Ohio’s middle class is not as strong as it once was. While the state’s economy has experienced growth throughout the past 30 years, middle- and working-class families have seen little benefit as the majority of gains have flowed to those at the very top of the economic ladder. Real household incomes for the middle class are still nowhere near their prerecession levels; in fact, they are less today than they were in the 1980s. Meanwhile, the share of income going to the top 1 percent of earners continues to climb. These trends are concerning but reversible. Public policies aimed at strengthening the economy for those in the middle and at the bottom, rather than only those at the top, can help Ohio’s middle class become strong once again.

Ohio’s middle class has not seen the benefits of economic gains

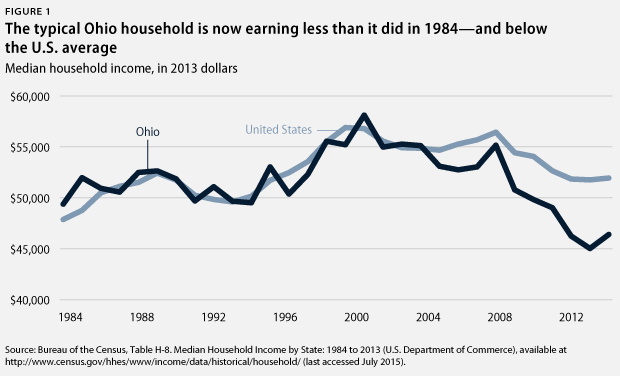

One of the clearest indicators of Ohio’s inequitable growth is median household income across the state. In 2013, the most recent year for which comparable data are available, a typical Ohioan household earned $46,398—less than it earned in 1984, the earliest year for which data are available. Ohio households did see a slight increase in median income in 2013, up from $45,020 in 2012. Yet there is significant room for improvement. Even in 2007, before the recession began, the median household income in 2013 dollars was $55,162—still lower than its peak of $58,115 in 2000.

While the recession caused household incomes to drop across the United States, the decline in Ohio was especially pronounced. Median household income in Ohio roughly kept pace with the U.S. average until about 2007, when the state diverged from the country-wide average in the fallout from the Great Recession. In 2013, the median household income in Ohio was $46,398, while the average for the United States was $51,939.

High levels of inequality in Ohio are not a result of a poor overall state economy. Over the same time period that median household income declined by 6 percent—1984 to 2013—personal income per capita—a commonly used measure of a state’s economy—increased by 57.8 percent in inflation-adjusted terms. The real reason this growth has not translated into gains for the middle and working classes is that an increasingly large share of the state’s economic gains has been directed to those at the top.

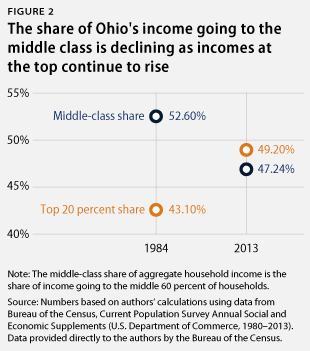

Over the past 30 years, the share of the total income generated across Ohio that has gone to the middle class has declined sharply. In 1984, the middle 60 percent of Ohioan households took home 52.6 percent of the state’s collective income. By 2013, the share of income taken home by the middle 60 percent of households had fallen to just 47.2 percent, a drop of more than 5 percentage points. Income shares to the bottom 20 percent also declined by 17 percent over the same period. Meanwhile, the top 20 percent’s share of income rose from 43.1 percent to 49.2 percent—meaning that one-fifth of Ohio residents took home nearly half of the total income generated across the state.

Even at the top, income is concentrated among the very few. A recent Economic Policy Institute study of state income growth using tax data found that a large share of the recovery gains have gone to the top 1 percent. The top 1 percent of earners captured 71.9 percent of the total income growth in Ohio from 2009 to 2012, reaching an average level of income that was approximately 21 times greater than the average among the bottom 99 percent.

The increasing concentration of income among extremely wealthy Ohioans reflects trends across the United States. Research by economist Emmanuel Saez estimates that over the past four decades, the share of income going to the top 1 percent of earners at the national level has more than doubled, from around 9 percent of the nation’s income in the mid-1970s to more than 20 percent in 2013. This sharp rise in top incomes has occurred as middle-class families across the country share the struggle of those in Ohio.

Public policy can improve—or worsen—the lives of middle-class Ohioans

The good news is that this uneven distribution of economic growth is not inevitable. The levels of inequality currently seen in Ohio and across the United States are not the natural byproducts of economic growth; rather, they are the effect of policies designed to help those at the top. While some factors contributing to the unequal distribution of earnings—such as globalization and skill-based technological change—are largely beyond the control of state policymakers, decades of conscious political choices have furthered the gap between those at the top and everyone else.

Ohio’s tax system

One prime example of policy stacked against Ohio’s middle and working classes is the state tax system. In 2013, Ohio reduced personal income tax rates by 10 percent across the board—with a 50 percent exemption for business income up to $250,000—while increasing the regressive sales tax from 5.5 percent to 5.75 percent. This followed a gradual 21 percent income tax cut that started in 2005 and completed in 2010.

Most recently, Ohio Gov. John Kasich (R) signed a budget in June 2015 that decreases income taxes by another 6.3 percent across the board, reducing the top tax rate to less than 5 percent and translating to a tax cut of more than $10,000 per year for the top 1 percent of taxpayers. Meanwhile, middle-income earners—those in the middle 60 percent—will receive an average cut of just $24, while taxes will actually increase by $20 for taxpayers in the lowest income bracket. The budget also increased the exemption on the first $250,000 of business income to 75 percent in 2015, which will increase to a full 100 percent beginning in 2016. Additionally, a committee was created to explore how to transition to a flat income tax—in which all earners pay the same tax rate—by 2018.

Ohio’s reduction of personal income taxes and its increase in sales tax effectively means that the working and middle classes will pay a higher proportion of their incomes in taxes than high-income earners. Personal income taxes are commonly the most progressive component of a state tax structure: In most states, including Ohio, their rates increase with income. Sales, excise, and property taxes, on the other hand, are generally regressive: By taxing everyone at the same rate, families that earn less end up paying a greater proportion of their income than do the wealthy.

Despite recently creating some relief for families making less than $10,000 per year with a limited, nonrefundable state Earned Income Tax Credit, the overall result of Ohio’s tax policies is that working- and middle-class earners pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than do those at the top. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, or ITEP, Ohio’s tax system results, on average, in the lowest 20 percent of income earners paying 11.7 percent in taxes, the middle 60 percent of earners paying 10.2 percent, and the top 1 percent paying just 5.5 percent.

Minimum wage

In addition to a tax system that does not disproportionately tax those at the bottom and middle, the minimum wage is an important policy for fighting inequality. Ohio has made some progress recently with a slight increase in its minimum wage. Ohio’s minimum wage has been slightly higher than the federal minimum wage since 2006, and in 2015, the state increased the minimum wage by 15 cents—from $7.95 to $8.10 per hour.

While this is a step in the right direction for workers, there is still a way to go before the state reaches the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage guaranteed by federal law in 1968: approximately $10.97 per hour in today’s dollars. By not raising the minimum wage, policymakers are not only harming the thousands of Ohioan families attempting to work their way out of poverty but also are harming those higher on the wage scale who might benefit from the spillover effects of a higher minimum wage, which would cause employers to raise the pay of workers who earn well above the minimum wage.

Collective bargaining rights

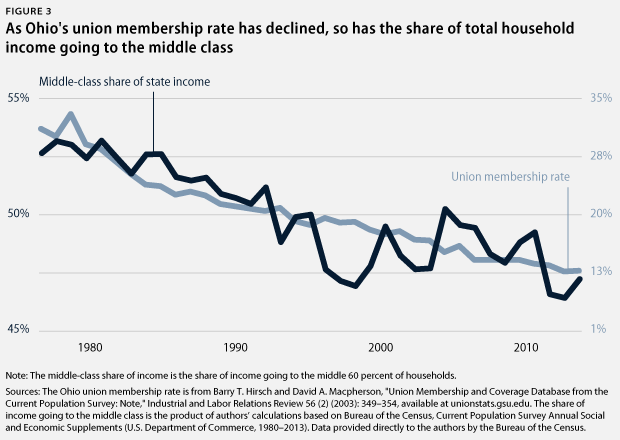

Another important yet often overlooked reason for the decline of the middle class in Ohio and throughout the United States is the weakening of unions and the erosion of collective bargaining rights. Unions advocate for middle-class interests in both the workplace and the political sphere: They encourage increased worker political participation; advocate to protect programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, that are critical for the middle class; and safeguard fair pay and essential benefits for their members. As a result, unions are essential for maintaining a thriving middle class. The gains that unions win for their own members also can help establish broader standards that benefit nonmembers as well.

Given the benefits that collective bargaining provides to workers, it is unsurprising that as the union membership rate in Ohio has declined, the share of income taken in by the middle class has declined as well. This has mirrored trends at the national level, as an ever-increasing share of the nation’s economic gains have been redistributed to those at the very top at the expense of everyone else. Indeed, research has estimated that the decline of organized labor has contributed to the growth of national inequality approximately as much as the increasing monetary returns to education, which tend to disproportionately benefit those at the very top.

Conclusion

Rebuilding the middle class in Ohio and across the United States will not be easy, but strong public policy can help the middle class return to its essential role as a driver of broad-based economic growth and promoter of economic mobility. While improving workforce education and ensuring that the returns of education are more equitably distributed is, of course, critical to strengthening the middle class, there is a range of other equally important policies. Elected officials should work to strengthen workers’ collective bargaining rights and further increase the state’s minimum wage. Several other state-level policies—such as ensuring paid family leave, boosting retirement savings, and more fairly allocating money for education—also would improve the health of the middle class in the short and long terms.

By implementing these and other reforms that directly benefit the middle class, Ohio can ensure that future economic growth actually translates into meaningful improvements in its citizens’ standard of living—something that, unfortunately, has been all too rare in the state’s recent history.

David Madland is the Managing Director of the Economic Policy team and the Director of the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Danielle Corley is a Special Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Action Fund.