America’s working- and middle-class families have had a rough time. For the past 30 years, they have been squeezed more and more by slow wage growth and rising costs. Even though worker productivity has risen substantially over the past three decades, American workers have seen their wages grow much more slowly. At the same time, the costs of key components of middle-class security have risen, placing the American dream farther out of reach. The economic pressure created by the squeeze of rising costs and stagnated worker pay is becoming especially harsh for low-wage workers: While inflation-adjusted incomes for the top 1 percent increased at a rate of 275 percent from 1979 to 2007, incomes for the bottom 20 percent of households increased at a rate of only 18 percent.

One of the most direct actions lawmakers can take to raise wages for low-wage workers is increasing the federal minimum wage. While an overwhelming majority of Americans show support for this push to increase worker pay, congressional gridlock has made federal action on the issue very difficult. In the face of a stalled Congress, states and localities have taken matters into their own hands. As of February, 29 states and the District of Columbia had set their minimum wages above the federal minimum wage.

Similar to states, cities have also taken the helm in tackling the rising inequality and wage stagnation faced by their residents. In particular, the higher cost of living in some cities places even greater economic pressures on many low-wage workers. This means that even state-level wage floors tend to fall short in providing living wages for workers who live in comparatively higher-cost cities. For example, while the minimum wage in the city of Los Angeles is higher than the federal minimum wage, a full-time, minimum-wage worker in Los Angeles still makes only $18,720 per year. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Living Wage Calculator, however, a family of three in Los Angeles needs $56,474 annually to meet minimum standards of living. In the city of Los Angeles, the typical monthly cost of housing for a worker with two children is $1,420, not to mention the typical monthly food bill of $536. Thus, the $1,560 monthly salary of a full-time, minimum-wage worker in Los Angeles does not even cover the cost of food and rent.

In recent years, several cities—such as San Francisco, California, and Santa Fe, New Mexico—have addressed this issue of affordability with ordinances and ballot measures that boost the local minimum wage. Since Washington, D.C., first increased its local minimum wage in 1993, 15 cities have followed suit. In fact, over the past two years alone, 13 cities and 4 counties have implemented local minimum-wage laws of their own, including Washington, D.C., which raised its minimum wage once again. Seattle is the most recent winner in the fight for fair wages, passing a measure to raise its minimum wage to $15 per hour over the course of three years to seven years, depending on the size of the employer. Other cities, such as Los Angeles and Kansas City, Missouri, are currently considering their own minimum-wage proposals.

While city minimum-wage laws are beginning to pick up steam, relatively little research on their economic impact is readily available. This issue brief takes a closer look into this trend and assesses the economic effects of local minimum-wage hikes. This brief provides both new Center for American Progress Action Fund analysis and uses existing literature to illustrate the effect that local minimum-wage hikes could have on economic development in and around affected regions. More specifically, the brief looks at:

- How historically inadequate minimum-wage levels have contributed to inequality and how raising these levels can actually reduce inequality

- The historical impact that minimum-wage increases have had on employment levels in and around affected areas

Where possible, the analysis in this brief uses literature that applies research methods that are specific to localities. It is important to note that because local minimum-wage hikes are a relatively new trend, not enough time has passed to allow for an extensive amount of rigorous research on their impact. Due to these limitations, the brief draws upon a larger body of academic literature that measures the impact of minimum-wage laws at both the state and federal level.

Impact on wages

For approximately 30 years after World War II, America’s working- and middle-class families did well and were able to share in the growing prosperity of the nation. From 1948 to the mid-1970s, wages for workers increased at a similar rate to productivity. However, starting in the late 1970s, workers began seeing slower wage growth, even as productivity growth continued to rise quickly. From 1979 to 2012, productivity grew 64.9 percent, but hourly compensation for nonsupervisory employees, who make up 80 percent of the private-sector workforce, grew only 8.2 percent.

While middle-class families have been hit hard on wages for the past 30 years, the situation is even worse when looking at total market income. Between 1979 and 2007, inflation-adjusted incomes for the households in the middle quintile increased at a rate of nearly 40 percent, and incomes for the bottom 20 percent increased 18 percent. At the same time, inflation-adjusted incomes for the top 1 percent grew at a rate of 275 percent. This trend in slow income growth for households at the bottom is largely the result of slow hourly wage growth for those households. Because wage-related income accounts for the vast majority of total market income for those at or near the bottom of the income distribution, slow hourly wage growth has become an especially challenging hurdle for these workers.

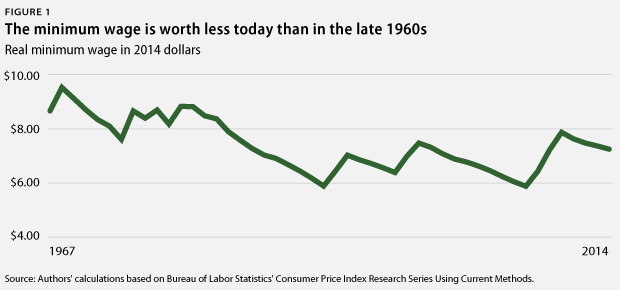

One reason those at the bottom of the wage distribution continue to face this downward pressure is the erosion of the minimum wage. The federal minimum wage has not kept up with inflation, and it is worth far less today than in the late 1960s. If the federal minimum wage had kept up with inflation since 1968, it would stand at $10.88 per hour in 2014 dollars. Moreover, other estimates show that if the federal minimum wage had kept up with productivity, it would be approximately $22 per hour in 2014 dollars. Research has also shown that the decline in the minimum wage’s real value contributes to the rise in inequality. In fact, the declining real value of the minimum wage explained more than half of the expansion of the 50-10 wage gap—the gap between median-wage workers and the bottom 10 percent —from 1979 to 2009.

Impact on employment levels

The effect that raising the minimum wage has on employment levels has become a highly contentious debate. Minimum-wage opponents often argue that raising the minimum wage increases labor costs on employers, thereby forcing them to fire workers or preventing them from hiring more workers. However, a growing amount of credible economic research undercuts this argument by showing that previous minimum-wage increases did not kill jobs.

Rigorous academic studies on state-level minimum-wage hikes support these findings and suggest that raising the minimum wage does not negatively affect employment levels. The most recent of these studies are regarded as some of the most methodologically accurate to date. Unlike older studies, they control for various regional and heterogeneous trends along U.S. Census Bureau divisions. For example, one of these studies published by the Center for Labor Research and Education at the University of California, Berkeley, analyzed employment effects for bordering counties across state lines that had different minimum wages. The authors of the study—Arindrajit Dube, T. William Lester, and Michael Reich—found that state-level minimum-wage increases have no discernible effect on employment levels. Furthermore, a previous CAP Action analysis provided a simple way to examine the employment effect of minimum-wage increases on a state-by-state basis. That analysis included each effective minimum-wage increase for every state during times of high unemployment—at least 7 percent—from 1987 through 2012. The authors then examined changes in employment over the year following the effective increase. According to the analysis, the majority of states that raised the minimum wage during this time period actually saw a decrease in their unemployment rate over the next year.

This brief mimics the previous state-by-state CAP Action analysis in order to examine the effect that local minimum-wage increases have on employment levels within cities, specifically Albuquerque and Santa Fe, New Mexico; San Francisco and San Jose, California; and Washington, D.C. Unemployment levels were examined within cities during the quarter of the enactment of the local minimum-wage increase and one year after its full implementation. The analysis for this brief included every citywide minimum-wage increase between 1993, when the first local increase was implemented, and 2013, the final year with measureable impact. The analysis includes every effective hike for the five study cities. (see Figure 2) Because city minimum-wage increases are a relatively new trend, there are a very small number of cities that have measurable impact. The authors anticipate reviewing this analysis again when enough time has passed since the recent municipal wage hikes.

The new findings are consistent with CAP’s previous state-by-state analysis. The analysis reveals that in 64 percent of the local minimum-wage hikes, the local unemployment rate did not increase one year after the increase. In fact, a majority of cities that increased their minimum wages saw their unemployment rates decline just one year later. From 1993 through 2013, cities raised their minimum wages a total of 25 times. Of those 25 instances, the corresponding city’s unemployment rate actually fell in 16 of the cases. There were nine cases in which the city unemployment rate increased, most of which occurred during the Great Recession. A separate analysis based on unemployment levels for the quarter before the effective minimum-wage increase and one year after full implementation produced similar results: The local unemployment rate did not increase in 56 percent of local minimum-wage hikes.

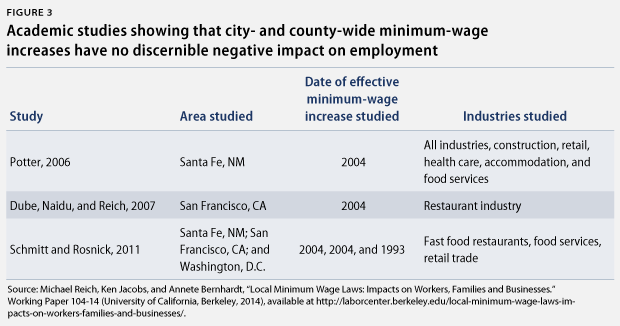

It is important to reiterate that data limitations have narrowed this analysis to a relatively small number of cases, and it does not contain the controls used in academic research. Indeed, more rigorous research is needed to truly capture the effect, if any, that local minimum-wage hikes have on employment levels. It will take time to build academically rigorous studies based on the recent local minimum-wage increases in order to measure their full effects. While little current research exists on local minimum-wage increases, there are three rigorous studies (see Figure 3) that use quasi-experimental research designs to measure the employment effect of citywide minimum-wage increases. Consistent with existing detailed state-level analyses, all three studies found that citywide and countywide minimum-wage increases have no discernible negative impact on employment levels. While there are studies that support the arguments of minimum-wage opponents, these studies are industry-backed and offer questionable methodological approaches.

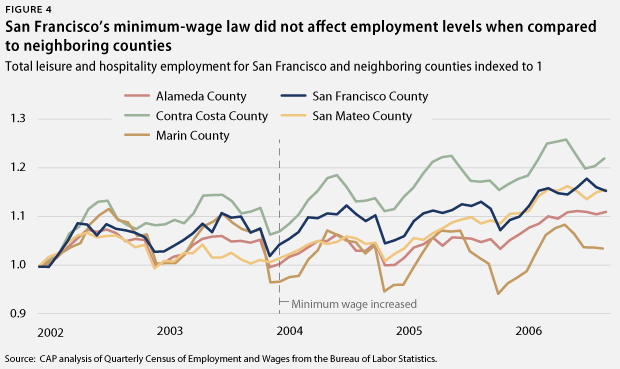

One of these three studies by Arindrajit Dube, Suresh Naidu, and Michael Reich used San Francisco’s 2004 minimum-wage increase to examine the effects of citywide increases. The trio of researchers used data from a commissioned panel’s survey of restaurants in San Francisco and cities within the neighboring East Bay region to study a wide range of economic outcomes. This allowed for a direct comparison of outcomes between San Francisco and neighboring cities that were not affected by the law. Economic outcomes included average hourly pay, total employment, part-time and full employment, menu prices, employee tenure, health insurance coverage, the proportion of workers who receive tips, and employer compliance. After controlling for various confounding factors, the authors found that there was no statistically significant evidence that linked negative effects on employment levels to San Francisco’s minimum-wage increase.

Dube and his colleagues also measured the regional employment impact of San Francisco’s minimum-wage increase by comparing the county-level trends in total restaurant employment for San Francisco County to neighboring Alameda County. The analysis for this brief borrows from this approach by comparing county-level trends in total employment for leisure and hospitality, though CAP Action examined San Francisco County’s other neighboring counties, Contra Costa, Marin, and San Mateo. Similar to Dube, Naidu, and Reich, CAP Action researchers used county-level data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, or QCEW, and examined the period two years before and after the initial minimum-wage increase in February 2004. CAP Action’s analysis ends in December 2006 because California raised its state minimum wage in January 2007.

According to this CAP Action analysis, all five counties experienced roughly similar leisure and hospitality employment growth before the February 2004 minimum-wage increase—though some counties, such as Marin, displayed more seasonal variation. Over the next two years, San Francisco had less job growth than Contra Costa County, which appeared to be growing slightly faster before the minimum-wage increase; roughly the same growth as San Mateo County; and more job growth than Alameda and Marin counties.

Conclusion

Although the analysis conducted for this brief does not provide conclusive evidence on its own, these initial examinations of local minimum-wage hikes—combined with existing academic studies—undermine conservative arguments that raising the minimum wage would cause job loss. Rather, it shows that the unemployment rate fell after 64 percent of the recent, measureable local minimum-wage increases. While more research into the impact of local minimum wages is needed, this initial finding should provide some welcome news to the cities and counties exploring a minimum-wage increase as a concrete measure to combat income inequality in their regions and to raise wages for workers.

Anna Chu is the Vice President for Policy and Research at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Jackie Odum is a Research Assistant and Brendan V. Duke is a Policy Analyst for the Economic Policy team at the Action Fund.

The authors would like to thank Ethan Gurwitz and Keegan Brown for their contributions to this report.