On July 16, a New York Times story raised concerns about a proposal from the Hillary Clinton campaign to increase federal support for public colleges. The piece argued that the proposal could lead directly to tuition price increases. Giving credence to a theory that is rooted in punditry instead of proof is unfortunate because the types of incentives and structures put forward by the Clinton campaign are the nation’s best shot at concrete steps to keep prices in check.

Sadly, the alleged link between federal aid and tuition prices has been hanging around for nearly 30 years. It started in 1987, when then-Education Secretary William Bennett took to the Times op-ed page to defend proposed cuts to federal financial aid. To deflect attention away from the Reagan administration’s spending reductions, Secretary Bennett derided the performance of America’s colleges and universities. His attack was elegant in its simplicity: Rather than helping keep college affordable, he argued that increases in federal financial aid would help schools raise their prices. Known now as the “Bennett Hypothesis,” this claim is a persistent conservative talking point.

While the hypothesis may make for nice quotes, the evidence supporting it is at best inconsistent and thin. In fact, there is no convincing evidence to support Secretary Bennett’s claim in the case of public colleges, where former Secretary of State Clinton proposes to spend additional federal funds. The hypothesis also makes little sense when considering the history of increases in the federal aid programs, declines in state funding, and the change in institutional revenue.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that the Bennett Hypothesis is a far better sound bite than serious economic theory. Here are four reasons to be skeptical of the claim that federal financial aid will drive up public college prices.

Researchers cannot confirm links between federal aid and public college prices

The research base behind the Bennett Hypothesis is not sufficiently consistent and rigorous to justify its persistence. Federal reviews of the literature have failed to turn up conclusive and consistent evidence of the theory’s effects, especially at public colleges.

Most recently, a 2014 literature review by the Congressional Research Service, or CRS, found weak and inconsistent conclusions about the connection between federal aid and college prices, especially at public colleges. It identified nine studies published since 2000 that had what it deemed to be sufficiently rigorous methodology. The CRS found no consensus across the reports about the effects of student aid on price. It also found that studies produced wildly different results simply by making changes to their underlying model and assumptions. Furthermore, of the seven studies with findings applicable to public colleges, four found evidence that is generally not supportive of the Bennett Hypothesis. Only one found evidence generally supporting it. That 2004 study looked only at the most elite public four-year colleges. In addition, the CRS raised questions about the authors’ different models with different findings.

Tuition goes up even when federal aid does not

A basic review of financial aid policy presents the first major challenge to the Bennett Hypothesis: Federal aid increases are generally erratic and inconsistent, while tuition goes up each and every year.

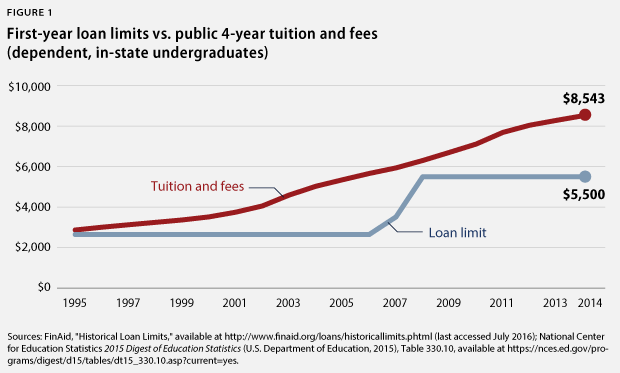

Federal student loan limits in particular illustrate the weakness of blaming tuition increases on financial aid. The figure below shows the maximum amount that dependent undergraduate students could borrow in their first year vs. the average tuition and fees for students to attend a public, four-year institution in their home state from 1995 to 2014. The maximum loan limits changed only twice in this period. Tuition rose every year. In fact, college prices rose by more than $4,130 even as the loan limit remained unchanged from 1987 through 2006. Similarly, according to Center for American Progress analysis, the loan limit has not changed since 2008, even as tuition and fees went up by more than $2,200.

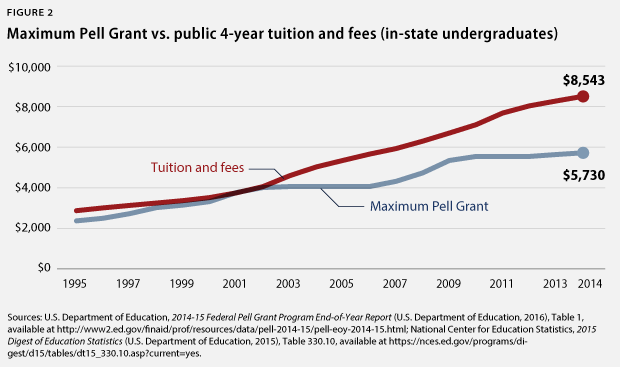

The Pell Grant shows a similar pattern. Congress did not create regular, planned increases to the maximum award until 2007. Prior to that, the Pell Grant increased only when Congress chose to raise it. As a result, the maximum grant stayed stuck at $4,050 from 2003 to 2006. Tuition and fees at public four-year colleges went up by more than $1,000 during that time.

Tuition increases are tightly connected to state funding declines

Although federal student aid may not have changed in most years, something else did: state funding. The evidence is overwhelmingly clear—reductions in state funding are the single-largest driver of public college tuition increases. When a state withdraws funding from public colleges, it creates a hole in their budgets. To fill that gap, schools raise prices so students provide more revenue from tuition.

In fact, public college price increases are very similar to state funding cuts on a per-student basis. According to a CAP analysis of data from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, the amount colleges collected from tuition over the past 10 years increased by $1,683 per student, while state funding declined by $1,382 per student.

Public colleges are not pulling in more revenue

If institutions were using federal financial aid to greedily raise prices, then charging students more should increase overall revenue received. Yet revenues per student are largely unchanged. According to data from the Delta Cost Project, revenues per student at public four-year colleges were nearly identical in 2008 to what they were in 2013. At the most elite colleges, revenues were 2 percent higher, while less selective colleges saw declines of 3 percent to 6 percent.

In other words, public colleges are not using federal aid increases to take in more money. Federal aid is making up for massive budget holes that would otherwise have been left by declines in state investment. This is a finding confirmed by New America’s April 2016 analysis of college funding, which found that increased federal aid essentially replaced lost state funding for low-income students.

Conclusion

While the Bennett Hypothesis has weak underpinnings, it correctly voices one frustration: College prices continue to rise. These tuition hikes can make college feel out of reach, even for students who benefit from generous federal financial aid. And for those in the middle class who may not qualify for substantial aid, rising prices may make college increasingly difficult to afford.

Cutting or freezing federal aid, however, will not solve the price problem. Ironically, the type of proposal put forward by the Clinton campaign that generated the New York Times criticism is probably the best hope for arresting tuition growth. It ensures that students get a specific outcome—free college for those below a certain income level—and provides a set amount of additional funds to get there. This requirement ensures that the combination of new and existing federal aid, plus money from the institution and state, is enough to provide tuition-free college to students. Such guarantees are missing from the current system.

That may not make for a fun pop theory, but unlike the Bennett Hypothesis, it’s actually grounded in reality.

Ben Miller is the Senior Director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress Action Fund.