In the election season of 2016, then-candidate Donald Trump visited Wisconsin nine times to speak with potential voters at town hall events and rallies.1 At an event in Eau Claire just a few days before the general election, Trump told a crowd, “America has lost one-third of its manufacturing jobs since Bill and Hillary’s NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement]”—and promised, “That’s going to be changed around.”2

Yet nearly three years after Trump’s inauguration, the data increasingly show that the administration has not helped working-class Wisconsinites; in fact, its policies have only exacerbated economic issues in Wisconsin—especially in areas that supported Trump in the 2016 election.

2018 started with a trade war prompted by the Trump administration levying tariffs on countries across the globe, from European, Asian, and North American allies, to China, an economic rival. Estimating the costs of tariffs to consumers is difficult, but based on the most recent policy announcements from the White House, one study suggests that the average family paid an additional $1,315 in 2019 alone.3 Many working-class Americans will surely notice tighter budgets if they haven’t already. Even so, only certain areas will feel the majority of the economic pain, which stems from job losses and factory closures. States in the Upper Midwest, such as Wisconsin, are bearing the brunt of his chaotic policies.

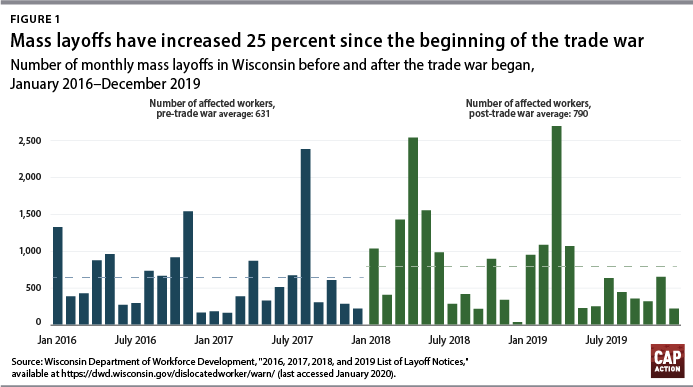

First, consider mass layoffs: Under Wisconsin state law, employers who plan to lay off employees en masse must submit advance written notice to the Department of Workforce Development. In the two years leading up to the start of the trade war, 15,154 workers were affected by mass layoffs in Wisconsin. In the two years following, that number jumped to 18,949 workers—a 25 percent increase.4

The Trump administration claims that its trade policies will help the country, but many experts disagree. Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, noted recently, “To argue that this [the trade war] isn’t doing economic damage is just wrong.” These effects are evident in Wisconsin.5

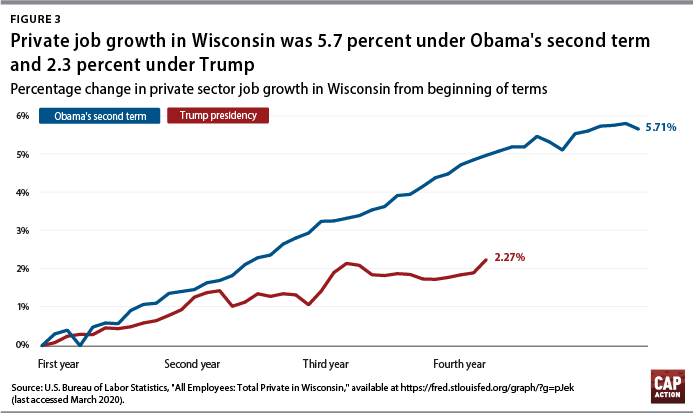

In terms of private employment:

- Wisconsin added 136,200 jobs under President Barack Obama’s second term. Under Trump’s presidency so far, that figure is only 57,500.6

- In the two years since the Trump administration’s trade war began, Wisconsin added 25,200 jobs—less than half as many as in the two preceding years.7

- Under Obama’s second term, Wisconsin experienced a 5.71 percent increase in job growth. So far under Trump’s presidency, that figure stands at just 2.27 percent, with significant deceleration starting soon after the trade war began.8

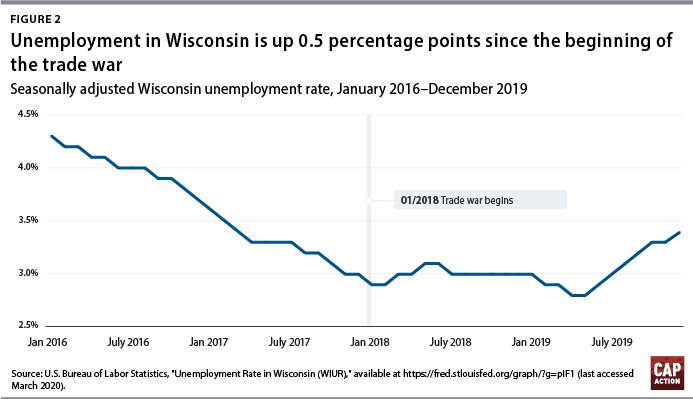

Moreover, Wisconsin’s overall seasonally adjusted unemployment rate had been steadily decreasing for the four years prior to Trump’s election and continued to do so until almost immediately after the trade war began. Now, the rate sits at a nearly three-year high of 3.4 percent—0.6 percentage points higher than it was in the middle of 2019.9 As the Trump administration continues to pursue open-ended trade policies, Wisconsin workers are hurting.

While average families are noticing higher prices for essential goods, the wealthy have received outsize benefits from the Trump administration’s tax cuts passed in the so-called Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). A report by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy estimates that in 2020, the richest 1 percent in Wisconsin will receive an average tax break of $39,610—more than 98 times larger than the average tax break of $403 given to the bottom 60 percent of Wisconsinites.10

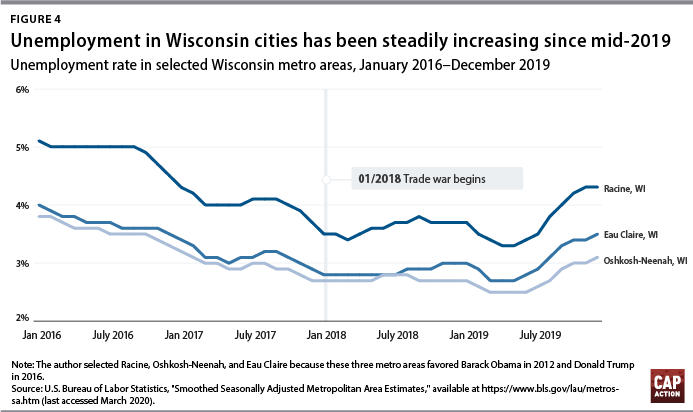

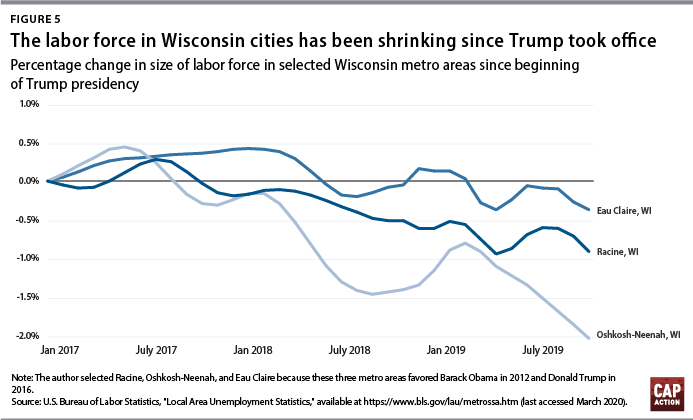

Disparities exist even within the state, as the effects of the trade war, tax cuts, and this administration’s overall economic policies have hit some parts of Wisconsin particularly hard. The three Wisconsin metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) that favored Obama in the 2012 election and Trump in 2016 have been faring particularly poorly since Trump entered the White House: Eau Claire, Racine, and Oshkosh-Neenah.

Eau Claire

The Eau Claire MSA, which includes Chippewa and Eau Claire counties, favored Barack Obama in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections but voted for Donald Trump in 2016. During Obama’s final years in office, the unemployment rate was steadily decreasing, and the Trump administration inherited much of that economic momentum. Yet the Trump administration’s economic policies are starting to reverse this trend.

The monthly change in the Eau Claire metropolitan area’s unemployment rate stopped decreasing in March 2019, became positive in June 2019, and has been increasing ever since. In December 2019, the last month for which data are available, the unemployment rate stood at 3.5 percent—up 0.8 percentage points from the yearly low of 2.7 percent and the highest it’s been since 2016.11

In addition to the rise in the unemployment rate, the labor force has actually started to shrink. Prior to the Trump administration’s trade war, the size of the labor force stayed the same or increased in each month of his presidency. In 16 of the 24 months following the initiation of the trade war, there was monthly decline, and the labor force in December 2019 was down more than 700 people since its peak in February of 2018.12

The Trump administration also incentivized offshoring through the TCJA.13 Ten mass layoffs have occurred in the Eau Claire area since the Trump administration initiated the trade war, affecting at least 410 workers.14 Radial, an operational services multinational corporation headquartered in Pennsylvania, operated a call center in Eau Claire with 142 employees. On March 26, 2019, Radial submitted a notice required by the federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) Act to alert the state that the Eau Claire center would close permanently.15

Several other firms, including Syverson, Bon-Ton Stores, Schuman, Shopko, Iron Mountain Trap Rock Co., Intel Corp., and US Bank, have all joined Radial in issuing WARN Act notifications in Eau Claire since the trade war began.16

Racine

Racine, another metro area that favored Barack Obama in 2012 and Donald Trump in 2016, has likewise experienced economic distress since the start of the Trump administration’s trade war. The Racine MSA saw its unemployment rate drop from 7.4 percent at the beginning of Obama’s second term to 3.4 percent at the end of it.17

Yet the Trump administration’s trade policies and corporate tax cuts have reversed this trend in the Racine MSA. After a decline in the unemployment rate that had lasted for years—a trend that long preceded the 2016 election— Racine has more recently seen a significant upswing in the unemployment rate since the second quarter of 2019. In December 2019, the unemployment rate sat at 4.3 percent—1 full percentage point higher than the low of 3.3 percent experienced in April 2019.18

Similar trends are apparent in the Racine metro area’s labor force: Its size peaked in August 2017 at slightly more than 100,000 after roughly 18 months of consistency. Today, it sits below 99,000 and looks likely to continue decreasing.19

Racine has also been negatively affected by the wave of mass layoffs in Wisconsin. Since the trade war started, 10 mass layoffs have occurred in the metro area, affecting at least 452 workers.20 One such mass layoff, initiated by Cordstrap USA, which makes strapping for cargo-securing systems, is emblematic of the decline in manufacturing activity in Wisconsin. Moreover, the layoff highlights the Trump administration’s shortcomings on the promise of restoring the manufacturing sector. Cordstrap opened its Racine metro manufacturing plant in 2000, but now, amid an uncertain trade climate, the multinational corporation has decided to move its production facilities overseas.21

Oshkosh-Neenah

The Oshkosh-Neenah metro area, which comprises Winnebago County, is the third Wisconsin MSA that voted for Obama in 2012 and Trump in 2016. Like the Eau Claire and Racine MSAs, Oshkosh-Neenah has been severely affected by the Trump administration’s trade policies. Six mass layoffs have affected at least 257 workers in the metro area since the beginning of 2017.22

Kimberly-Clark—a fabric manufacturing firm—closed two locations over this time period, leaving 65 workers jobless.23 Silver Star Brands, an electronic shopping and mail-order service, likewise closed shop in Oshkosh, noting that it decided to outsource the 62 jobs that it cut.24

And just like the other Wisconsin Obama-Trump MSAs, Oshkosh-Neenah has recently experienced an increase in its unemployment rate and a decrease in the size of its labor force. December 2019 saw an unemployment rate of 3.1 percent—a 0.6 percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate compared with the low of 2.5 percent reached in June 2019.25 The Oshkosh-Neenah labor force has shrunk by 2,300 from its peak of more than 94,100 workers immediately after Trump assumed office to a slightly less than 92,000 workers in December of 2019.26

Conclusion

Trump entered office with promises to help forgotten communities and workers, including in Wisconsin. Yet the economic data tell a different story—one of increased unemployment, discouraged workers, and mass layoffs. Unfortunately, it is the voters who helped elect Trump who are most negatively affected by his administration’s economic policies.

Ryan Zamarripa is the associate director of Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress Action Fund.

Endnotes