In recent decades, U.S. economic growth has not been broadly shared. Despite today’s low unemployment rates and almost record-high corporate profits, many workers have experienced stagnant pay. Wage growth over recent decades has been especially poor for those without four-year college degrees—those in the working class. Since 2000, their weekly compensation has grown by just 3 percent in real terms, less than half the rate of wage growth for those with a at least a bachelor’s degree.

In today’s America, the working class is more diverse than ever and increasingly consists of workers working nonindustrial jobs. Yet, when the working class is discussed in today’s political environment, at times only some workers are included. President Donald Trump’s rhetoric on the campaign trail was targeted toward white male members of the working class, for example, and he typically referred to industrial jobs. And some politicians explicitly or implicitly call on prioritizing winning the votes of white members of the working class. Yet previous CAP Action analysis found that policymakers may best reach the entire working class by advocating for an agenda that improves the economy for all members: Across racial and ethnic lines, members of the working class support progressive economic policies.

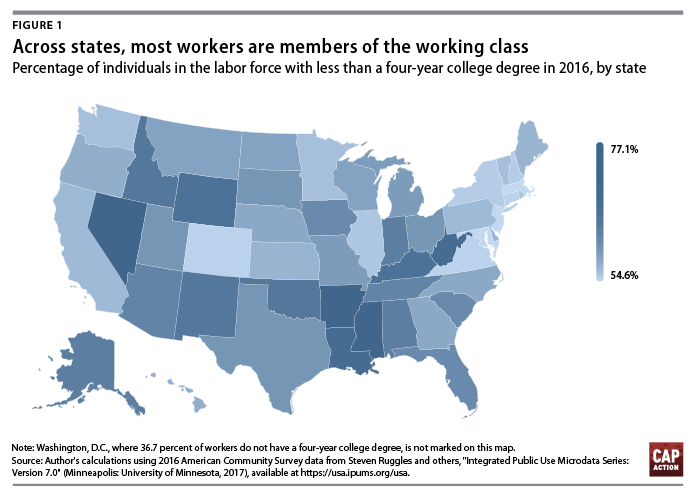

This column takes a state-by-state look at the demographics and employment of the U.S. working class using 2016 American Community Survey data from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS).

Defining the working class

For the purposes of this column, “working class” is a term used to define members of the labor force with less than a four-year college degree. There is no clear, agreed-upon definition of the working class, and the class in which individuals place themselves is often related to their education, income, and occupation. For this analysis, an education-based definition is used, since this is more stable across one’s lifetime than is income or occupation. For more on this definition, see this issue brief from the CAP Action Fund.

Ensuring that the economy works for those without a bachelor’s degree is crucially important, since, as shown in Figure 1, members of the working class make up a sizable majority of today’s workers. The working class makes up the largest share of the labor force in Nevada, at 77.1 percent; Mississippi, at 75.9 percent; and Arkansas, at 74.9 percent. In all states but four—Massachusetts, at 54.6 percent; New Jersey, at 58.2 percent; Maryland, at 58.9 percent; and Connecticut, at 59.2 percent—more than 6 in 10 workers have less than a four-year degree.

Demographics of the working class

Women make up a substantial share of the working class in every state and Washington, D.C. Table 1 shows that the share of those in the labor force who are women without a four-year college degree ranges somewhat among states, from 41.1 percent in Alaska to 47.9 percent in Delaware. In 41 states, the female share of the working class is between 44 and 47 percent. In Washington, D.C., the number is slightly higher, at 52.6 percent.

In every state but Maine, Vermont, and West Virginia, the working class is more racially and ethnically diverse than each state’s overall adult population. Nationally, this overrepresentation is driven by two major trends: White Americans are more likely to hold a four-year college degree, and a greater share of white Americans are older than the prime working age. In eight states—Hawaii, California, New Mexico, Texas, Nevada, Maryland, Florida, and Arizona—and Washington, D.C., workers of color make up the majority of the working class. In another nine states, workers of color make up at least 4 in 10 members of the working class.

Sectors in which the working class is employed

In every state and Washington, D.C., the vast majority of employed members of the working class can be found in service sector jobs. Industrial jobs—those in the goods-producing industries of construction, manufacturing, and mining—make up a smaller share of working-class employment: between 11.9 percent in Hawaii and 28.9 percent in Indiana. But while the typical working-class worker is likely not employed in an industrial field, there is a major reason why politicians tend to highlight these types of jobs: They are often of higher quality than jobs in other sectors, with workers receiving higher pay. Workers in these fields are also more likely to work full time for the entire year.

As shown in Table 2, across most states, industrial jobs tend to offer higher pay for full-time employment than do service or agricultural jobs. This is in part because workers in the industrial sector hold more power. Historically, these types of jobs were more likely to be unionized than service sector jobs, and they remain so today even as union density has fallen. Higher unionization rates mean that more workers in these fields have the ability to bargain collectively for their pay and place more pressure on nonunion firms to raise pay to attract workers.

Conclusion

Policymakers must take action to ensure that all members of the working class are able to thrive in today’s economy—no matter their race, ethnicity, gender, or the industry in which they work. Today’s challenges call for major investment in the American people and comprehensive reforms to the U.S. economy. Policymakers should support workers’ ability to join together in unions and should enable new forms of collective bargaining above the individual firm level. Workers should have access to affordable child care and modern work-family policies that allow parents who wish to fully participate in the labor force to do so. And government should act to address national challenges and employ millions of workers in high-quality public jobs across the country. The resulting tight labor markets would also help boost wages in the private sector. Such a pro-worker policy agenda would be especially beneficial to those in today’s broad, diverse working class.

Alex Rowell is a policy analyst for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress Action Fund.