By Tom Jawetz

Last month, Republican leadership in the U.S. House of Representatives took the unprecedented step of filing with the U.S. Supreme Court a purely partisan amicus brief that purported to represent the will of the whole House. This, despite the fact that 186 members of the House already were on record as opposing the position that would be expressed in the brief and 186 Democratic and Republican members voted against the resolution authorizing the House to file the brief. The brief was filed in a case, United States v. Texas, involving a challenge by Republican governors and attorneys general from 26 states to two immigration enforcement policies: Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, or DAPA, and expanded Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or expanded DACA. When the lawyer chosen by Speaker Paul Ryan, Erin Murphy, took to the podium on Monday to present the House’s arguments, she advanced three arguments that were misleading and false, and were designed to drive a political narrative rather than a legal one. Here is why they were wrong.

Falsely Equating Deferred Action and Permanent, Lawful Status

In her opening comments, Murphy presented an argument intended to support the House’s contention that the administration overstepped its authority and took actions that only Congress can take. She told the Court that in 2013, the administration unsuccessfully tried to get Congress to pass immigration reform so that unauthorized immigrants could obtain legal status. Unable to enact legislation, Murphy argued, the administration adopted DAPA and expanded DACA “to achieve the same” end that the legislation had failed to achieve. This built upon a similar argument the House made in its written submission to the Court — namely, that when Congress failed to enact the DREAM Act in 2010, the administration in 2012 announced DACA, which was “designed to achieve the same result as the proposed but un-enacted DREAM Act.”

This argument is not new, but it is uniquely offensive when expressed by the House of Representatives in its official capacity at the Supreme Court. Just as DACA does not now, and was never intended to, achieve the same result as the DREAM Act, DAPA and the expansion of DACA could never achieve the same result as real legislative reform. These legislative reforms would put people on a pathway to permanent legal status and eventual citizenship. By contrast, DACA, expanded DACA, and DAPA provide only temporary relief from the threat of deportation and, by virtue of separate and preexisting legal authority, the ability to apply for work authorization. These policies — and the protections they offer — are discretionary, and could be revoked at any time.

To be sure, DACA has helped to transform the lives of more than 700,000 young people, many of whom have enrolled in higher education, gotten better jobs, increased their wages, and contributed more fully to their families and communities. But protection under DACA expires and must be renewed every two years. DACA does not provide a path to lawful permanent residence or citizenship. DACA does not provide a defense from deportation or any form of lawful immigration status. And while DACA beneficiaries may enjoy a measure of comfort for the time being, it does little to allow them to engage in the kind of long-term planning that would benefit them, their families, and the country as a whole. Here’s how Yehimi Cambron, a DACA beneficiary in Georgia who is now teaching students as a Teach for America corps member, recently explained that point:

“I have two years. I can work, and I can drive, and I don’t have to be scared with a police officer driving next to me,” said Cambron, who added that she’s grateful for DACA, but said it’s hard to plan ahead. “Where do I want to be in 10 years? Where do I want to be in 5 years? I know where I want to be, but I can’t plan for that. We need something more long-term, something more inclusive.”

Blurring the lines between deferred action — a decades-old practice of tolerating a person’s continued presence in the country — and lawful permanent residence and citizenship may advance the House’s political argument, but it is irresponsible and beneath the House as an institution to mislead the Court about what a legislative solution could provide that DAPA, DACA, and expanded DACA never could or would. Perhaps that is why the actual litigants in the case — the states suing to block the deferred action policies from going into effect — do not share the House’s view and conceded in writing and again during the argument that the administration has the authority to set immigration priorities and even to issue to certain unauthorized immigrants “‘low-priority’ identification cards,” or, as it has been called for around 40 years, “deferred action.”

Rewriting History about Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush’s Family Fairness Policy

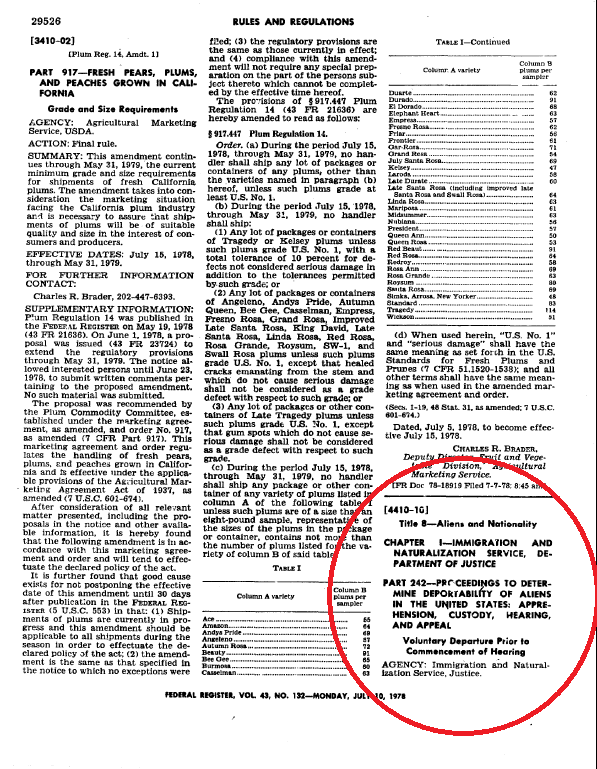

One of the strongest historical precedents for DAPA, DACA, and expanded DACA is the Family Fairness policy adopted in 1987 by President Ronald Reagan and expanded in 1990 by President George H.W. Bush. In 1986, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, or IRCA, which allowed nearly 2.7 million unauthorized immigrants to obtain lawful permanent residence but intentionally provided no relief to their unauthorized spouses and children who were unable to independently qualify for relief. The Family Fairness initiative allowed up to an estimated 1.5 million spouses and children of IRCA beneficiaries to register with the government and request “indefinite voluntary departure,” or permission to remain in the country.

When pressed on this historical precedent by Justice Elena Kagan, Murphy responded that, “There was a statute on the books at the time that permitted extended voluntary departure.” Scott Keller, the Texas Solicitor General, made the identical argument, responding to a question by Justice Sonia Sotomayor by saying that, “the Family Fairness Program, first of all, was done pursuant to statutory authority. It was a voluntary departure program. It was not an extra statutory deferred action program.”

The purpose of their argument was to show that whereas indefinite or extended voluntary departure was granted under the Family Fairness policy pursuant to statute, any deferred action granted under DAPA and expanded DACA would be without such statutory authority. It could be a very powerful argument if there was any merit to it at all, but that just is not the case.

It is true that a statute existed at the time allowing certain people in deportation proceedings to be granted voluntary departure so that they could leave the country without receiving a formal order of deportation. But that statute had precisely nothing to do with the separate practice of allowing people, whether or not they were in deportation proceedings, to affirmatively request permission to remain in the country indefinitely. It is this latter practice that was called extended voluntary departure, or EVD, and — contrary to the similarity in name — it was never understood to be grounded in the voluntary departure statute itself. In fact, the final rule promulgating the regulation relies only upon 8 U.S.C. § 1103(a), a provision that grants the Secretary of Homeland Security exceedingly broad authority to “establish such regulations; … issue such instructions; and perform such other acts as [the Secretary] deems necessary for carrying out his authority” under the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Similarly, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in a 1988 opinion described EVD as falling within the “broad mandate” of section 1103(a) and a separate opinion in the case filed by Judge Laurence Silberman said, contrary to Keller’s argument to the Court, that EVD was, in fact, an “extrastatutory decision to withhold enforcement.” Section 1103(a) remains in force today and, together with a separate provision charging the Secretary with the responsibility of “establishing national immigration enforcement policies and priorities,” provides strong legal authority for the policies at issue in this case. Family Fairness remains the most relevant — but by no means the only — historical precedent for DAPA and expanded DACA.

Ignoring Decades of Historical Practice and Legal Authority for the Granting of Work Authorization

Shortly before her time expired, Murphy was asked by Justice Kagan whether the administration could adopt any policy, however small, to allow unauthorized immigrants to work lawfully. Murphy responded definitively: “Congress has passed a statute that says if you are living in this country without legal authority, you cannot work. That’s Congress’s policy judgment in [8 U.S.C. §] 1324a.”

In fact, section 1324a nowhere says that a person who is living in this country without legal authority cannot, under certain circumstances, be permitted to work lawfully and the text of the provision and its history make it clear that the opposite is true.

Section 1324a prohibits employers from hiring or recruiting a person that they know to be “an unauthorized alien (as defined in subsection (h)(3)) with respect to such employment.” Already there you can see that the touchstone for the analysis is not whether the person seeking employment lacks authorization to live in this country, but rather whether the person is unauthorized “with respect to such employment.” The definition provided in subsection (h)(3) clarifies things even further. It reads: “the term ‘unauthorized alien’ means, with respect to the employment of an alien at a particular time, that the alien is not at that time either (A) an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence, or (B) authorized to be so employed by this chapter or by the [Secretary of Homeland Security].”

Throughout the 1970s, Congress regularly considered — and, in the case of the Farm Labor Contractor Registration Amendments Act, enacted — legislation recognizing the authority of the Attorney General at the time to grant employment authorization. The INS also took steps to codify the practice, promulgating in 1981 a regulation that permitted multiple categories of people who were present without any lawful immigration status to request permission to nevertheless work lawfully. The regulation was challenged in 1986 as being inconsistent with the immigration laws, but Congress enacted section 1324a later that year before the agency had an opportunity to respond. The following year the INS formally rejected the challenge on the grounds that the only way to understand what Congress meant when it included the phrase “or by the Attorney General” in the statute was that Congress was fully aware of the 1981 regulation and intended to preserve the authority of the executive to grant employment authorization by regulation. In fact, the agency went one step further and amended the 1981 regulation to add section 1324a as an additional source of the legal authority for granting work authorization to categories of persons who may not have lawful immigration status. Over the last 35 years, Congress has taken no action to amend the law and that 1981 regulation has not since been challenged — even in this case.

Credit: America’s Voice

Credit: America’s Voice

It is also worth noting that if the House’s argument was correct it would disrupt much more than just the ability to offer work authorization to people who receive deferred action. As Solicitor General Don Verrilli explained in his briefs and again during oral argument, the Department of Homeland Security has long authorized — pursuant to regulation — work authorization for people who have applied to adjust their status to lawful permanent residence or for cancellation of removal, a form of relief available to people in removal proceedings. Neither of these categories of people necessarily has lawful immigration status during the pendency of their applications and there is no distinct statutory authority to grant employment authorization to such persons by virtue of their pending applications, yet both categories have, for decades, routinely received employment authorization by virtue of the regulation in extremely large numbers. As Solicitor General Verrilli attested to during the oral arguments, since 2008, 3.5 million people have received work authorization as part of the application process for adjustment of status, and 325,000 people have received it as part of the same for cancellation of removal.

Conclusion

From the moment then-Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano announced the creation of DACA in 2012, House Republicans have been singularly focused on terminating the policy come hell or high water. On multiple occasions they have brought to the Floor bills that would block DACA and/or prevent the 2014 deferred action policies from taking effect and some have threatened to bring the federal government to the brink of complete or partial shutdown to achieve this end.

The brief that they filed with the Supreme Court, and the arguments they presented in Court, can only be understood through that lens. Despite their best efforts to pass legislation to curb the Secretary’s authority to implement these policies, House Republicans have been unable to work their will through Congress. So, like the Republican state-elected officials who took their policy (and political) grievance to the courts for resolution, House Republicans have now thrown their political fight into the judicial arena where it does not belong. If the Court sees it for what it is and decides the case on the law, it will reject the misleading arguments of the House (and the state plaintiffs) and lift the injunction blocking implementation of DAPA and expanded DACA.

Tom Jawetz is the Vice President for Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress Action Fund