It is highly likely that unions will soon be under attack at the federal level. The exact nature of the attack is still in question, but based on recent state actions—including the passage of new right-to-work laws and attacks on public sector workers’ bargaining rights—and bills that have been introduced in both this and recent sessions of Congress, it is clear the attacks will come.

This issue brief delves into these recent threats to unions, specifically exploring a category of attacks on worker power that would make it harder for workers to organize by undermining the union formation process. Previous and forthcoming reports from CAP Action highlight other likely attacks on unions, such as so-called right-to-work and paycheck protection legislation.1

Workers seek to form a union so that they can have a stronger voice on the job and improve their working conditions, pay, and benefits. Study after study shows that, when workers come together in unions, they help make things better not only for themselves but also most Americans. Thanks to increased bargaining power, union members’ wages are on average about 14 percent higher than comparable nonunion workers, and they are more likely to have retirement benefits, health insurance coverage, and paid leave.2 And nonunion employers are often pressured to respond to keep up with higher pay at unionized workplaces: When unions are strong, higher wages and benefits spill over into other nonunion workplaces.

Unions of working people also help ensure that government works for everyone—not just those at the top—by encouraging people of modest means to vote and by providing a crucial counterbalance to wealthy interest groups.3 In fact, unions are some of the only groups who advocate for middle-class interests.4 Their ability to improve conditions in the workplace and in our democracy means that unions play a critical role in building the middle class. However, their strength in these political efforts unfortunately makes them a target for conservative lawmakers and their wealthy backers attempting to push through a corporate-backed agenda against the economic interest of most American workers.

The process that workers have to go through to form a union is exceedingly and unnecessarily difficult. Indeed, research indicates that more than half of nonunion workers would vote to form a union, yet only 11 percent of workers are union members.5

The so-called reforms union opponents advocate for would only make a flawed system worse and even less democratic. While proponents of these reforms claim that they are looking out for workers, their efforts are best understood as an effort to weaken workers’ ability to join together in unions and serve as a countervailing power against corporate interests. If unions are weakened even further, there will be fewer checks on the power of corporations in the workplace and the economy at large.

Some of the harmful proposals to change the union election process would count nonvoters as opposing the union, creating a new definition of voter majority that few members of Congress achieved in the 2016, or any, election.6 Other proposals would allow employers to delay elections.7 And some proposals would strip workers’ rights to petition for voluntary recognition from their employer and instead require secret ballot elections, ignoring that a free choice—and true democratic action—requires not just a ballot but also that voters are free from intimidation, harassment, or attacks from powerful figures and have access to information from all sides.8

When these attacks come—whether as a stand-alone bill, an amendment, or through regulatory action—policymakers that support workers’ rights to form and join unions need to be ready. Rather than making a flawed system worse, policymakers should seek to ensure that workers have fair and democratic processes to choose whether to form or join a union. At a minimum, that means continuing to allow employers to voluntarily recognize a union if a majority of workers demonstrate their support by signing cards, preserving the existing outlet to the broken system. Yet, to truly address the anti-democratic nature of the current system and bolster worker protections, there must be proactive efforts on the part of policymakers. This includes passing the Workplace Action for a Growing Economy, or WAGE, Act,9 which protects workers by increasing penalties for employers that illegally fire or otherwise retaliate against organizing workers, as well as additional steps to more fundamentally reform the representation process.10

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) was explicitly passed to build worker power. Our elected officials should not shy away from that goal. The current system that workers face in organizing is unfair, and these harmful “reforms” would further tilt the balance of power away from workers. In order to address our country’s pressing problems of stagnant wages and crushing inequality, policymakers must reject efforts to harm workers and their unions and instead commit to rebuilding worker power.

Today’s NLRB elections already disadvantage pro-union employees

Under today’s system, NLRA-covered employees who wish to join together in a union have two options. They can use the first method, known as “majority registration” or “majority sign-up,” where pro-union employees collect a majority of authorization cards from their bargaining unit and then ask their employer for voluntary recognition of the union—typically based on a neutral third-party review of the cards. As the productivity-boosting effects of unionized workplaces often rely on a collaborative relationship,11 voluntary recognition sets employers up for a more productive process than would be established through a contentious election. Even during this process, workers can and often do face pressure from their employer to not form a union.12 If an employer says no to voluntary recognition, workers seeking to form a union have a second option: a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) election.

Step 1 of forming a union: Collecting signatures

Employees who collect signatures representing at least 30 percent of the bargaining unit can call for an NLRB election. However, anti-union employers will often work to prevent workers involved in organizing drives from collecting signatures and thus avoid ever having an election. Employers use similar tactics to stop organizing drives as they use to try to win elections. Approximately three-quarters of employers facing an organizing drive hire anti-union consultants to help defeat the union.13 One anti-union consultant, promoting their “Don’t Sign a Card Interventions,” notes that “with each card stopped your organization takes a step back from the expense, disruption and personal toll of an election campaign.”14 Another argues that “winning an NLRB election undoubtedly is an achievement; a greater achievement is never having one at all!”15 These anti-union interventions during majority sign-up drives show that employers are still able to convey their views on unions to their workers, even without a secret ballot election.

Step 2 of forming a union: Run-up to the election

But if an employer’s anti-union efforts are unsuccessful in stopping an election petition, employers can wield their outsized influence over their workers to an even greater degree during the period leading up to the election. Even though workers eventually mark their decision on a secret ballot, the entire process does not come close to resembling a true democratic choice.16 Employers often attack their employees’ right to organize using a variety of coercive techniques that make the election more akin to sham elections overseas than the U.S. electoral process.

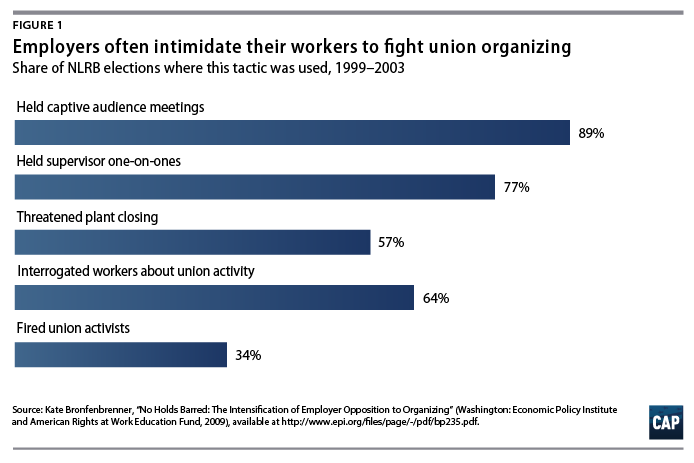

For example, while companies have access to relentlessly present workers with anti-union materials, union supporters do not share the same rights in the workplace. Freedom House, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing democratic rights across the globe, judges whether elections are “free and fair” in part by if candidates can “make speeches, hold public meetings, and enjoy media access throughout the campaign free of intimidation.”17 This is not the case in a union election. Research from Kate Bronfenbrenner shows that nearly 90 percent of employers facing union elections hold “captive audience” meetings, where workers are forced to attend anti-union events.18 At these meetings, employers can tout the futility of union negotiations, suggest that unionization could lead to massive layoffs, or even ignore the logical inconsistencies and make both arguments. During the meetings, pro-union employees can be forced to remain silent under threat of being legally fired.19 More than half of employers effectively threaten plant closings during election drives.20 This does not resemble in any way the two-way “information sharing between workers and employees”21 touted by supporters of bills to eliminate majority sign-up.

While employers can bombard their workers with anti-union messages, pro-union employees face more restrictions around speaking to their colleagues during working hours. And as a general rule, union organizers are unable to set foot on company grounds during the election without employer permission. It is hard to conceive how an election can be considered a democracy if a voter is forced to see posters and literature from only one party at work while employees can be constrained in their ability to gather and speak.

Another key measure of democratic freedom is if individuals’ choices are “free from domination” from powerful groups. Freedom House asks if voters are “able to vote for the candidate or party of their choice without undue pressure or intimidation” and if party members or leaders are intimidated or harassed.22 In workplace union elections, employees are often subject to pressure and intimidation from their employer. Employees are often forced to attend one-on-one meetings with their supervisors about the union—these meetings are used in nearly 4 in 5 election drives, and weekly one-on-ones were used in two-thirds of elections.23 During these meetings, employees sit down with the individual with the power to fire them and must listen to them outline supposed negative consequences of unionization.24 Supervisors cannot legally directly ask employees about their support for the union but are often trained by anti-union consultants on precisely how to discuss union issues and observe workers’ reactions to indirectly determine their employees’ views.25

Pro-union workers are referred to as “disloyal,” the “enemy,” or “troublemakers” by management and can be closely watched and followed by their employers to ensure that they are not able to speak to other workers on the job site.26 Employees identified as being pro-union are often illegally intimidated by their employer—and even fired. Estimates from Bronfenbrenner find that at least one pro-union worker is fired in roughly 1 in every 3 elections.27 Employers face very low penalties for firing pro-union employees—if they are found guilty after the end of a long legal process, they must only pay back pay from the firing to when the verdict is rendered, minus any earnings a worker made elsewhere in the meantime. This cost, which executives sometimes call a “hunting license,”28 is an extraordinarily low cost to pay for an employer considering the chilling effect such firings can have on union drives.

Finally, employers can attempt to influence who is eligible to vote, as described in a publication from the management-side law firm Jackson Lewis P.C., “Create Your Optimal Bargaining Unit – Today.”29 Since supervisors are excluded from the NLRA, employers can change workers’ duties in an attempt to reduce the number of people in the bargaining unit.30 Employers can also make policy changes to attempt to modify whether or not workers form a “community of interest” and thus belong in the same bargaining unit.31

Step 3 of forming a union: Election Day

When election day finally arrives, the election is typically held at the worksite. While neither side can campaign in the room where the ballots are being cast, employers are still free—and encouraged to do so by anti-union consultants—to campaign elsewhere in the workplace as workers are entering the voting booth.32

While the final ballot may be called “secret,” after weeks or months of anti-union campaigning and forced meetings from their employer, most workers’ intentions are not. In fact, by the end of a campaign, anti-union consultants report that supervisors are “astonishingly accurate”33 in predicting the vote count.

Throughout the unionization process, workers are fighting against a rigged system that makes it difficult to gain a foothold at the workplace. While organizers do sometimes succeed—and this success is more likely when using majority sign-up—the balance of power is dramatically tilted toward employers.

Of course, election day does not necessarily end the process of receiving recognition. There may still be legal challenges from either side based on alleged improper conduct.

Step 4 of forming a union: Negotiating a contract

While the process by which workers form and employers recognize a union is important, simply forming a workplace union does not immediately improve workers’ well-being. Focusing on the election process used to form a union obscures the truth about the unionization process, which is quite unlike elections to choose a new mayor or a new representative in Congress.34 Choosing to unionize—whether through signing an authorization card or voting in an NLRB election—is not the endpoint of the process but just the beginning.

Under our current system, simply getting a union recognized by one’s employer or the NLRB does not mean that workers will ever see the benefit of a union contract. This just begins the next step: getting one’s employer to the bargaining table and then successfully negotiating a collective bargaining agreement that can be signed by both sides. Due to the major power differential between even unionized workers and their employers, this can be a long, trying process. Employers, especially those who initially fought the union recognition process, will often fight the collective bargaining process as well. In fact, 62 percent of unions who are certified through NLRB elections do not reach a first contract in one year, and 44 percent do not in two years.35 True labor reform dedicated to improving workers’ rights must address not only the election process but the fairness of the bargaining process as well. The Workplace Democracy Act, sponsored in the 114th Congress by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Rep. Mark Pocan (D-WI), would improve the bargaining process for new unions by bringing management to the table quickly after recognition and providing for first contract mediation and arbitration if both sides cannot come to an agreement.36

Proposed changes from conservatives would rig the election system even more toward employers

Banning workers from unionizing through collecting authorization cards and securing voluntary recognition from their employer—as the recently reintroduced Employee Rights Act by Rep. David Roe (R-TN) does—would be a major blow to workers’ rights.37 These kinds of so-called secret ballot reforms would lock workers in to the undemocratic system laid out earlier in this brief would and require more workers to suffer through the unfair election system to try to gain a voice at work.

As bad as eliminating the possibility of majority registration for a union, the Employee Rights Act, as well as other proposed anti-union “reforms,” would go even further to ensure that employers have the upper hand when workers attempt to band together to improve their workplace.

The Employee Rights Act would require that more than 50 percent of all workers support the union, rather than 50 percent of workers that vote in a union election, and thus count nonvoters as votes against unionization. Redefining “majority” in NLRB would be a radical change that would serve to preserve today’s status quo of unorganized workplaces. This is akin to members of Congress passing a new law stating that in order for a challenger to win their seat, the challenger would have to receive votes totaling 50 percent of all voting age citizens in the district, not just winning a majority of those who cast ballots. Such a threshold would make it nearly impossible for members in contested races to be seated in Congress. Analysis from Celine McNicholas and Zane Mokhiber at the Economic Policy Institute shows that in the 2016 elections, none of the co-sponsors of the Employee Rights Act would have met the very threshold that they are trying to impose on organizing workers.38 In fact, our analysis finds that more than 95 percent of members of the House of Representatives—and more than 99 percent of members challenged by a major party candidate—would have failed to be elected by this standard in 2016.39

Some reform proposals, including the Employee Rights Act, would also require new union elections every three years, or sooner upon the expiration of a collective bargaining agreement, if more than 50 percent of the bargaining unit did not vote in the original union election. This would mean that instead of coming to the bargaining table to decide on the next contract, employers would be once again able to subject their employees to an onslaught of anti-union campaigning. In an especially clear demonstration of the anti-union intention of the bill, unlike a recognition election, these mandatory elections to decertify a workplace union would only require a majority of votes cast—not a majority of bargaining unit members.

In other words, workers would face a higher electoral bar to form a union than employers would face to break a union. And while union workplaces would face automatic elections to eliminate a union, nonunion workplaces would not conversely have automatic elections to form a union. Such an unfair system is a clear mark of an undemocratic process: Freedom House asks if electoral systems have “been manipulated to advance certain political interests or to influence the electoral results.”40 Under the proposed bill, the electoral system would clearly be undemocratic, as it is designed to make it easier for employers to beat back organizing employees. The Employee Rights Act would also provide a host of other anti-union provisions outside of the election process.

Additional laws would also rig the system against workers. The Workplace Democracy and Fairness Act, introduced by Rep. Tim Walberg (R-MI) this year,41 would reverse an important NLRB rule and allow employers to once again delay the union election process, giving them more time to pursue their anti-union efforts. The bill would also change the standard on forming bargaining units to give employers more power to choose their own electorate—making it easier for employers to gerrymander a bargaining unit and place workers not involved in the organizing process into the unit. The Employee Privacy Protection Act, introduced by Rep. Joe Wilson (R-SC), would make it harder for workers to communicate with union organizers but do nothing to limit employer coercion during the union election process.42

Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN) introduced the Protecting Local Business Opportunity Act in 2016, which would establish a definition of “joint employer” that would make it more difficult for workers to bargain with the company that has control over terms and conditions of employment.43 And the Protecting American Jobs Act, introduced by Rep. Austin Scott (R-GA), would prevent the NLRB from issuing rules that affect the substantive rights of employees, employers, and labor organizations—and require the NLRB to review and revise all existing regulations to match this standard.44 This bill would also eliminate the NLRB’s ability to adjudicate unfair labor practices. These changes would make it more difficult for the NLRB to ensure a fair election process for workers.

After expected new anti-worker appointees join the NLRB, the NLRB can also take administrative actions that would make the current union election process harder for workers, such as by allowing employers to delay elections by demanding a hearing on an issue that does not need to be resolved in advance of the election.45

Blocking workers from using majority sign-up to form a union would be bad enough under today’s union election system. But anti-union proposals would go even further:

Redefining “majority” for forming a union

Under the current NLRB election process, a union needs a majority of votes to win an election—the same standard faced by members of Congress. Union opponents have proposed changes that would instead require unions to win a majority of eligible voters. By effectively counting those who do not vote as opposing the union opponents, this rigs the system against union representation.

Allowing companies to once again arbitrarily delay elections

In 2015, the NLRB issued a new election rule that ensured that union elections would happen at a reasonable time period after workers petitioned for an election, and companies would no longer be able to drag out the election process by forcing multiple pre-election hearings.46 Proposed changes—through legislation or the NLRB rule-making process—would reverse this change, allowing companies to once again delay their election date to gain more time to pressure voters.

Limiting unions’ ability to contact voters

The 2015 NLRB elections rule also modernized the election process by granting unions access to modern forms of contact information for voters. Proposed reforms would reverse these gains, stacking the deck against unions in elections by making it harder to contact voters. While employees could opt out to prevent union organizers from being able to contact them, there is no corresponding opt out for pro-union employees to avoid being subject to anti-union communications from their employer.

Introducing automatic decertification votes for unions

By requiring automatic elections to decertify a union on a regular basis, proposed reforms would make it more difficult for workers to organize and effectively negotiate. Once a collective bargaining agreement expired, employers would once again be able to subject their employees to an onslaught of anti-union campaigning instead of coming to the table to negotiate in good faith. No comparable automatic process is provided to allow non-union workers a choice to form a union.

In 2015, the NLRB issued a rule that streamlined the union election process and made it more difficult for employers to delay the election process by forcing a prolonged process of pre-election hearings.47 Employers used these tactics to demoralize workers and drag out the process so that even strongly pro-union employees begin to think the process was impossible. As a management-side attorney explained, “if he could make the union fight drag on long enough, workers would lose faith, lose interest, lose hope.”48 Anti-union proposals would undo these reforms on election timing, restoring another anti-union tactic for employers to use.

Unions have always had rights to contact information of those eligible to vote in union elections. The 2015 NLRB election rule also modernized the election process by including employee’s phone numbers and email address in the voter file, instead of just names and home addresses. As previously mentioned, unions are unable to reach out to workers during working hours, while employers can, so the system is already tilted toward management. The 2015 rule ensured that both sides had a fair opportunity to contact voters outside of the workplace. Union opponents are also looking to overturn this practice. For example, the Employee Rights Act mandates that the voter list would only include names and home addresses.49 And the Employee Privacy Protection Act would restrict union access to voter contact information while providing no way for workers to opt-out of anti-union communications from their employer.50 Members of Congress understand from their election campaigns the importance of phone and email communication—and to limit union access to this information serves only to help employers.

Arguments to force secret ballot elections or allow employer delays are unfounded

Past and current sponsors of legislation to end majority sign-up do not explicitly state that their goal is to reduce worker power and further advantage employers. In fact, when introducing the 2015 version of the Employee Rights Act, then-Rep. Tom Price (R-GA) actually claimed that the bill would not “make it more difficult to join” a union.51 Similarly, Sen. Alexander claims that allowing employers to once again delay elections will “restore workers’ rights.”52 And 2017 Employee Rights Act sponsor Rep. Roe frames his bill neither “pro- or anti-union” but as a way to “protect and promote the rights of America’s workers.”53

The arguments that conservative advocates use to make their case for reforming the union election system are not backed up by the facts. As shown below, these reforms are not necessary to protect workers’ rights and would indeed further weaken their right to organize.

Secret ballots do not actually provide voters secrecy from their employer

Requiring a secret ballot for union elections may seem at first glance to be a fair way to protect workers from employer intimidation. It is more difficult to intimidate voters when powerful groups do not know who someone is voting for. However, the coercive workplace atmosphere in which NLRB elections take place makes this impossible—and a secret ballot does not ensure a secret vote.

As previously described, employees are carefully monitored during organizing drives and in the weeks before a union election. They are forced to attend mandatory one-on-one meetings where supervisors are trained not only to push anti-union messages but also to indirectly determine how an employee is planning on voting. After repeated meetings like this, managers have a very good idea of the vote before any ballots are cast. One anti-union consultant stated that he would offer a prize to the manager with the closest guess on the final vote tally, and that “in pool after pool the supervisors were astonishingly accurate.”54

Majority registration or sign-up methods do not result in union or employer abuse

Proponents of eliminating the majority sign-up option for unions claim that “anecdotal evidence suggests that signed agreement cards are often obtained through deception, coercion, and intimidation of employees.”55 However, research from the University of Illinois, Rutgers University, Cornell University, and the University of Oregon, which examined 1,359 union drives that led to more than 34,000 public sector workers joining together in a union, found this claim to be completely unfounded. During these drives, there were only five allegations of improper union behavior, and none were confirmed.56

Majority sign-up procedures do not restrict companies from making their views known on unions

Anti-union lawmakers argue that forcing a secret ballot election “gives both the union and the employer an opportunity to communicate their perspective on union membership to employees and ensures that workers are able to make informed decisions.”57 To claim that, without this reform, employers do not have the opportunity to let employees know how they feel about union membership is laughable. Employers have every opportunity to make their anti-union views heard and often do even prior to organizing drives during new employee orientation. 58

Prompt union elections do not prevent workers from making an informed decision on unionizing

Former Rep. John Kline (R-MN), a previous sponsor of a bill to roll back NLRB reforms to ensure that employees have an election after petitioning to form a union without unnecessary employer delay, claims that such timely elections “cripple worker free choice.”59 It is important to remember that organizing drives do not start with an election. And under the new NLRB election rules, during an election with the median number of days between a petition and election in 2016, workers still had more than three weeks of notice before the eventual election—plenty of time to consider their options.60

And efforts to repeal the NLRB reforms are certainly not concerned with giving unions the opportunity to make their case on the benefits of membership, as their provisions make it more difficult for unions to reach out to workers. For example, the Employee Rights Act would undo NLRB election modernization efforts and prevent unions from receiving email addresses of bargaining unit employees before elections.

Employers have nearly unchecked power to ”communicate their perspective”61 on unions to their workers. And as unions can lead to increased worker power—and subsequently, increased worker pay and benefits62—employers are incentivized to do so even before an election is called. Even during majority sign-up campaigns, employers work to persuade their employees—as evidenced by consultants’ insistence that employers should prevent elections from happening. If employees take this into account, and still choose to sign an authorization card and start the process of building a union and negotiating collectively at their workplace, they have already made an informed decision. Proposed changes to the electoral process from conservative politicians would serve only to further tilt the balance against workers who choose to join together—ensuring that corporate power and corporate profits stay in the hands of those at the top.

Conclusion

The National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935 in order to address “the inequality of bargaining power” between employees and employers. The preamble of the act explained that this inequality of power led to “depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of wage earners in industry,” and that the policy of the United States was “encouraging the practice and procedure of collective bargaining.”63

Any neutral observer can see that, today, workers face a similar dearth of bargaining power. The fissuring of the workplace has turned once-valued employees into commodities, as subcontracted businesses compete with contracting firms to provide labor at the lowest cost. This makes it difficult for workers to negotiate with the firm that actually determines the terms and conditions of one’s employment. Many sectors in the U.S. economy are becoming more concentrated, with the market becoming dominated by a small number of very powerful firms.64 This decline in competition hurts workers in two ways: Companies can exercise their monopoly power by raising prices and use their monopsony power to keep wages down. Globalization also can take its toll on wages, as companies use outsourcing as a way to avoid providing good-paying jobs at home.

This has led to slow wage growth for the typical workers and a huge concentration of income among society’s richest members. In 1935, the top 1 percent of income earners brought home 16.7 percent of the nation’s income.65 Today, our economy is even more out of balance: The top 1 percent bring home an incredible 22 percent. 66

All of these challenges are compounded by declining union strength. Strong unions bring democratic voice to the workplace, ensure that workers share in the gains of their employers, and fight for a political system that protects workers broadly. As unions have weakened over recent decades, corporations have had a much freer hand in the workplace and the larger economy.

Policymakers should be focused on rebuilding worker power—not making it harder for them to come together in unions. Any legislative or regulatory effort to make it more difficult for workers to gain a voice and power at their workplace should be opposed.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Alex Rowell is a research associate for the Economic Policy team at the Center. Gordon Lafer is a professor at the University of Oregon’s Labor Education and Research Center.

Endnotes