Ensuring that all workers are paid fairly remains an unfulfilled policy goal. Women tend to be paid less than men and racial and ethnic minorities tend to be paid less than white workers. In spite of a number of important reforms over the years to address this problem in the United States, significant pay gaps remain. And in fact, black workers are facing a rising pay gap compared with their white counterparts.1

Research shows that unions and collective bargaining reduce pay discrepancies between women and men and between communities of color and white workers. Moreover, collective bargaining that occurs above the individual firm level, such as at the industry, regional, or national level, is particularly effective at reducing pay gaps compared with the workplace-level bargaining the current U.S. system encourages. The Center for American Progress has proposed moving toward this broader type of collective bargaining in the private sector.2

These findings emphasize the role that labor unions can play in creating a more just society. Unions help change the balance of power in the workplace, while collective bargaining—especially when done above the firm level—provides an opportunity to address explicit and implicit forms of discrimination that can lead to lower pay for women and communities of color. Declining union membership has contributed to increased income inequality and today’s gender and racial pay gaps in the United States.

Reforms to enable all workers to join unions and bargain collectively as well as to promote industrywide bargaining in the private sector would not only raise wages, reduce inequality, and boost productivity—as previous CAP reports have argued3—but would also significantly reduce gender and racial pay gaps.

Specifically, this issue brief finds that:

- Collective bargaining in the United States leads to more equal pay between men and women and between white workers and workers of color.

- Countries with greater collective bargaining coverage and collective bargaining that occurs primarily above the firm level tend to have smaller pay gaps than do other countries. In fact, one academic study found that a country moving from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile of union coverage was associated with a 10 percentage-point decrease in that country’s gender pay gap. Union coverage was even more influential than countries’ minimum wage laws.4

- Research from Australia indicates that its system, where pay is often set by national wage awards, serves to reduce pay gaps.5 CAP has proposed moving toward this kind of system on a path to full industrywide bargaining.6

- Forms of wage-setting in the United States that occur above the workplace level and are therefore somewhat analogous to private sector, industrywide bargaining—such as prevailing wage laws; public sector pay scales and bargaining; and minimum wage laws—lead to smaller gender and racial pay gaps. For example, one analysis found that the income gap between white and black construction workers would be roughly 7 percentage points smaller if a state without a prevailing wage law instituted such a law.7

Benefits of collective bargaining

Collective bargaining reduces gender and racial pay gaps for several reasons. First, it directly raises wages for workers who are covered by union contracts—especially for lower- and middle-income workers. Because women and communities of color are disproportionately represented in lower-wage groups, collectively bargained higher wages for low- and middle-income workers decrease pay gaps. Second, collective bargaining changes how workplaces are run. It helps to sets pay based on objective standards, such as skills and education; creates rules for management to follow, which can prevent harmful policies such as pay secrecy requirements;8 and establishes enforcement mechanisms for workers to ensure these standards and rules are followed. These effects leave less room for pay discrimination and help to secure equal pay for equal work. Third, collective bargaining can and should be designed to secure work-life supports such as paid leave policies, the lack of which can contribute to the gender pay gap.9

Furthermore, unions and collective bargaining help to reduce overall economic inequality broadly in society as more workers receive higher wages under union contracts and nonunion firms compete for workers with union firms. This broader reduction in inequality results in smaller pay gaps as well: The smaller the overall pay distribution in society, the smaller the pay differences tend to be between men and women and between whites and other races and ethnicities.10 In addition, unionized workers have a collective voice to push for policies that further reduce gender and racial wage gaps. Unionized workers are more likely to vote and have an organizational voice in the legislative process pushing for pro-worker policies such as civil rights and equal pay legislation; pay transparency; and paid leave.11

All of these forces are amplified when collective bargaining occurs above the firm level. Bargaining at the industry or regional level generally leads to a greater share of workers being covered by a collective bargaining agreement,12 which means that more workers get pay raises and have their pay based on measurable standards, and there is greater opportunity to address leave policy and other drivers of pay gaps. Moreover, above firm-level bargaining is more effective at reducing economic inequality in society broadly, which leads to greater reductions in gender and racial pay gaps.13

Reducing gender and racial pay gaps will require a number of cultural and political reforms. Among the most important reforms are those that strengthen unions and collective bargaining and encourage collective bargaining to occur at the industry, regional, or national level.

In past reports, the Center for American Progress and the Center for American Progress Action Fund have outlined how the federal government as well as state and local governments can help move in this direction including through the Workplace Action for a Growing Economy (WAGE) Act, the Workplace Democracy Act, and the labor policies in the Better Deal agenda, as well as through a range of additional reforms.14 Necessary reforms include increasing penalties on law-breaking employers and ensuring workers can win recognition for their union and successfully negotiate a first contract; providing bargaining rights to all workers and expanding the right to strike; encouraging private sector, industrywide bargaining through direct measures such as bargaining unit reforms and indirect measures such as wage boards, which bring representatives of workers, employers, and the public together to negotiate minimum standards for pay and benefits for certain industries or occupations; and promoting new forms of worker organization and strengthening funding streams for unions and other worker organizations.

Modernizing U.S. labor laws to strengthen unions, increase collective bargaining coverage, and encourage industrywide collective bargaining would raise wages for workers, increase productivity, and be a positive step toward ensuring equal pay for equal work.

Collective bargaining in the United States reduces gender and racial pay gaps

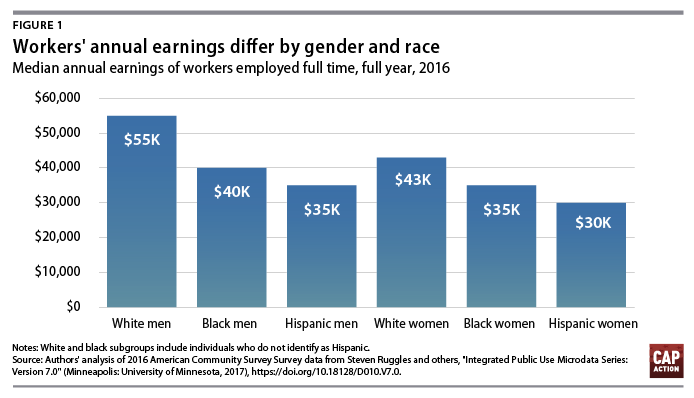

In the United States, the typical female worker earns less than the typical male worker, and the typical worker of color earns less than the typical white worker. These differences—known as pay gaps—are shown in Figure 1 as the difference in median annual earnings between men and women of different races and ethnicities working full-time jobs for the entire year. The gaps can be attributed to many individual and societal factors. Importantly, equal pay is not always provided for equal work—a specific form of inequity. This is typically considered a form of direct, illegal discrimination under federal employment law, which prohibits discrimination based on factors including “race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”15 But gender and racial pay gaps are a result of more than this factor alone. Broader societal discrimination can keep some female workers and workers of color from working at the same types of jobs as white men. Lack of policies that support working families can make it more difficult for women and workers of color to enter higher-paying occupations, as can lack of educational opportunities and the openness of certain career paths. Society and the labor market often help perpetuate these gaps.

Figure 1 shows the differences in median annual earnings received by full-time workers who work the entire year across race and gender from the 2016 American Community Survey. The typical full-time, full-year white male worker reported earning $55,000. In contrast, typical full-time, full-year white female workers earned $43,000, black women earned $35,000, and Hispanic women earned $30,000. Black men earned $40,000 per year and Hispanic men earned $35,000.

The drivers of these differences can be examined through regression analysis, which examines the individual characteristics of workers and their jobs to explain how these factors contribute to the overall pay gap. Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, economists at Cornell University, have examined the gender hourly wage gap in the United States among full-time workers ages 25-64 who worked more than half the year, controlling for differences in industry, occupation, region, race, education, union status, and experience.16

Blau and Khan find that in 2010, different industries and occupations in which women work explain about half the hourly pay gap, with differences in experience levels explaining another 14 percent. Female workers actually had higher levels of education and were more likely to be covered by a union contract, which reduced the pay gap. After controlling for each of these components, Blau and Khan still found that 38 percent of the gap was unexplainable—a measure that is often used to estimate the effect of discrimination. Of course, even the characteristics used as controls can hide effects of discriminatory policies and societal inequities. For example, occupations and industries predominantly held by women can be systemically undervalued, and work experience is affected by the lack of work-life supports in the United States.

Analysis of the racial pay gap from Mary C. Daly, Bart Hobjin, and Joseph H. Pedtke from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco similarly shows that much of this gap cannot be attributed to differences in individual characteristics.17 They examine the composition of the hourly pay gap between black and white workers, which has grown from 1979 to 2016 for both male and female workers. In 2016, black men earned 30 percent less than white men, on average, and black women earned 18 percent less than white women. In 1979, black men earned 20 percent less than white men, while black women earned 5 percent less than white women. Nearly half of this gap for men and more than one-third of this gap for women remains even after controlling for factors such as industry and occupation, education, age, and part-time status. This unexplained gap has actually grown over time: It was just 8 percentage points of the earnings gap for men in 1979, but now stands at nearly 13 percentage points. Similarly, the majority of the rise in the black-white pay gap for women since 1979 was driven by a growing unexplained gap.18 The authors of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco analysis suggest that this gap could include unmeasured factors such as discrimination or differing quality of schools.

Research makes clear that in the United States, union members experience smaller gender and racial pay gaps than their nonunion counterparts. Female union members earn more than their nonunion counterparts, and the overall gender pay gap is smaller for unionized women than for women who are not in a union.19 For instance, analysis from Elise Gould and Celine McNicholas of the Economic Policy Institute using the 2016 Current Population Survey shows that the gender hourly pay gap among full-time workers—controlling for variables including education, experience, and geographic division—drops from 22 percent between nonunion men and women to 18 percent between unionized men and women.20 Research from Marta M. Elvira and Ishak Saporta, from the University of California, Irvine, and Tel Aviv University, respectively, finds that unions have a similar effect on the pay gap within establishments. They examine several industries within the U.S. manufacturing sector and find evidence in a majority of the examined industries that women in unionized establishments experience smaller pay gaps than their counterparts in establishments without unions.21

Research from Jake Rosenfeld and Meredith Kleykamp, academics from Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Maryland, examines the changing wage gap between black and white workers over time and find that the decline of union membership rates has contributed to racial wage inequality. Black workers, especially black women, are more likely to be union members than white workers. This works to close the pay gap between black and white workers. But when union membership declines overall, this effect becomes weaker. Rosenfeld and Kleykamp estimate that had union membership remained at its 1973 levels, weekly wage gaps between black and white women workers would be between 13 percent and 30 percent lower.22

Estimates from the Economic Policy Institute using 2016 data find that unionized black and Hispanic workers receive a 14.7 percent and 21.8 percent hourly wage premium, respectively, over comparable nonunion counterparts.23 In contrast, non-Hispanic white workers receive a 9.6 percent wage premium.24 This larger boost from unionization means that collective bargaining helps to reduce today’s racial wage gap. What’s more, research from Cherrie Bucknor at the Center for Economic and Policy Research finds that wage premiums for unionized black workers without college degrees are even higher.25

Unions also indirectly help reduce pay gaps—even for nonunion members—because increased unionization reduces overall income inequality. Research from Bruce Western and Rosenfeld, of Harvard University and University of Washington, respectively, found that from 1973 to 2007, the decline of unions explained up to one-third of the rise in wage inequality in the United States among men and one-fifth of the rise among women.26 International research confirms that when union density is higher, income tends to be less concentrated among the richest households. According to a study from economists at the International Monetary Fund, a 10 percentage-point decrease in a country’s union membership rate is associated with a 5 percent increase in the income accruing to the richest 10 percent.27

This reduction in overall wage inequality from unionization helps all workers—not just those who are represented by unions. When overall wage inequality is lower, research shows that gender and racial pay gaps are smaller. For example, research from Valerie Wilson and William M. Rodgers III at the Economic Policy Institute finds that the widening of the black-white wage gap in the United States is in part due to growing overall inequality.28 A more compressed economywide pay structure, especially when the lowest-paid workers are closer in pay to those at the median, will reduce gaps among different industries and firms that can lead to gender and racial wage gaps in the economy overall.29 And it also means that even if employers unfairly view the qualifications of women or workers of color as lower than comparable men or white workers, the resulting gaps in pay are smaller. The impact of unionization is reflected in a study of local labor markets by Leslie McCall of Rutgers University, who found that overall black-white wage gaps are lower in metropolitan areas with higher union membership.30

International data show lower pay gaps with more union coverage and higher levels of collective bargaining

The experiences of other countries provide further evidence that union coverage and the type of bargaining have a major impact on the gender and racial pay gaps found around the world. The wide variety of institutional arrangements across countries allows researchers to compare how variances in the share of workers covered by union collective bargaining agreements and the typical level of bargaining affect wage gaps. Studies generally demonstrate that increased union coverage decreases racial and gender pay gaps.31 Furthermore, studies also show bargaining at higher levels, such as by industry, can serve to reduce pay gaps more than firm-level bargaining can, likely because it leads to higher collective bargaining coverage and because it has greater leveling effect on wage differentials between firms and industries.32

Blau and Kahn studied data from 22 countries from 1985 to 1994 and found that countries with more compressed male wage distributions—which were determined in part by greater union coverage and statutory minimum wages—had a smaller wage penalty for women relative to men.33 Blau and Kahn found that, as a result, increased collective bargaining coverage has a significant negative effect on gender wage gaps—and that this effect is stronger than the benefit from minimum wage laws. Their estimates show that a country moving from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile of union coverage within their sample was associated with a 10 percentage-point smaller gender pay gap. After including other country-level controls, the impact of such a move ranges from approximately 8 percentage points to 18 percentage points. More recent research from Khan using 2012 gender pay gap data from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries shows that this relationship still exists: Countries with higher levels of workers covered by union contracts exhibited smaller pay gaps for full-time women, on average.34

Research from the United Kingdom confirms that, like in the United States, unionization serves to reduce gender and racial pay gaps.35 David Metcalf, Kristine Hansen, and Andy Charlwood, from the London School of Economics found that without collective bargaining, the U.K. gender wage gap and the black-white wage gap would be 3.1 percentage points and 3.3 percentage points wider, respectively.

A significant portion of the gender and racial pay gaps in the United States are a result of inequality in pay among industries. Research from Brenda Gannon, Robert Plasman, Francois Rycx, and Ilan Tojerow, of the National University of Ireland Galway and the Université libre de Bruxelles, shows that more centralized forms of collective bargaining can serve to reduce these interindustry differentials.36 Their examination of six European countries found that higher levels of collective bargaining were correlated with smaller differences in wages between industries in a country.

The impact of collective bargaining on gender pay gaps can vary between low-paid and highly paid workers. Using data from Spain, where workers can be covered by national, regional, or firm-based collective bargaining agreements, Florentino Felgueroso, Maria Jose Perez-Villadoniga, and Juan Prieto examined how the level of bargaining affects gender wage gaps at different relative pay levels.37 Overall, the authors report a 5 percentage-point smaller gender pay gap when workers were covered by a higher-level contract compared with a firm-level contract. This is primarily driven by the impact of above firm-level bargaining on lower-wage workers. Among workers who were paid below the median, wage gaps were higher among the workers who bargained at the firm level. However, firm based bargaining—which tends to allow less employer discretion for setting wages of higher-paid workers—was more effective at closing pay gaps among higher-paid workers.

To be sure, increased union coverage and bargaining at levels above the firm level are not a panacea for closing gender wage gaps. The case of Austria provides a cautionary tale: Despite collective bargaining agreements covering more than 9 in 10 workers, the country had the second-highest gender pay gap in the European Union in 2013.38 In Austria, where bargaining largely takes place at the industry level, female-dominated industries tend to have lower minimum pay rates in their bargaining agreements, contributing to increased gender inequality.39 This shows that bargaining partners must consider gender and racial equity at the bargaining table and take care not to extend pre-existing societal inequities by setting compensation standards that disadvantage industries and occupations where women and racial minorities are overrepresented.

Case study: The impact of centralized forms of wage-setting on gender pay gaps in Australia

For more than a century, many Australian workers have had their wages set through a centralized process that combines elements of industrywide bargaining and minimum wage-setting40—somewhat analogous to CAP’s wage board proposal.41 State and federal arbitration tribunals would hear testimony from worker and employer representatives and then set minimum wage rates for certain industries or occupations. In 1907, a federal court case determined a basic “fair and reasonable” minimum wage rate; over subsequent decades, tribunals began to take this wage rate into account when setting wage awards, providing additional wage supplements to more skilled employees.42

This centralized form of wage-setting initially made it possible to explicitly institute discriminatory pay practices: In early years, employers had to pay women in traditionally female industries only 54 percent of the male pay rate.43 But more centralized pay structures also made it easier to reduce pay discrimination: After 1972, award wages were equalized for men and women and instituted the principle of equal pay for work of equal value.44 And some Australian states established even stronger principles on equal pay that workers could use to challenge discriminatory pay arrangements. For example, a commission in New South Wales found in 2002 that librarians—a predominantly female occupation—were not paid fairly compared with male-dominated public sector jobs and subsequently raised their pay by an average of 16 percent.45

A study from Michael P. Kidd and Michael Shannon looks at the overall impact of Australia’s industrial relations structure on pay inequities. They examine why the hourly gender pay gap in Australia in 1989, where women were on average paid 15 percent less than men, was less than half as large as Canada’s in the same year. In Australia at the time, nearly 4 in 5 employees’ wages were set through the country’s industrial tribunal system. Canadian wage bargaining, in contrast, was much more decentralized. Roughly one-third of Canadian workers were covered by a firm-level union contract and two-thirds bargained individually without union representation.46 Kidd and Shannon found that the difference in labor market institutions explained more than half of the difference in the gender wage gap between the two countries.

Since that study was conducted, Australia has gone through several rounds of reforms to its wage-setting institutions. Reforms passed in 1993 and 1996 encouraged firm- and individual-level bargaining, with limited wage awards serving as a safety net. Radical changes that dramatically curtailed the power of labor tribunals were implemented for a brief period of time after 2005 but were replaced in 2009 by the Fair Work Act, which currently governs Australian labor relations.47 Under this law, the awards system was simplified, and Australian workers are now covered by 122 so-called modern awards that set minimum wages for different classifications of workers in a given industry or occupation.

These modern awards dictate the pay of fewer Australian workers than tribunals of the past. But they still have an impact on reducing gender pay gaps. A working paper from Barbara Broadway and Roger Wilkins finds that the gender gap in hourly pay among workers whose pay is set by awards is nearly half the size, or 10 percent, of the 19 percent gap among workers whose pay is set by other methods.48 However, they do find evidence that award payments—for both men and women—are lower in industries and occupations typically held by women.49 Similarly, 2015 data from Australia’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency shows that the gender pay gap in weekly earnings is smallest—9.2 percent—among workers whose wages are set by award, followed by workers whose wages are set by largely firm-level50 collective agreement—16.5 percent—and those whose wages are set through individual arrangements—21.7 percent.51

The Australian experience shows that more centralized types of pay bargaining can effectively reduce gender pay gaps, so long as the principle of equal pay for equal work is considered when pay levels are being determined.

More centralized forms of wage-setting close pay gaps in the United States

The research described earlier in this brief makes clear that the U.S system of primarily firm-based collective bargaining significantly reduces gender and racial pay gaps, but countries with greater collective bargaining coverage and especially systems with bargaining above the firm level tend to have smaller pay gaps. The U.S. experience in the public sector, prevailing wage, and minimum wage laws provide additional evidence to suggest that moving toward industrywide bargaining would lead to even lower gender and racial pay gaps. Pay scales that are often found in the public sector, prevailing wage laws that ensure wage standards across occupations, and minimum wage laws that bring up the wages of low-paid workers are somewhat like industrywide bargaining in that they set wages or wage floors across multiple worksites. This helps to reduce gender and racial pay gaps.

The public sector is a major employer of women and workers of color, due in part to past and present commitments to providing equal opportunities for all workers. As a result, women and African Americans hold a disproportionately high share of government jobs.52 But hiring practices are not the only factor distinguishing the public sector from private employers. Wage-setting in the public sector is typically more centralized than the individualized method largely found in the private sector. For example, take the predominant wage-setting structure for U.S. federal government workers: the General Schedule (GS) pay system. In 2017, the GS system covered nearly 1.5 million workers, or about 7 in 10 federal workers.53 Federal agencies classify positions into one of 15 pay grades using a set of uniform standards within set occupational categories.54 There are 10 steps within each pay grade, and workers can move up one or more steps based on their years of work and performance.

By focusing more specifically on measurable employee characteristics, such as education, and specific job responsibilities found in a given occupation, these more centralized pay structures reduce the amount of gender and racial pay discrimination. For example, in 2012, female workers paid through the GS system were paid 10.8 percent less annually than male workers,55 which is dramatically lower than the overall pay gap of 23.5 percent among all—including the private sector—full-time, full-year workers that year.56 Regression analysis from the U.S. Office of Personnel Management finds that 3.8 percentage points of this gap are unexplained by measurable factors.57

This unexplained gap could be due to discrimination or other unmeasured factors such as prior work experience outside of the federal government.

Studies that examine the U.S. public sector broadly—including federal, state, and local government workers—also show that women and workers of color face lower pay gaps than private sector workers. Hadas Mandel and Moshe Semyonov, sociologists at Tel Aviv University, examined U.S. weekly earnings data and found that in 2010, the public sector gender pay gap was one-fifth less than the private sector gender pay gap.58 Occupational differences explained twice as much of the gender pay gap in the public sector compared with the private sector gap. This is to be expected from a centralized structure where pay is more similar within occupations. The fact that occupational differences explain a larger share of the public sector gender pay gap serves as a reminder that some occupations predominantly filled by women can be systemically undervalued compared with predominantly male occupations.59 Care must be taken to ensure that collective bargaining at the industry or occupation level serves to close these divides.

University of Wisconsin sociologists Eric Grodsky and Devah Pager similarly find that the racial pay gap is smaller between white and black male workers in the public sector than in the private sector.60 Black male workers earned 34 percent less per hour than their white male counterparts in the private sector, compared with 24 percent less in the public sector. Furthermore, analysis from John S. Heywood and Daniel Parent, economists at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and HEC Montréal, respectively, finds that the black-white wage gap in the private sector grows dramatically at higher income levels but remains generally flat across the income distribution in the public sector. This shows that pay scales can help reduce pay gaps for both low- and high-income workers.61

Analysis from David Cooper, Mary Gable, and Algernon Austin at the Economic Policy Institute finds that African American and Hispanic workers employed by U.S. state and local governments experience smaller racial pay gaps than do white workers, compared with their counterparts in the private sector.62 After controlling for factors including education, experience, region, and organization size, African American and Hispanic workers in the state and local public sector were paid 2.2 percent and 2.9 percent less, respectively, than comparable white workers.63 These gaps were dramatically higher—12.9 percent for African American workers and 11.1 percent for Hispanic workers—in the private sector.64

Evidence from another type of pay-setting structure in the United States, prevailing wage laws, suggests that industry- or regionwide bargaining would reduce pay gaps. The federal government and many state governments require that workers on public construction jobs be paid at least a government-determined prevailing wage. This wage, which differs based on occupation and is based on local market wage rates, ensures that government spending will not drive down labor standards.

Researchers Jill Manzo, Robert Bruno, and Frank Manzo IV of the Illinois Economic Policy Institute examine how the prevailing wage affects racial equity using the fact that some states do not require prevailing wages to be paid on state construction work.65 After controlling for several demographic and economic factors, they find that white construction workers in states with prevailing wage laws see 17 percent higher incomes than in states without such laws, but black construction workers see a larger 23.6 percent benefit on average. As a result, the authors estimate that if a state without prevailing wage laws was to implement such a law, it would close the white-black pay gap among construction workers by about 7 percentage points.

Another type of wage-setting that occurs above the firm level—changes to the U.S. minimum wage—also has had an effect on the gender and racial wage gap. When examining the change in the gender wage gap from 1979 to 1988, Blau and Kahn estimated that had the minimum wage not declined in real terms, the overall gender pay gap would have been 1.6 percentage points smaller.66 As to be expected, the minimum wage had the largest impact on workers who are most likely to be paid this wage—those with less education or experience. The gender gap would have been narrowed by an estimated 5 percentage points among the lowest-skilled workers had the minimum wage retained its value. Researchers have found that states with a lower minimum wage tend to have higher gender wage gaps. According to the National Women’s Law Center, in 2015, women in states with minimum wages of at least $8.25 per hour had a pay gap of 13.5 percent, compared with the 23 percent gap in states with the federal minimum wage of $7.25.67

Conclusion

It is crucial that policymakers act to boost the pay of American workers and ensure that prosperity is broadly shared. Today’s high levels of income inequality, which are in part driven by the decline of union membership, contribute to the existing gender pay gap and growing racial pay gap. While many policies would help address these problems, the research presented in this brief demonstrates that reforms to allow more workers to bargain collectively—especially across multiple employers—would play a major role in reducing these gaps.

Achieving this reform will not be easy: American labor law has seen no major changes since the Taft-Hartley Act, which weakened union power, became law in 1947.68 But putting forth the effort would be worth it. Updating the nation’s labor law system so that more workers can bargain collectively and so that more bargaining occurs at the industry or occupation level—such as through the creation of wage boards—would raise wages and reduce inequities across gender and racial lines.69 Pro-worker state and local lawmakers should take action to move toward such a system in their own jurisdictions.70 And lawmakers at the national level aiming to solve the nation’s ongoing problems of stagnant wages, growing inequality, and unequal pay of women and workers of color should commit to rebuilding worker power through a modernized form of collective bargaining.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Alex Rowell is a policy analyst for Economic Policy at the Center.

Endnotes