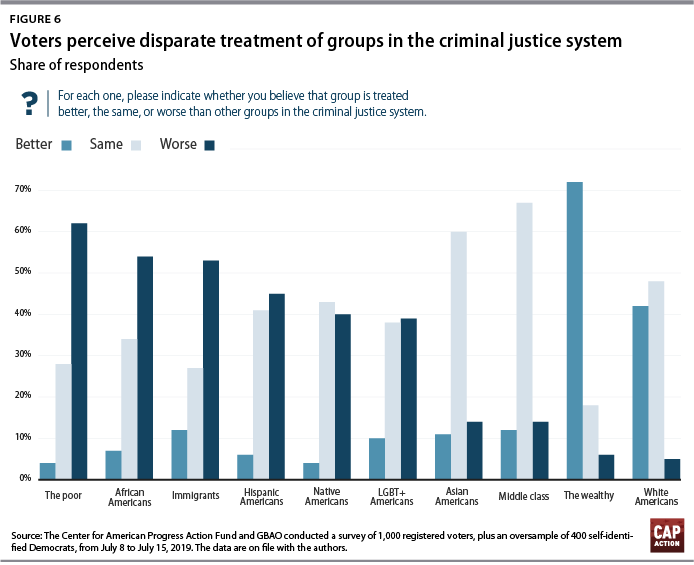

Majorities of American voters believe that those in poverty, African Americans, and immigrants are treated worse than other groups in the criminal justice system. The study presented voters with a list of demographic groups and asked them whether that particular group is treated “better, the same as, or worse than” other groups in the criminal justice system. As highlighted in Figure 6, 62 percent of voters overall believe that “the poor” are treated worse than others in the system, and majorities of voters feel similarly about “African Americans” and “immigrants”—at 54 percent and 53 percent, respectively. Voters across racial and partisan lines view each of these groups as receiving worse, rather than better, treatment than others.

Roughly 4 in 10 voters also believe that “Hispanic Americans,” “Native Americans,” and “LGBT+ Americans” receive worse treatment than others in the criminal justice system. Two-thirds of voters see “the middle class” as being treated the same as others, and 60 percent see “Asian Americans” receiving treatment equal to that of others.

On the opposite end, more than 7 in 10 voters see “the wealthy” as being treated better than others, with voters across demographic and party lines seeing the wealthy as getting better, rather than worse, treatment by wide margins.

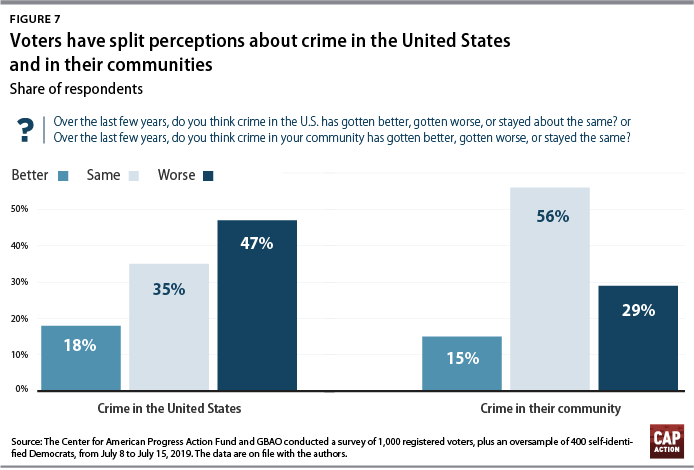

Voters believe that crime has gotten worse nationally over the past few years but that crime in their own communities has stayed the same. Looking at the larger context for debates on the criminal justice system, the study asked half of the voter sample whether they think “crime in the U.S.” has “gotten better,” “gotten worse,” or “stayed about the same,” and asked the other half of the sample whether “crime in your community” has “gotten better,” “gotten worse,” or “stayed about the same.”3

Despite the fact that data show a downward trend in crime rates nationwide,4 nearly half of voters—47 percent—believe that crime nationally has gotten worse over the past few years, with 35 percent saying it has stayed about the same and 18 percent saying it has gotten better. In contrast, a clear majority of voters—56 percent—report that crime in their communities has stayed about the same, with 29 percent saying it has gotten worse and 15 percent saying it has gotten better. (see Figure 7)

Partisan and demographic patterns emerge on perceptions about national crime, with Republicans (41 percent) and whites (45 percent) less likely than Democrats (58 percent), African Americans (54 percent), and Latinos (48 percent) to say that crime is getting worse nationally. African American and Latino voters are also slightly more likely than white voters to say that crime in their community has gotten worse over the past few years.

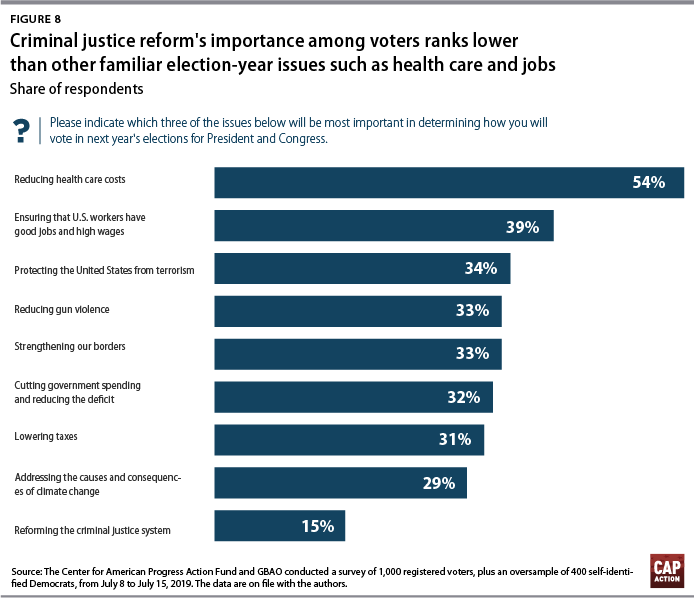

Compared with familiar election-year issues such as health care, jobs, and wages, criminal justice reform is a low priority for voters, but voters also report that they are not hearing much about it from 2020 presidential candidates. The survey presented respondents with a list of major issue priorities and asked them to indicate the three issues that will be most important to them in determining how they will vote in the upcoming elections. Figure 8 highlights the relative ranking of these issues, with health care clearly dominating voters’ minds overall: A full 54 percent of voters choose “reducing health care costs” as one of their top-three issues for next year’s elections. Jobs and wages rank second, with 39 percent of voters choosing the issue as a top priority, followed by a cluster of other security and domestic issues mentioned by around 3 in 10 voters. Health care costs top the list for nearly all partisan and demographic groups, with the exception of self-identified Republicans, who rank “strengthening our borders” and “protecting the U.S. from terrorism” above reducing health care costs.

“Reforming the criminal justice system” comes in low on the list of top priorities for next year, with only 15 percent of voters selecting it as one of their top-three issues for the upcoming elections. Among African Americans, a group disproportionately affected by these issues,5 28 percent rate criminal justice reform as one of their top-three priorities.

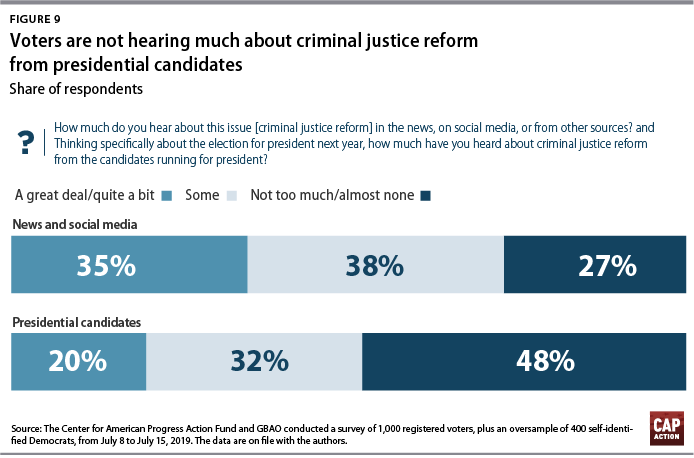

The relative saliency of the issue makes sense given the findings outlined in Figure 9. The survey asked people how much they have heard about the issue of criminal justice reform from the news and social media, as well as from presidential candidates. Overall, slightly more than one-third of voters—35 percent—said that they had heard either “a great deal” or “quite a bit” about criminal justice reform in the news or on social media, while only 20 percent of voters report heard “a great deal” or “quite a bit” from candidates. A full 48 percent of voters overall, and 44 percent of Democrats, said that they had heard little to nothing from presidential candidates on these issues.

It is worth noting that since the time this poll was conducted, several Democratic presidential candidates have released major criminal justice reform platforms, including Sen. Bernie Sanders (D-VT), former Vice President Joe Biden, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA).

African Americans and Latinos reported much higher levels of exposure to discussions of criminal justice issues in the news and on social media, compared with white voters: 47 percent of African American voters and 50 percent of Latino voters report hearing “quite a bit” or “a great deal” about the issue outside of the political arena.

The confusing nature of the term “criminal justice reform” also contributes to how voters rank this issue compared with other more commonly understood priorities. The survey asked respondents to describe in a few words what the term itself means to them. Responses varied widely, from ideas about sentencing reform and the drug war to more abstract discussions about justice and fairness to more counterintuitive opinions that the term meant increasing punishment and jail time for offenders.

Given these important, more qualitative findings, supporters of criminal justice reform need to spend additional time defining the issue overall. And perhaps more importantly, they need to sharpen their public arguments on what the debate about “criminal justice reform” substantively represents so that voters understand what they mean.

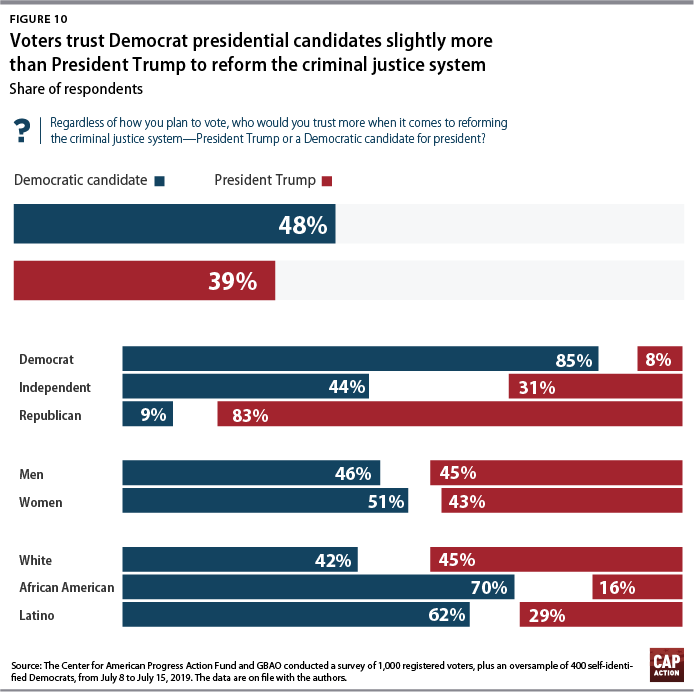

By a narrow margin, voters trust Democratic presidential candidates more than President Donald Trump to reform the criminal justice system. Despite the president’s low job approval ratings—53 percent disapproval among all voters6—the issue of criminal justice reform is still up for grabs. As seen in Figure 10, by a 48 to 39 percent margin, voters say that they trust Democratic candidates more than President Trump “when it comes to reforming the criminal justice system.”

Not surprisingly, perceptions of trust are sharply divided along partisan lines, with 85 percent of self-identified Democrats trusting Democratic candidates more on criminal justice reform, and a roughly similar proportion of self-identified Republicans, 83 percent, trusting President Trump more. Independent voters, however, are more divided, with 44 percent trusting Democrats more and 31 percent trusting President Trump more. White voters are essentially split on who they trust more to reform the criminal justice system—with 42 percent for Democrats and 45 percent for President Trump—while both African American and Latino voters express much higher levels of trust in Democratic candidates on the issue, at 70 percent and 62 percent, respectively.

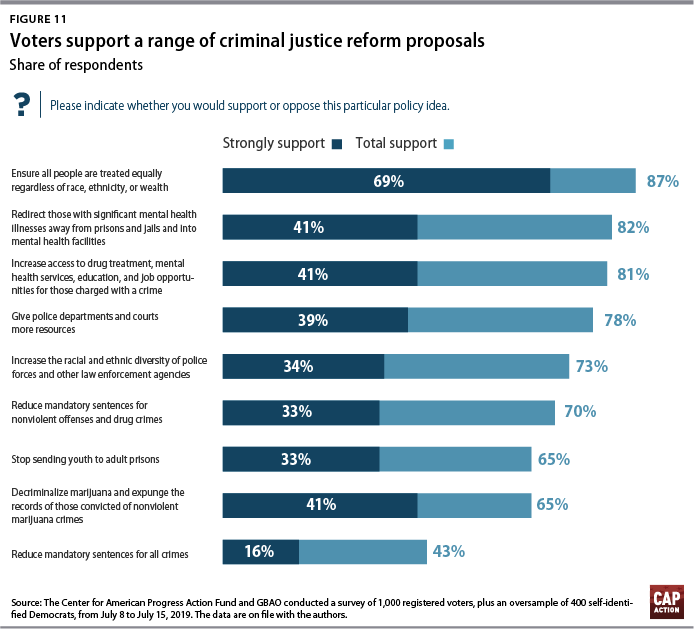

Reforms focused on equality, mental health and drug treatment, and crime prevention measures receive broad and intense support from voters. The study presented voters with a series of concise reform proposal ideas and asked them whether they support or oppose each of the measures. Looking at Figure 11, the reforms with the highest levels of overall support—ranging from 81 to 87 percent—are focused on increased fairness for all and a shift toward prevention and treatment over jail time.

Nearly 9 in 10 voters support the basic policy goal to “ensure all people are treated equally regardless of race, ethnicity, or wealth,” including 69 percent of voters who strongly support this basic policy approach. More than 8 in 10 voters back efforts to “redirect those with significant mental health illnesses away from prisons and jails and into mental health facilities,” as well as steps to “increase access to drug treatment, mental health services, education, and job opportunities for those charged with a crime.”

Approximately 7 in 10 voters overall support proposals to “increase the racial and ethnic diversity of police forces” and to “reduce mandatory sentences for non-violent offenses and drug crimes.” In addition, more than 6 in 10 voters support steps to “stop sending youth to adult prisons” and to “decriminalize marijuana and expunge the records of those convicted of non-violent marijuana offenses,” while a majority of voters support efforts to “eliminate cash bail.” In contrast, majorities of voters currently oppose more far-reaching proposals to “significantly reduce the number of Americans behind bars and close at least one prison in every state,” as well as a proposal to “reduce mandatory sentences for all crimes.”

Voters respond strongly to reform messages that emphasize comprehensive crime prevention. Voters were asked to evaluate a series of messaging frameworks in support of criminal justice reform and indicate whether they find each argument convincing. The strongest overall message connected prevention in the criminal justice system to similar efforts in the health care system:

A focus on prevention in health care helps to reduce costs and keep people healthier by focusing on problems before people get too sick. A similar focus on prevention in public safety would help to cut the high costs of incarceration while reducing crime in our communities by investing in good schools, affordable housing, job training, and drug or mental health treatment for those who need it.

Sixty-nine percent of voters overall, and 81 percent of Democrats, find this message convincing as a reason to support criminal justice reforms. Independents and Republicans also respond positively, with 64 percent and 60 percent finding it convincing, respectively.

As seen throughout these findings, American voters comprehend the extent of existing problems in the U.S. criminal justice system and are willing to support a range of new approaches to help ensure that the system works more effectively to prevent crime and treat those with mental health disabilities or substance use disorder, while better preparing those in prison to successfully reenter society and treating different groups of people more equally within the system itself.