Despite being constantly thrown about by politicians and pundits alike, the term “middle class” has no agreed-upon definition. But regardless of how one chooses to define it, by most measures the middle class is struggling. Over the past several decades, wages for the typical worker have been stagnant while household debt as a share of income has nearly doubled and inequality has reached near-record highs. Whether one is concerned about middle-class wages, incomes, mobility, or their relationship to the rich and the poor, one policy solution can help strengthen the middle class: strengthening unions. Unions increase workers’ wages and benefits, boost economic mobility in future generations, reduce runaway incomes at the top, raise the share of national income going to the middle class, reduce inequality, decrease poverty, and improve workers’ general well-being.

Study after study has come to the same conclusion: When workers come together in unions, they can help make things better for themselves, and indeed most Americans. Joining together enables workers to negotiate for higher wages and benefits, and when unions are strong, these benefits can spill over into other nonunion workplaces. Unions of working people also help ensure that government works for everyone—not just those at the top—by encouraging people of modest means to vote and by providing a crucial counterbalance to wealthy interest groups. Their ability to improve conditions in the workplace and in our democracy means that unions play a critical role in building the middle class.

That is why policymakers need to make strengthening worker organizations a top priority. Unfortunately, today the percentage of workers in unions is about 11 percent and less than 7 percent in the private sector, figures approaching the lows of a century ago. This decline has contributed to myriad struggles for the middle class. This issue brief reviews the research showing the many ways that strong worker organizations are necessary to strengthen and grow the middle class.

Unions increase workers’ wages

The U.S. economy has grown significantly in recent decades. However, unlike in previous eras, workers today are not receiving their fair share of the economy’s gains. Since 1973, productivity—the amount of output per worker—has grown about eight times as fast as the typical worker’s pay. While today’s workers are better educated and more productive than ever, middle-class wages are not growing appropriately to reflect this fact. Unions help workers share in the gains of a more productive economy, since workers who join together are able to negotiate on a more equal playing field with their employers.

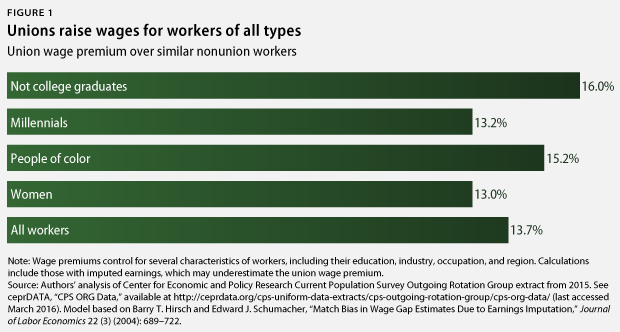

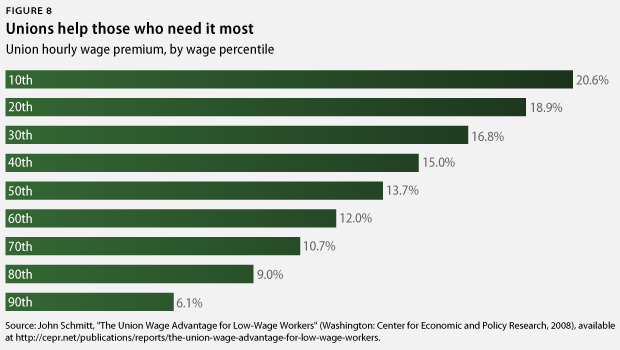

The degree to which unions increase workers’ wages is a heavily studied topic by economists. When unionized workers are compared to their similar nonunionized counterparts, analysis typically shows union wages to be 10 percent to 20 percent higher. The union wage premium is even larger for some demographic groups that, on average, receive lower pay, including workers of color and those without a college education. And these estimates may underestimate the total impact of unions on all workers’ pay due to the union “threat” effect, which occurs when union workplaces put upward pressure on wages at nonunion firms. When unions represent a significant percentage of workers in an industry, nonunion firms often raise their wages to union levels to match the standards in the industry and to discourage their workers from joining a union.

Unions increase workers’ benefits

Higher wages are not the only key to a successful middle-class life. Workers also need good benefits, such as retirement plans and high-quality health insurance. And since the number of households with two working parents has risen over the decades, family-friendly workplace policies, such as paid sick leave and family leave, are very important for the middle class. Workers in unions have the power to negotiate for these benefits and ensure they are high quality. Some examples of high-quality benefits include reasonable out-of-pocket expenses for health insurance or having more hours of paid leave. In addition, unions often help workers by making sure workers know how to access these benefits.

Data from the 2015 National Compensation Survey confirms that U.S. union workers are more likely to have these important benefits. According to the survey, 94 percent of union workers have access to retirement benefits, while only 65 percent of nonunion workers do. In addition, 85 percent of union workers are able to take paid sick leave, compared to 62 percent of those without union representation. When union benefit premiums are adjusted for other factors such as industry and occupation, union workers still bring home better benefits. For example, research has shown that union workers in the United States are 28 percent more likely to have health insurance—and pay a lower share of premiums for it—and are 54 percent more likely to have a retirement plan than nonunion workers at similar workplaces. Union women in the United States are more likely to take parental leave, which is more likely to be paid. Similarly, research from Britain shows that union workplaces are much more likely to provide parental leave and have child care facilities or subsidies.

Unions support high economic mobility

A central tenet of the American dream is that all workers, regardless of where they start, can make it into the middle class. In reality, economic mobility is lower in the United States than it is in other advanced economies. Making it easier for workers to join together in unions can provide a key pathway for increasing mobility for both union members and the general public, both by directly helping union members and by advocating for policies that benefit all working people.

Research by Harvard economist Richard Freeman, Wellesley economist Eunice Han, and David Madland and Brendan V. Duke of the Center for American Progress has shown that being in a union is associated with higher future wages for one’s children—especially for kids whose fathers do not have a college education, further boosting intergenerational mobility. Indeed, American children of non-college-educated fathers earn 28 percent more as adults if their father was in a labor union compared to children in similar families but whose father was not in a union.

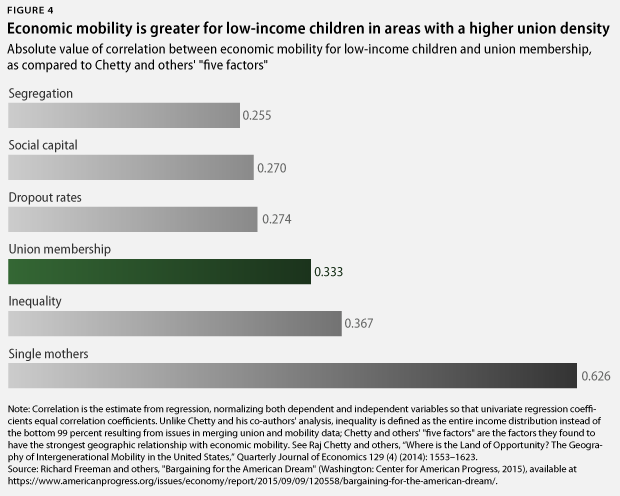

And stronger unions do not just help the children of union members. Low-income children who grow up in an area with higher union density tend to rank relatively higher in income distribution as adults than those from areas with few union members. In fact, the report’s authors found that an area’s union density is as strong a predictor of upward economic mobility for low-income children as the area’s high school dropout rate.

Unions reduce runaway incomes at the top

The richest 1 percent of Americans have captured 70 percent of the economic growth in the past 40 years, leaving the middle class behind. And with this increased concentration of income, the wealthy are able to play an outsized role in politics, shaping government policy to help themselves instead of the population at large. The combined strength of workers in unions provides a counterbalance to the power of the wealthy—both at the bargaining table and in politics.

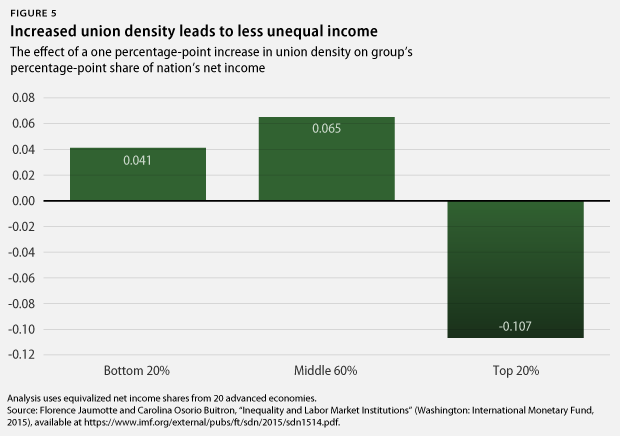

The evidence is clear: When unions are stronger, runaway incomes of the wealthiest are constrained. One study by International Monetary Fund economists found that weaker unions have led to the rich becoming richer across the globe; in fact, a 10 percentage point decrease in a country’s union density was associated with a 5 percent increase in the gross income share going to the richest 10 percent. And multiple studies have found that in companies and industries with stronger unions, CEOs are paid less.

Unions increase the middle-class share of incomes

The share of the nation’s total income that the American middle class brings home has been falling since 1968. As a result, the middle 60 percent of Americans now receive well less than half of the nation’s income—about as low a percentage as has been recorded since this data began being collected. This hollowing out of the middle class is very concerning, as a strong middle class is a key driver of economic growth through its ability to generate stable demand and perform other critical functions such as enabling entrepreneurship and promoting human capital development. Empowering more workers to negotiate together is a crucial way to restore this middle-class income share.

Research from the United States and other advanced economies clearly demonstrates that increased union density is associated with more income accruing to the middle class. As can be seen in Figure 6, there is a close correlation between the declining share of income going to the middle class and the declining percentage of workers in unions. In 1968, when unions represented 28 percent of workers, the middle class—defined as the middle 60 percent of income earners—took home 53 percent of the nation’s income. By 2014, unions represented only 11 percent of the workforce and the share of income going to the middle class had declined to 46 percent.

Similarly, a separate CAP analysis from Freeman, Han, Madland, and Duke found that falling union membership explains about one-third of the decline in the percentage of U.S. workers who are middle class from 1984 to 2014.

Unions reduce wage inequality

In recent decades, Americans’ incomes have grown further and further apart. It is clear that declining worker power, as measured by union membership, has played a key role in this development. Not surprisingly, given that unions help increase the share of income going to the middle class and constrain top-end incomes, unions help reduce wage inequality, as well.

Bruce Western of Harvard University and Jake Rosenfeld of the University of Washington found that the decline of unions from 1973 to 2007 explains up to one-third of rising wage inequality among men and one-fifth among women. Many other studies have similarly reached the conclusion that declining union strength is a key contributor to rising wage inequality.

Unions reduce poverty

Too many Americans are living in poverty and unable to reach the middle class. And many people in the middle class live through periods of poverty: Nearly 35 percent of Americans lived below the monthly poverty line for at least two months between 2009 and 2012. As a result, reducing poverty is central to the task of strengthening and growing the middle class. Unions play a key role in fighting poverty through their political influence and the increased negotiating power they bring to workers.

Among the lowest-wage workers, a union contract raises wages by approximately 21 percent. Unions’ effect on fighting poverty is not just limited to union workers, however. In studies of advanced democratic countries around the world, researchers have found that working people in highly unionized areas are less likely to live in poverty. Similarly, a study that compared U.S. states found that state-level unionization measures actually had a larger impact on working poverty rates than gross domestic product, or GDP, per capita and economic growth rates. The union effect remained after controlling for households’ union status and even dropping union households from the sample entirely, showing that unions do not just affect workers by facilitating higher-paying union contracts but also through raising nonunion wages and by taking political action.

Unions increase well-being, especially health and life satisfaction

Americans are becoming more and more isolated. Research from Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam has shown that they are less likely to join clubs, socialize with each other, or volunteer than in the past. This declining “social capital” may negatively affect health and life satisfaction. However, unions may help combat these negative effects not only through their ability to improve economic conditions but also through their ability to bring people together in support of common goals. Unions provide a kind of social capital for workers and encourage workers—especially those with lower incomes and less education—to join other organizations, especially political organizations, which can boost their sense of agency. This combination of factors may help explain why unions have a positive impact on workers’ health and general sense of well-being.

When sociologists Megan M. Reynolds and David Brady examined similar union and nonunion workers, they found that union workers were significantly more likely to report being in good health. Similarly, research from Baylor political scientist Patrick Flavin and others finds that countries with higher levels of union membership tend to have more satisfied citizens and that union members, on average, report higher life satisfaction—even when compared to nonmembers with similar demographics.

Conclusion

The number of Americans in unions has fallen precipitously in recent decades, and working Americans—whether union members or not—are paying the price. Despite the growing economy, middle-class workers are falling behind as the gains are mostly captured by those at the top. This is harmful to the country. Without a prosperous middle class to drive the economy, growth falters, society polarizes politically as trust declines, and the quality of democratic government suffers.

Unless policymakers strengthen worker voice and power, the middle class will remain at risk. Workers are better off when they have a collective voice: They earn more in the labor market and can better stand up for their interests in democracy.

Study after study confirms that stronger unions are associated with higher wages, better benefits, a stronger middle class, increased economic mobility, and reduced poverty. As policymakers strive to make the economy work for everyone, they should be sure to include policies that increase worker voice and power in their solutions.

David Madland is a Senior Fellow and the Senior Advisor to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Alex Rowell is a Research Assistant with the American Worker Project at CAP Action.