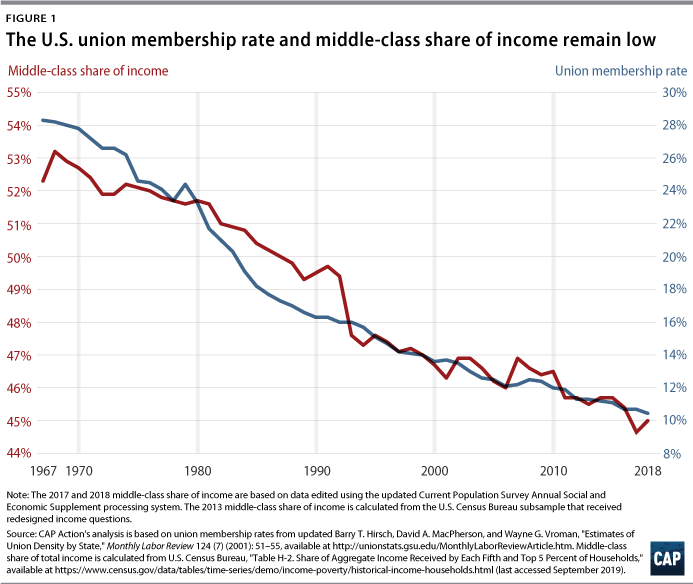

Workers’ incomes may finally be slightly above the level they were in 1999, but the share of income going to the middle class remains low. New data from the U.S. Census Bureau show that the middle 60 percent of households, by income, took home just 45 percent of national income in 2018, basically unchanged from 2017, when they earned a record low 44.7 percent. In contrast, the share of income going to the highest-income households remains at a near record high. This decadeslong trend of growing inequality is closely related to the decline of American unions. As union membership rates dwindle, prospects for the middle 60 percent of American households shrink as well.

Figure 1 shows this trend. In 1967, when 28.3 percent of American workers belonged to a union, 52.3 percent of national income went to middle-class households. (see Figure 1) But over the past five decades, both those numbers have steadily declined. In 2018, just 10.6 percent of American workers were unionized, a record low, and only 45 percent of income accrued to the middle class—less than in 1967.

While the middle class has lost ground, the share of income going to America’s wealthiest households has skyrocketed. In 2018, the top 20 percent of households by income took home more than half of total U.S. income—almost 20 percent more than in 1968. And the share of income going to the top 5 percent grew even more, rising from 17.2 percent in 1967 to 23.1 percent in 2018.

To be sure, weakened unions are not entirely to blame for these trends. Since the 1980s, global competition, corporate consolidation, and changes in tax law that favor the wealthy but do little to increase business investment have all worked to wrest economic power from workers. Additionally, the U.S. economy has spent far less time at full employment in recent decades than it did from 1949 through 1979—a period during which union membership rates were higher—which has weakened the bargaining position of middle- and low-wage workers. Still, there is clear evidence that lower union membership has contributed to rising income gaps and a shrinking middle class.

Unions strengthen the middle class

Unions play a major role in constraining income inequality and fortifying the middle class. Indeed, sociologists Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld estimated in 2011 that the decline in unions explains one-third of the growth in wage inequality among men in the United States. Research also suggests that, at least in certain industries, union decline may be a bigger contributor to wage inequality than market forces such as computerization.

Unions help workers in many ways. Unions workers make roughly 12 percent more, on average, than similar nonunion workers, and they are more likely to receive benefits such as employer-provided health insurance, a workplace retirement plan, and paid leave. In addition, unions can help narrow pay gaps for women and people of color, in particular Black and Hispanic workers. When unions are strong, everyone benefits. For instance, regions with high union membership have lower rates of working poverty and tend to have greater economic mobility for low-income children.

Moreover, unions make democracy work better by acting as a counterbalance to corporate power in politics and encouraging the democratic participation of workers. Indeed, unions are one of the few types of interest groups whose positions consistently line up with the economic interests of the working class.

Corporate attacks continue to weaken unions

A 2018 Gallup poll found that 62 percent of U.S. adults approve of labor unions—a 15-year high. But despite the fact that a majority of Americans support unions, only 10.6 percent of the workforce belonged to one in 2018. Union density today is roughly one-third of what it was in the mid-1960s and is almost as low as it was in 1930, prior to the passage of the National Labor Relations Act.

Unions’ role in raising worker pay and fighting for pro-worker policies has made them a target of corporate interests. In recent decades, employers have become increasingly aggressive in their efforts to avoid unionization in the private sector, and the majority of workers encounter serious opposition when they try to organize. What’s more, in recent years, the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission ruling, which eased restrictions on political spending, further accelerated political attacks on unions.

Public policies have also played a significant role in union decline. Since 2010, six states have passed “right-to-work” laws, which prohibit unions from compelling workers to become members as part of their job or otherwise requiring fair-share fees to cover the costs of negotiating a collective bargaining agreement. In addition, several states have launched targeted attacks against their public sector unions. Wisconsin—which virtually eliminated collective bargaining for most government employees in 2011—saw public union membership fall by more than 50 percent as a result. In June 2018, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) delivered another blow to public sector labor unions by banning all fair-share fees in the public sector.

The current administration is further enabling employers to avoid unionization. For instance, President Donald Trump’s National Labor Relations Board appointees have made it easier for companies to misclassify workers as independent contractors exempt from federal labor law protections and are also working to roll back joint employer protections, which would impede the ability of workers employed by subcontractors and franchises to hold employers liable and form unions.

Even with these trends, however, there are indications that workers are fighting back. In 2018, 485,000 workers went on strike—the highest number since 1986. They joined picket lines outside grocery stores, hotels, and schools—and even on cellphones. Pro-worker policymakers have also increasingly been promoting unions. Members of Congress have introduced legislation such as the Protecting the Right to Organize Act—which would increase penalties on companies and employers that break the law, ban right-to-work laws that undermine union finances, and enhance the ability of workers to strike—as well as the Public Service Freedom to Negotiate Act, which would ensure that all public sector workers have collective bargaining rights. State policymakers in states such as Washington and New Jersey have also contributed, passing a number of bills to ensure that public sector workers are able to join together in strong unions. And Seattle’s significant Domestic Worker Bill of Rights took additional steps toward protecting workers historically excluded from labor laws.

Conclusion

Strong unions help ensure that middle-class families receive a fair share of the economic growth that they create. Policymakers at both the state and federal levels must take steps to ensure that all workers—including agricultural and domestic workers, independent contractors, gig workers, and government employees—have strong rights and powers that enable them to join a union and bargain collectively. They should also act to modernize the U.S. labor law system to allow workers to come together and bargain across entire industries or regions—rather than just at the firm level—and create incentives for union membership by involving unions in training and enforcement activities. Taking these steps will bolster both unions and the middle class.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. Malkie Wall is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Action Fund.

Authors’ note: CAP uses “Black” and “African American” interchangeably throughout many of our products. We chose to capitalize “Black” in order to reflect that we are discussing a group of people and to be consistent with the capitalization of “African American.”