Introduction and summary

The federal government spends more than $1 trillion every year though contracts, grants, and other funding vehicles to deliver essential goods and services. It funds everything from the design and manufacture of sophisticated weapons systems to the construction of roads, bridges, and dams; from in-home care for aging Americans and those with disabilities to financial assistance programs that allow veterans and working families to access higher education. This spending creates tens of millions of jobs throughout the economy.1

American policymakers have long harnessed the power of this spending by requiring recipients to create decent jobs. Yet today, these protections cover less than half of all spending, and too often, even the jobs covered by existing protections pay poverty wages.2 Moreover, some anti-worker lawmakers are threatening to dismantle even these standards.3

Job quality standards should apply to all taxpayer-supported work regardless of whether it is financed through federal contracts, grants, loans, or even tax incentives. Policymakers who care about workers must defend existing job protections from attacks and fight to strengthen policies to ensure that all government spending creates good jobs.

Over the past century, American policymakers developed a series of protections to ensure that companies receiving federal funds pay their workers market wages, provide good benefits and equal opportunity for all workers, and allow workers to join together in unions. Federal lawmakers also enacted protections to ensure that many of the jobs created by this spending are created in the United States. As the government’s spending footprint grew, lawmakers expanded protections that originally applied only to contracted construction work to new industries and new spending vehicles.

The trouble is that today, there is an uneven patchwork of workplace standards for companies receiving government support. While workers on jobs funded through federal contracting dollars enjoy numerous wage and benefit protections, these policies usually do not apply to jobs funded through federal grants, loans, loan guarantees, and tax incentives. Moreover, existing policies are too weak, allowing companies receiving contracts to fight vehemently against workers’ efforts to form unions and, too often, to pay them far below a living wage. And while the United States has numerous policies to promote contracting in ways that create American jobs, standards designed to ensure that the federal government purchases American-made products are too often poorly enforced and cover a limited number of spending programs as well as a limited number of end products.

Worse, the Trump administration and some Republicans in Congress are acting to dismantle job quality protections for taxpayer-funded jobs. President Donald Trump has already signed legislation eliminating protections for contracted workers.4 Moreover, anti-worker lawmakers have introduced legislation to weaken and even repeal prevailing-wage laws.5 Pro-worker lawmakers should fight against all efforts to destroy standards for workers.

Beyond these imminent battles, lawmakers should embrace a bold vision to ensure that all government spending—including federal contracts, grants, loans, loan guarantee programs, and tax incentives—creates good jobs and provides new tools to build power and voice for working Americans. The text box below lists all standards that should be guaranteed for jobs funded through federal spending.

Essential job standards for taxpayer-supported work

Wages:

- Coverage under the McNamara-O’Hara Service Contract Act and the Davis-Bacon Act prevailing-wage standards

- Minimum wage of $15 per hour so that no federally supported jobs pay poverty wages

Benefits:

- Health and welfare benefits, or cash equivalents, as required under federal prevailing laws6

- At least seven days of paid sick leave

Protections:

- Refrain from discrimination and retaliation on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, or veteran status

- Respect workers’ right to join a union and bargain collectively

- Comply with existing workplace laws and require transparency on compliance record

- Commit, when possible, to using goods and services produced in the United States

Congress will have opportunities to implement these protections. President Trump promised $1 trillion investment in infrastructure and will soon announce a more detailed infrastructure plan.7 While Trump thus far has failed to commit to including wage protections on all jobs created through the package, lawmakers who support workers should ensure that any infrastructure package creates good jobs for all taxpayer-supported work, including all work funded by public-private partnerships.

Raising standards in this way will not only help working people but will also ensure that businesses that respect their workers can compete on an even playing field—and ensure that taxpayers get a good value for their investment. After Maryland implemented a contractor wage standard, for example, the average number of bids from companies for state contracts increased nearly 30 percent.8 Nearly half of contractors said that the new standards encouraged them to bid because they leveled the playing field.

In order to build support for these policies, this report provides a history of American policies to ensure that government spending creates good jobs; an explanation of the problems with the current system; policy recommendations; and evidence showing that high standards benefit workers, business, and taxpayers.

To be sure, enacting these policies at the federal level will be difficult. However, by fighting to ensure that these standards are attached to all jobs created through an infrastructure package, and by opposing efforts to weaken standards, policymakers can show they are serious about ensuring that working families can access decent jobs that pay middle-class wages, as well as demonstrate that they understand the magnitude of problems facing working Americans.

History of American policies to raise standards on taxpayer-funded jobs

American policymakers have long taken the stance that when government supports private-sector jobs, it should function “as a model employer to be emulated by the private sector.”9 Throughout the past century, policymakers instituted laws to ensure that companies receiving government support provide workers decent wages and benefits, are safe and free from discrimination, and give their employees a fair shot at coming together in unions.

While most existing standards are aimed only at jobs created through federal contract spending, in specific instances, the federal government has also adopted policies to raise standards for jobs funded through other types of federally assisted financial support.

Standards for contracted workers

Progressive Republican lawmakers in Kansas enacted the first reform in the United States to raise standards for taxpayer-supported workers in 1891, with legislation requiring that construction workers on projects financed through state spending be paid a market wage. The state government instituted the law as part of a series of economic reforms—including child labor laws, compulsory schooling, the eight-hour day, and convict labor laws—in order to combat falling wages in the state and encourage business to compete on the basis of acquiring a highly skilled workforce rather than low labor costs.10

These standards provided the foundation for federal reforms first initiated at the outset of World War I and then throughout the Great Depression.

Secretary of War Newton Baker established a “board of control” in 1917 in order to improve working conditions and garner labor peace from garment workers sewing Army uniforms. At its creation, Baker warned, “The government cannot permit its work to be done under sweatshop conditions, and it cannot allow the evils widely complained of to go uncorrected.”11

The tripartite body—which included a government official, an industry representative, and a worker advocate—was permitted “to enforce the maintenance of sound industrial and sanitary conditions in the manufacture of army clothing, to inspect factories, to see that proper standards are established on government work, to pass upon the industrial standards maintained by bidders in army clothing, and act so that just conditions prevail.”12

While this intervention was constrained to industry-specific war efforts, New Deal reformers a generation later would implement wage standards applicable to a much larger portion of the contracted workforce. When Congress enacted the Davis-Bacon Act in 1931—which provided that federally contracted construction workers would be paid a “prevailing” or market wage—the federal government stated its intention to use government contracting to help workers and uphold fair competition for companies that paid decent wages. According to the Congressional Research Service, “Congress sought to end the wage-based competition from the fly-by-night operators, to stabilize the local contracting community, and to protect workers from unfair exploitation. Employers could compete on the basis of efficiency, skill, or any other factor except wages.”13

Five years later, in 1936, with the passage of the Walsh-Healey Act, prevailing-wage protections were extended to contractors manufacturing goods for the federal government.

But perhaps the most aggressive use of federal contracting to raise standards for workers came during World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt created the National War Labor Board and the War Production Board to protect the rights of contracted workers to form unions and ensure that labor unrest did not disrupt war production. In exchange for a pledge not to strike, the government established policies to encourage organizing in both war industries and companies producing civilian goods, to prevent companies engaging in labor law violations from receiving federal contracts, and to support workers’ ability to advocate openly for unions on factory floors.14

In addition, Roosevelt created the Fair Employment Practices Commission, which outlawed discrimination in defense industries.15 Companies who openly acknowledged whites-only employment policies were told that they must integrate or lose their war contracts.16

While many of these interventions lapsed during peace time, by the war’s end, regional and racial wage differentials had significantly narrowed, unionization rates had soared, and benefits such as vacation and sick leave had become commonplace.17 In 1964, Congress amended the Davis-Bacon Act to include fringe benefits in the determination of prevailing wages.18

Moreover, policies to ensure that government spending created good jobs increasingly enjoyed bipartisan support. When Congress enacted the Service Contract Act to extend prevailing-wage law to employees of contractors furnishing services to or performing maintenance for federal agencies, the idea that taxpayer-supported jobs should promote decent wages was broadly accepted. The bill passed the Senate in 1965 “virtually without discussion,” according to the Congressional Research Service.19

Lawmakers emphasized the government’s moral obligations as an employer and that government purchasing can drive wages even lower. Solicitor of Labor Charles Donahue argued, “The employees who would be covered by the proposed legislation are among the most poorly paid and the economically deprived in our society.”20

Moreover, the government was in many cases the largest buyer by far in the marketplace and thereby had the power to set the market rate for goods, services, and labor. The danger thus existed that the government could lower wage standards for nonfederal contract workers below that which would be paid by the market.

Finally, policymakers recognized that low wages could be bad for taxpayers and the economy. The labor solicitor argued that it is “doubtful whether the Government gains in the long run by a policy which encourages the payment of wages at or below the subsistence level.”21

He believed that “[s]ubstandard wages must inevitably lead to substandard performance. Further, the economy as a whole suffers from the reduced purchasing power of workers. The present policy of low bid contract awards is one under which everyone loses—the employee, the Government, the responsible contractor—that is, everyone except the fly-by-night operator who is eager to profit from the under compensated toil of his workers.”22

When President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Service Contract Act into law, government support for service jobs in the private sector was just beginning to grow—with assistance flowing primarily through contracting. Johnson’s intent was to fill the one final hole in federal prevailing-wage laws. He stated, “This legislation … closes the last big gap in protecting those standards where employees of contractors are doing business with the Federal Government.”23

That same year, President Johnson signed Executive Order 11246 to prevent discrimination among contractors on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin.24 The order applied not only to the positions directly funded through federal spending but also to all employees of companies with federal contracts regardless of whether their work was funded through procurement spending. The order also allowed for the creation of an enforcement body, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP), whose mission was later expanded to include enforcing protections for workers and preventing discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability, and status as a protected veteran. Research shows that through its power to withhold future contracts, the OFCCP significantly increased equal opportunity for women and people of color in companies receiving federal contracts.25

In the intervening years, American presidents have continued to use their executive authority to raise standards for contracted workers.26 For example, President Richard Nixon signed Executive Order 11598 to require government contractors and subcontractors to take steps to advertise and provide job opportunities to veterans, and President Bill Clinton penned Executive Order 12933 to require successor service contractors to provide a right of first refusal to workers employed on the previous contract.27

Most recently, in the face of congressional inaction to raise the federal minimum wage and enact stronger protections for all working Americans, President Obama signed a series of executive orders to ensure that employees of federal contractors have access to decent jobs, including actions to raise the minimum wage for contracted workers to $10.10 per hour; ensure that workers receive at least seven days of paid sick leave; protect LGBT workers from discrimination on the job; help ensure that companies respect their workers’ right to organize unions on the job; and require companies to comply with existing workplace laws before they receive new contracts.28

Standards on other types of government spending

While jobs created through the federal procurement system enjoy the most extensive protections, in specific instances, the federal government has also adopted policies to raise standards for jobs funded through grants, loans, loan guarantees, and even tax incentive programs.

For example, some federal financial assistance programs carry job quality standards separate and apart from federal contracting standards. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 gives the federal government the authority to ensure that recipients of federal financial assistance—which includes grants, loans, and leases of federal lands, but not contracts—do not discriminate against program beneficiaries.29 Likewise, the Head Start Act prohibits federal assistance from being used to “assist, promote or deter union organizing.”30

In other cases, federal procurement standards have been extended to other types of financial funding. For example, when President Obama took action to raise the minimum wage for contract workers and to create a sick leave requirement, he also extended coverage to “contract-like instruments,” which include workers at companies providing concessions in federal buildings and lands.31

Most notably, Congress has regularly extended construction wage and benefits standards for contracted companies to other types of financial assistance. Since enactment of the Davis-Bacon Act in 1931, Congress has frequently enacted “Related Acts,” which attach prevailing-wage standards for construction work across a variety of types of spending programs, including grants, loans, loan guarantees, mortgage insurance, and tax incentive programs.

While this is a piecemeal approach—rather than a consistent presumption that new grant, loan, and tax incentive programs will include prevailing-wage protections—Congress has enacted approximately 60 related acts.32 Frequently, these standards are applied to government-supported transportation and infrastructure projects, but these standards have also been extended to the construction of housing, hospitals, and veterans’ homes; arts projects; and wastewater treatment facilities. The text box below provides a sampling of the types of programs to which Davis-Bacon provisions apply.

In recent years, policies to extend Davis-Bacon standards to new federal spending programs have been opposed by a number of anti-worker lawmakers but still managed to win support in Congress. While the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 was enacted with little support from congressional Republicans, the law provided Davis-Bacon prevailing-wage coverage for projects funded through tax incentive programs, as well as grants, loans, guarantees, and insurance.33 Other types of innovative funding structures—such as public-private partnerships to fund major transportation projects—are often covered by federal Davis-Bacon standards.34

These requirements often are attached to funding that flows first to a state or local government before reaching private-sector actors. For example, transportation loans and loan guarantees are made available to state and local governments, transit agencies, railroad companies, or other private companies under the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) programs. State and local agencies then use the federal monies to fund private-sector companies completing the work. Any project that receives even a dollar of TIFIA funds must comply with Davis-Bacon wage and benefits provisions on their labor contracts.35

Davis-Bacon wage and benefit standards extend to grants, loans, loan guarantees, and innovative financing mechanisms

Grants:

- Federal-Aid Highway Act and the Surface Transportation Assistance Act: Financial aid to states for highway construction – 23 U.S.C. § 113(a)

- General Education Provisions Act: Construction under assistance programs run by the Department of Education – 20 U.S.C. § 1232b

- National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act: Grants for projects in the arts and for the promotion of progress and scholarship in the humanities – 20 U.S.C. § 954(n); § 956(j)

- Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act: Block grants for affordable Indian housing and facilities – 25 U.S.C. § 4114(b)

- Clean Water Act: Grants to construct publicly owned waste treatment works – 33 U.S.C. § 1372

- State Veterans’ Home Assistance Improvement Act: Assistance to states for constructing and remodeling existing facilities – 38 U.S.C. § 8135(a)(8)

- Postal Reorganization Act: Lease agreements for the U.S. Postal Service for space greater than 6,500 square feet – 39 U.S.C. § 410(d)

- Hospital Survey and Construction Act: Grants for construction or modernization of public or nonprofit private medical facilities – 42 U.S.C. § 291e(a)(5)

Loans and loan guarantees:

- Urban Mass Transportation Act: Grants and loans for rail mass transit – 49 U.S.C. § 5333(a)

- Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act: Loans and loan guarantees for railroad improvements – 45 U.S.C. § 822(h)(3)(A)

- National Housing Act: Federal Housing Administration nonsingle family mortgage insurance – 12 U.S.C. § 1715c

- Wolf Trap Farm Park Act: Grants and loans for reconstruction of the Filene Center at Wolf Trap Farm Park – 16 U.S.C. § 284c(c)

Innovative financing mechanisms:

- Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act: Provides credit assistance in the form of direct loans, loan guarantees, and standby lines of credit to projects of national and regional significance to qualified public or private borrowers, including public-private partnerships, private firms, and transportation improvement districts – 23 U.S.C. § 601-609

- American Recovery and Reinvestment Act: Projects financed with proceeds of certain tax-favored bonds, including New Clean Renewable Energy Bonds (New CREBs); Qualified Energy Conservation Bonds (QECBs); Qualified Zone Academy Bonds; Qualified School Construction Bonds; and Recovery Zone Economic Development Bonds – §1601 ARRA Division B, 123 Stat. 36136

Yet today, prevailing-wage standards and other protections are under significant existential threat. President Trump is already unraveling job standards for contracted work that were instituted under President Obama, and anti-worker legislators have introduced several bills to weaken and even eliminate Davis-Bacon protections.37 Moreover, conservative groups are increasingly pushing Congress to attach language that weakens Davis-Bacon protections to must-pass legislation. For example, Rep. Paul Gosar (R-AZ) introduced an amendment to the 2018 National Defense Authorization Act that would have reduced prevailing wages on federally funded construction projects.38 While these actions have not yet been successful at the federal level, corporate lobby groups are increasingly motivated in this fight and have helped repeal at least four state-level prevailing-wage laws since 2015.39

Taken together, these actions could eliminate job protections that have been developed for taxpayer-funded work over the past century and result in significantly lower wages for American workers on federal projects.

Problems with the current system

While the Trump administration and anti-worker lawmakers in Congress represent an immediate threat to existing federal job standards on taxpayer-supported work, the current system is far from perfect. Workers on jobs funded through federal contracting dollars enjoy numerous wage and benefit protections, but these policies frequently do not apply to workers on jobs funded through other spending programs. As a result, existing job standards cover less than half of all government spending on contracts, grants, loans, and tax incentives. In addition, existing job quality standards too often pay very low wages, do not protect workers attempting to form a union from employer opposition, and leave workers with little power to negotiate for better wages and benefits.

Job standards cover less than half of all private-sector spending

As discussed above, American policymakers have frequently attached job quality standards to funds awarded through the federal contracting system. Yet the federal government funds a massive workforce through other types of spending vehicles, including grants, loans, loan guarantees, and even tax incentives—jobs which are largely free from any sort of government protections. In fiscal year 2016, the federal government awarded about $474 billion on federal contracts, but it spent more than $668 billion on grants; awarded $2.4 billion in direct loans, and made available even larger sums of private capital through loan guarantees and tax incentives.40

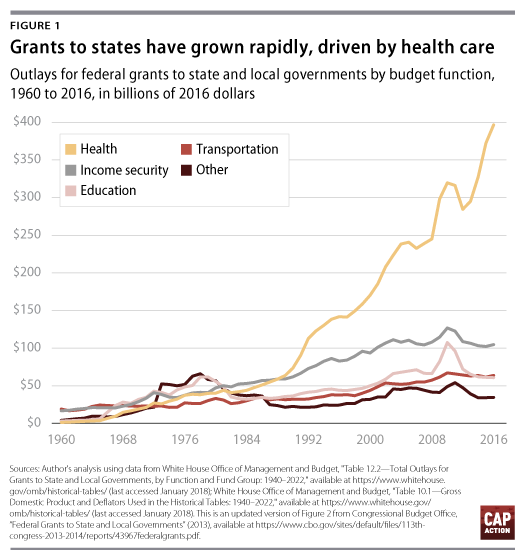

This spending has increased significantly in the past 60 years, particularly in service-sector work. Spending on federal grants alone grew tenfold between 1960 and 2011—or twice as fast as real gross domestic product growth, according to John DiIulio at the University of Pennsylvania.41 This was largely driven by increases in health care spending as the government expanded spending on Great Society programs to provide care to low-income Americans.42 For example, the Congressional Budget Office found that while federal grants to state and local governments for transportation projects remained relatively flat, grants for health care programs—including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program—increased by seven times between 1980 and 2011.43

While Congress has regularly extended Davis-Bacon protections on transportation and infrastructure funding, it has not taken parallel action to extend the Service Contract Act or other types of job protections to nonprocurement spending.44 And even when Davis-Bacon standards apply to construction work, ongoing work associated with a project may not be covered. For example, public-private partnerships are typically structured so that maintenance and operations jobs are not covered by any sort of wage standards.45 As a result, millions of other federally supported service-sector jobs are not covered by wage and benefit standards.

The federal government does not collect comprehensive data on the total number of jobs supported by taxpayer dollars. However, the progressive think tank Demos estimates that the federal government extends prevailing-wage standards to about 276,000 workers annually working on federal construction grants. But looking only at a subset of federal spending programs in the service sector, Demos estimates that nearly 10 million workers are employed in taxpayer-supported jobs that do not receive prevailing-wage protections.46

By far, the largest group in its research included 8.9 million workers employed in health care industries, where government spending alone accounted for at least 20 percent of industry revenue in 2013.47 This estimate included both in-home health care and nursing and residential care, which the report found had median wages of $11.93 and $12.56, respectively. The report also surfaced 787,000 jobs supported by Small Business Administration loan guarantees, National School Lunch Program state grants, and federal concessions contracts.48

Wage standards set at poverty level

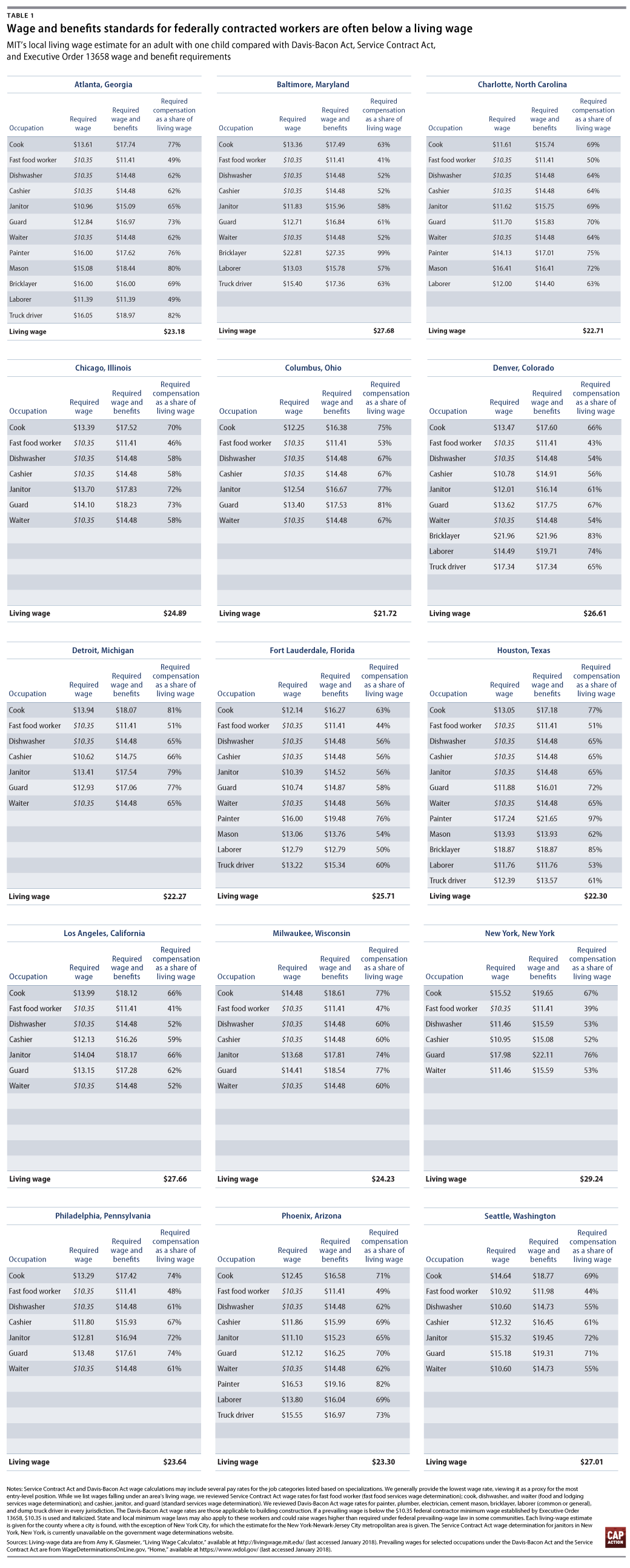

Prevailing-wage laws can be an important force for ensuring that federal contracts do not drive down wage standards; however, these wages vary locally, and in some cases, prevailing wages are very low. President Obama helped boost the wages of contracted workers in 2014 by signing Executive Order 13658, which raised the minimum wage for all contracted workers to $10.10 and indexed it to inflation. Today, the contractor minimum wage is $10.35 per hour. While the order raised the wages of an estimated 200,000 workers, all too often, workers’ wages fall below a living wage.49

As the tables below demonstrate, prevailing wages for a range of jobs across the country fall below a living wage needed to sustain a family with one child. We use the living wage estimates developed by Amy Glasmeier at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.50

In addition, the way that prevailing wages are calculated can have a direct impact on the strength of wage standards. For example, Davis-Bacon prevailing wages previously could be set at the wage paid to 30 percent of workers in an industry in that locality.51 This helped raise wages for all workers by ensuring that the collectively bargained wage was the prevailing wage in areas of high union density. The Reagan administration increased the threshold to 50 percent, which resulted in the government paying lower wages to construction workers on federal projects.52

Workers cannot form unions

During the former administration, President Obama signed several executive orders to ensure that companies receiving federal contracts respect their employees’ right to organize into unions. These policies require that contractors post notices informing employees of their right to bargain collectively; require successor service contractors to provide a right of first refusal to workers employed on the previous contract; encourage federal agencies to enter into project labor agreements on large construction projects; and prevent companies from using federal funds to fight the efforts of workers to form a union.53

Yet it is still far too easy for anti-union companies to fight workers’ efforts to join together in unions and negotiate for better pay and benefits. While existing government policies prohibit companies from using federal funds to fight workers’ efforts to form unions, they are free to use their own funds to do so.

Indeed, employers typically engage in sophisticated campaigns to prevent workers from forming unions, which can include forcing workers to attend anti-union meetings—including one-on-one conversations with supervisors—and pressuring workers to reveal their private preferences for the union.54 When anti-union employers break the law, penalties are weak and insufficient. Workers are illegally fired in about one-quarter of union organizing campaigns, but they can at best hope to recover their lost wages and get reinstated in their jobs, often after years of legal battles.55

This unequal distribution of power harms middle-class Americans throughout the economy—not just those seeking to come together in unions. Numerous studies show that by forming unions, workers can negotiate for higher wages and benefits.56 Looking specifically at contracting, they also help ensure that prevailing wage laws are properly administered and enforced.57 Moreover, when unions are strong, higher wages and benefits can spill over into other nonunion workplaces.58 Finally, research shows that unions help ensure that government works for everyone—not just the wealthy few—by encouraging working people to vote and by providing a unique counterbalance to wealthy interest groups on economic issues.59 For these reasons, policymakers should make strengthening worker organizations—as well as raising wages for taxpayer-funded work—a top priority.

Policy recommendations

All companies receiving financial support from the federal government should be required to pay decent wages, provide good benefits, refrain from discrimination, comply with workplace laws, and respect workers’ rights to join a union and bargain collectively.

Pro-worker lawmakers should fight against efforts to weaken standards for workers on federally supported projects and should oppose any major infrastructure proposal that does not create good jobs.

Beyond these imminent battles, lawmakers should advocate for new government policies to ensure that all government spending—including federal contracts, grants, loans, and loan guarantee programs—create good jobs and provide new tools to build power and voice for working Americans.

Fight against efforts to weaken job standards

President Trump and anti-worker lawmakers in Congress have begun to chip away at standards to ensure that companies receiving taxpayer support provide good jobs. Despite evidence that about one-third of the companies that have the worst wage and safety violations continue to receive federal contracts with no safeguards to ensure future compliance with the law,60 Trump signed legislation in March to dismantle protections that would have required companies that apply for federal contracts to report on their record of compliance with workplace laws and to come into compliance if they have a poor track record.61

Unfortunately, this may be the first in a series of legislative and administrative efforts to weaken job standards for taxpayer-funded work: Last year, news sources reported that the administration was evaluating rule changes that would lower wages for contracted workers.62 And anti-worker lawmakers in Congress may advance legislation to eliminate prevailing-wage laws or lower the wages paid through the laws.63

In recent years, anti-worker lawmakers implemented a number of these measures at the state level as they also advanced legislation to weaken workers’ ability to organize into unions. Efforts to repeal prevailing-wage laws advanced at the same time as states were enacting right-to-work laws, measures that weakened protections for public-sector workers, and laws pre-empting cities from enacting wage standards.64 If anti-worker lawmakers are now successful at the federal level, American workers on federally supported projects will earn significantly lower wages, have fewer protections, and have less power on the job.

Policymakers who care about workers must remain united in their opposition to every effort by the president and anti-worker lawmakers to weaken standards for workers on federally supported projects.

Expand job protections for taxpayer-funded work

Pro-worker lawmakers should also advocate for policies to require that all government spending creates good jobs. This will require expanding wage, benefits, and discrimination protections that currently apply primarily to jobs funded through federal procurement to grants, loans, loan guarantees, and tax expenditures. In addition, policymakers should strengthen minimum wage standards, protections for workers seeking to join together in unions, and Buy America and Buy American protections.

Policymakers and advocates are increasingly focused on expanding levers to ensure that taxpayer spending creates good jobs. For example, Good Jobs Nation—an organization representing federal contract workers—has called for executive action to provide contracting preferences for companies that pay living wages and to ensure that companies that do business with the federal government respect workers’ right to bargain.65 And Senate Democrats’ “Better Deal” plan recommends reforms to ensure that federal financial support programs—including contracts, grants, loans, loan guarantees, and tax breaks—include “conditions requiring companies to affirmatively notify workers of their rights and refrain from activity aimed at interfering with workers’ [ability] to join a union and bargain collectively.”66

The Center for American Progress has already called on wage and benefits protections to be included in a federal infrastructure package.67 While President Trump promised a $1 trillion investment in infrastructure and noted at a speech before North America’s Building Trades Unions that real wages for construction workers have fallen 15 percent since the 1970s,68 thus far, he has not committed to including wage protections on all jobs created through the spending.69 Moreover, the Trump administration has signaled that it may structure the infrastructure investment in a way that is less likely to include even prevailing-wage standards—by relying on public-private partnerships funded through tax breaks.70 Lawmakers who care about workers should ensure that any infrastructure package creates good jobs for all taxpayer-supported work.

More broadly, the government should take steps to ensure that job quality standards are attached to existing and new spending programs.

The federal government has regularly acted to extend Davis-Bacon Act prevailing-wage requirements to construction jobs funded through grants, loans, loan guarantees, and even some types of tax credits. Yet despite skyrocketing federal spending to support service-sector jobs, the wage protections enumerated under the Service Contract Act have never been extended beyond contracting in the more than 50 years since the law was enacted.

Job quality standards should apply to grants, loans, loan guarantees, and tax expenditures when the work occurs within the United States and its territories, the federal government is a significant market actor, and the principle purpose of the work is to construct or maintain American infrastructure or to furnish services through the use of service employees. As is the case with existing protections for the contracted workforce, job quality standards would also flow down to the workforce of subcontractors.

This would include any jobs created by a major federal infrastructure bill, including ongoing service and maintenance jobs that result from the federal funding; federal health care assistance such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and TRICARE; school nutrition assistance including the National School Lunch and Breakfast programs; federal financial aid loan and grant programs including Pell Grants, Direct Subsidized Loans, and Perkins Loans; and early childhood programs such as Head Start and Child Care Development Block Grants. However, it would exclude programs such as Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, where the primary purpose of the program is to allow Americans to purchase food, rather than providing services.

In addition, the administration must evaluate whether other financial assistance programs should be covered by these requirements. When a new financial assistance program is created to support infrastructure investments or provision of private-sector services, there would be a presumption of coverage under job standard requirements unless an agency can provide a compelling reason for exclusion. Extending these protections to contracts, grants, loans, loan guarantees, and tax expenditures that directly and fully fund private-sector jobs would be relatively straightforward. More extensive rulemaking and evaluation may be required for programs that flow through state governments and need additional support.

Specifically, companies receiving federal financial assistance should:

- Pay nonpoverty wages: Prevailing wage laws, such as the Davis-Bacon Act and the Service Contract Act, ensure that federal spending does not drive down standards, as well as help support good middle-class jobs in areas where unions are strong. Yet in too many communities, the prevailing wage is still poverty-level. A $15-per-hour minimum wage would ensure that hard work pays and would build on President Obama’s Executive Order 13658, which raised the minimum wage for federal contractors to $10.10 per hour. Companies receiving taxpayer support should be required to pay the prevailing wage or a $15 minimum wage, whichever is higher.

Moreover, prevailing-wage calculations should be strengthened to foster high industry standards. For example, policymakers can follow the lead of a number of cities and states, such as New York, Maryland, and Jersey City, New Jersey,71 that have adopted policies to help ensure that collectively bargained wage rates are also the prevailing-wage rates. They can do so by setting the wage that prevails under both Davis-Bacon and the Service Contract Act to the wage paid to 30 percent of workers in an industry in that locality.

- Provide decent benefits: These should include health and welfare benefits required by existing prevailing-wage laws72 and at least seven days of paid sick leave, as provided in President Obama’s Executive Order 13706.

- Refrain from discrimination or retaliation against employees or applicants because of their race, color, gender, religion, national origin, sexual orientation or gender identity, disability, or veteran status.73

- Respect workers’ rights to join a union and bargain collectively: Existing policies require that contract recipients post notices informing employees of their right to bargain collectively; require successor service contractors to provide a right of first refusal for workers employed on the previous contract; encourage government agencies to use project labor agreements on large construction projects; and prevent companies from using federal funds to fight the efforts of workers to form a union.74 These protections should apply broadly to federal financial assistance programs.

- Not persuade workers in union selection processes: Even when workers are covered by existing federal protections, it is still far too easy for anti-union companies to fight workers’ efforts to join together in unions and negotiate for better pay and benefits. To ensure that workers who want to form a union have a fair shot at doing so, companies should be prohibited from attempting to persuade workers employed on taxpayer-supported work to exercise or not to exercise the right to organize and bargain collectively.

- Comply with existing workplace laws: Require companies that apply for federal contracts to report on their record of compliance with workplace wage, safety, and discrimination laws and, if they have poor track record, come into compliance before they are able to receive federal contracts.75

- Create jobs in the United States: Standards designed to ensure that the federal government purchases American-made products are too often poorly enforced and cover a limited number of spending programs as well as a limited number of end products.76 Looking only at contracting, for example, the U.S. government opens a far greater share of its procurement to foreign goods than do its largest foreign trade partners covered under the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Government Procurement.77 President Trump has called for a review of current agency procedures governing Buy American and Buy America policies.78 To strengthen the monitoring and enforcement of existing standards, this effort must ensure that all federal agencies provide clear domestic content definitions and guarantee transparent and thorough audit processes.79

However, these actions will not go far enough to correct this imbalance. In addition, the federal government should establish high thresholds for granting waivers of content requirements; ensure that low-bid contracting procedures do not undercut the ability to source domestically produced content; ensure that all protected goods listed in trade agreements are also covered under Buy American protections; expand the coverage of Buy American and Buy America preferences to other types of federal spending programs, such as aid programs for water works infrastructure; and, when practicable, add key industries to protected trade lists.80

Finally, the portion of a company’s employees covered by a specific provision would vary. Wage, benefit, and union neutrality requirements would apply to all workers performing work on or in connection with a covered assistance program, as is currently the case for federal contractors covered by existing minimum wage requirements.81 Existing discrimination protections for contracted workers are much broader—covering a beneficiary’s entire workforce. Anti-discrimination requirements on other types of assistance should also cover a company’s entire workforce. Likewise, companies should be required to report on their full record of compliance with workplace laws—not just compliance with laws on work funded with taxpayer support.

Evidence these policies would raise standards for workers, taxpayers, and business owners

By implementing these reforms, policymakers would not only raise standards for working people, but, as research on the effects of contracting job standards demonstrates, also ensure that businesses that respect their workers can compete on an even playing field and provide taxpayers good value for their investment.

Good for workers

Millions of American workers would benefit from provisions to raise job standards on federally contracted work. While the federal government does not collect wage data on federally supported jobs, one recent study estimates that more than 2 million workers in jobs supported by federal contracting, Medicare spending, and other federal funds are paid less than $12 per hour.82

Existing evidence on wage standard laws demonstrates that these laws reduce poverty and ensure that workers are not paid below-market wages. From 2004 to 2013, for example, construction workers in states with strong or average prevailing-wage laws made nearly $12,000 more per year, on average, than construction workers in states with weak or no prevailing-wage laws, after adjusting for both inflation and regional price differentials.83 Research also shows that these laws ensure that companies do a better job of sharing profits with their workers and thereby can reduce inequality within effected industries, as well as help targeted communities—such as veterans—access good jobs.84

Moreover, prevailing-wage laws—which include lower pay rates for trainees—have been effective in attracting more workers of color into skilled union construction work. While nonunion companies can also provide apprenticeship opportunities, construction apprenticeships are largely concentrated in union shops. For example, in Ohio, 94 percent of female apprentices and 88 percent of apprentices of color are enrolled in union training programs, which also have a completion rate 21 percent higher than nonunion programs.85

Indeed, a new study of New York City’s construction sector by the Economic Policy Institute finds that today, black workers account for a larger share of the union construction workforce than the nonunion construction workforce, and black union construction workers earn far more—36 percent more—than black nonunion construction workers.86

Similarly, efforts to reduce workplace discrimination through federal procurement programs have been shown to be successful. After President Johnson signed Executive Order 11246 in 1965, studies show that demand for African Americans and women increased significantly in contractor establishments compared with noncontractor establishments—an 11 percent increase for black women, a 6 percent increase for black men, a 12 percent increase for other men of color, and a 3 percent increase for white women.87

While the federal government has been slow to extend many job standards to jobs funded though nonprocurement spending, state and local governments are increasingly expanding wage standards beyond contracting to other types of spending, including economic development spending, contracts for vendors, and requirements on heavily regulated industries.

Good for businesses

When governments adopt job standards, it is not only good for workers but can also provide better results for businesses. Research shows that as employees’ wages increase, so does their morale, which in turn is associated with a decrease in absenteeism and turnover, along with an increase in productivity.88 Paid sick leave also boosts economic efficiency, as workers are more likely to stay home when sick—and thereby prevent the spread of illness—and seek preventive care.89 Finally, by fostering diversity and fighting discrimination, employers can improve job commitment and relationships with co-workers, as well as increase productivity.90

For example, after San Francisco International Airport adopted a wage standard, annual turnover among security screeners fell from nearly 95 percent to 19 percent—saving employers thousands of dollars per employee per year in restaffing costs.91

Indeed, without strong standards, companies that provide good jobs choose too often not to participate in federal programs or are forced to compete against low-road companies that harm their workers by paying below-market wages, providing poor benefits, or reducing costs by committing wage theft or cutting corners in workplace safety. After the District of Columbia enacted legislation to help ensure that only companies that comply with workplace laws are able to receive government contracts, Allen Sander, while serving as chief operating officer of Olympus Building Services Inc., explained:

Too often, we are forced to compete against companies that lower costs by short-changing their workers out of wages that are legally owed to them. The District of Columbia’s contractor responsibility requirements haven’t made the contracting review process too burdensome. And now we are more likely to bid on contracts because we know that we are not at a competitive disadvantage against law-breaking companies.92

Good for taxpayers

Finally, by raising workplace standards among government contractors, state and local governments can ensure that taxpayers receive a good value.

When workers are poorly compensated or do not receive all of the wages that they earn, taxpayers often bear hidden costs by providing services to supplement workers’ incomes, such as Medicaid, Earned Income Tax Credits, and nutrition assistance. Research shows that construction workers in states without prevailing-wage laws are more likely to live in poverty, rely on government assistance programs and public housing, and lack health insurance than construction workers in states with prevailing-wage laws.93 For example, a recent study looking at the impact of prevailing-wage laws in nine states found that the 16.4 percent of construction workers in states with no or weak prevailing-wage laws receive Earned Income Tax Credits, compared with 11.3 percent in states with average or strong prevailing-wage laws.94

Moreover, several studies have found that when contractors shortchange their workers, they often deliver a poor-quality product to taxpayers. A 2003 survey of New York City construction contractors by New York’s Fiscal Policy Institute found that contractors with workplace law violations were more than five times as likely to have a low performance rating than contractors with no workplace law violations.95

A 2013 report from the Center for American Progress Action Fund found that one in four companies that committed the worst workplace law violations and received federal contracts later had significant performance problems ranging from “contractors submitting fraudulent billing statements to the federal government; to cost overruns, performance problems, and schedule delays during the development of major weapons systems that cost taxpayers billions of dollars; to contractors falsifying firearms safety test results for federal courthouse security guards; to an oil rig explosion that spilled millions of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico.”96

Finally, promoting higher standards helps ensure that taxpayers receive a good value by encouraging more companies to bid on projects, as companies that create good jobs no longer have to compete against low-road firms willing to pay poverty wages and provide few benefits. For example, after Maryland implemented a contractor living standard, the average number of bids for contracts in the state increased 27 percent—from 3.7 bidders to 4.7 bidders per contract. Nearly half of contracting companies interviewed by the state of Maryland said that the new standards encouraged them to bid on contracts “because it levels the playing field.”97

Conclusion

Every year, the federal government pays private-sector companies hundreds of billions of dollars to deliver essential public goods and services. By attaching job quality standards to all of this assistance, policymakers can raise standards for millions of workers and help create the kind of economy that all Americans want—an economy that supports high-wage job growth; ensures that businesses that respect their workers can compete on an even playing field; and makes sure that taxpayers get good value for their investment. Moreover, by granting workers more stability and more power in the workplace, policymakers can ensure that workers will be better able to advocate for themselves in our democracy and provide a more effective counterbalance against wealthy special interests.

Indeed, these are the goals and values that motivated American policymakers more than 100 years ago to first innovate by attaching job quality standards to contracted construction work. By harkening back to these goals today, lawmakers who care about working people can create a bold vision that is needed to push back against attacks on existing job standards and build wide-ranging support for the expansion of these programs.

About the author

Karla Walter is Director of the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Walter focuses primarily on improving the economic security of American workers by increasing workers’ wages and benefits, promoting workplace protections, and advancing workers’ rights at work. Prior to joining CAP Action, Walter worked at Good Jobs First, providing support to officials, policy research organizations, and grassroots advocacy groups striving to make state and local economic development subsidies more accountable and effective. Previously, she worked as an aide for Wisconsin State Rep. Jennifer Shilling (D). Walter earned a master’s degree in urban planning and policy from the University of Illinois at Chicago and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Endnotes