The latest data from the U.S. Census Bureau show that typical American households are finally seeing their incomes grow since the recession. The median household income jumped from $53,718 in 2014 to $56,516 in 2015, an increase of 5.2 percent. Notably, gains in income were broadly shared in 2015, with lower- and middle-income families seeing faster gains than the rich. However, there is much ground to make up: The share of national income accruing to the middle class remains near record lows.

Unions can help rebuild the middle class. When working people join together in unions, they are better able to secure a fair share of income. Unfortunately, the proportion of American workers joined in unions has declined dramatically over recent decades. In 2015, a little more than 11 percent of U.S. workers were union members, the lowest share since the passage of the landmark National Labor Relations Act in 1935. Without strong unions, workers lose power in the workplace and in the political realm, weakening their ability to negotiate for higher wages and beneficial public policies for the middle class.

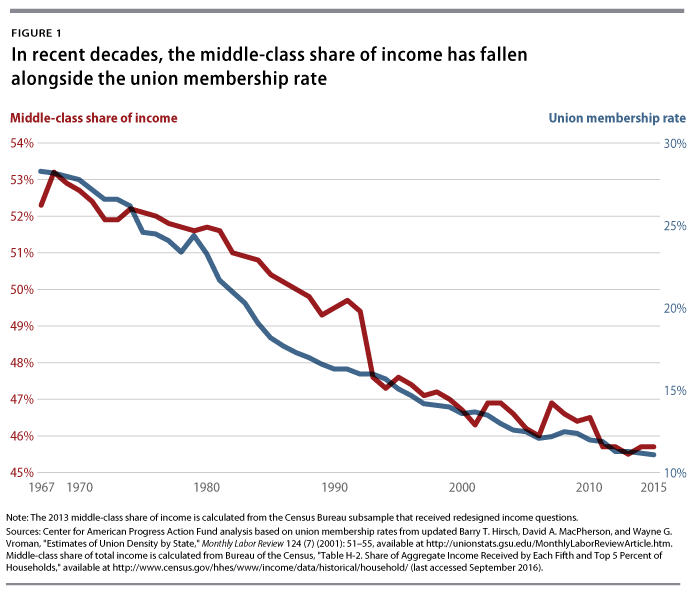

As a result, the fates of the middle class and unions are closely intertwined. As Figure 1 shows, the share of national income earned by the middle 60 percent of American households has declined dramatically in the past 48 years alongside the union membership rate. While the middle class brought home more than 53 percent of national income in 1968, the middle 60 percent accrued less than half—45.7 percent—of income in 2015. In that same time span, the income share climbed from 42.6 percent to 51.1 percent for the top 20 percent and rose from 16.3 percent to 22.1 percent for the top 5 percent. Had the middle-class share not declined over past decades, the average middle-class household would be making $9,900 more annually.

This is not to say that the decline of unions is the sole contributor to rising inequality and the falling middle-class share of income over recent decades. Global competition, increasing levels of market concentration, and policies that benefit the wealthy few at the expense of middle-class and lower-income Americans have all played a part. But the effect of declining worker power is substantial. Research from the United States and advanced economies worldwide shows that the decline of unions is associated with increased inequality.

Unions help combat inequality and boost middle-class incomes in part through the benefits they bring to their members. Thanks to increased bargaining power, union members’ wages are on average about 14 percent higher than comparable nonunion workers. And unions also help secure key components of a middle-class living: Their members are more likely to have retirement benefits, health insurance coverage, and paid leave.

But the benefits of unions do not just extend to their members. When unions are strong, they help set the standards for a given region and industry, encouraging nonunion employers to raise their wages in order to compete for workers. In fact, recent research estimates that had U.S. union membership remained at 1979 levels, the average nonunion, full-time, private-sector male worker would have earned an additional $2,704 in 2013. Center for American Progress research has found that unions are associated with increased economic mobility, as children of union fathers on average make more than those of nonunion fathers. These effects on mobility extend beyond one’s children: Low-income children who grow up in an area with higher union density tend to have relatively higher incomes as adults than kids who grow up in areas without many union members. Another CAP analysis found that about one-third of the decline in the share of U.S. workers who are middle class from 1984 to 2014 is explained by falling union membership.

These benefits to nonunion members can be explained in part by unions’ political influence. Unions are among the few interest groups that stand up for middle-class interests, providing a crucial counterbalance to the attempts of the wealthy to influence policymakers. Unions also get more Americans involved in the political process through voter mobilization efforts and more. For example, the Fight for 15 movement, with union support, has helped lead the charge for states to raise their minimum wages. Twenty states raised their minimum wages at the start of 2015, and these new census data show that incomes have grown fastest for those in the bottom 20 percent of incomes.

Encouraging continued and stronger income growth for the middle class and those working to join it will require a broad progressive economic agenda. All Americans should have a higher minimum wage, guaranteed paid family leave and paid sick days, and access to affordable, high-quality child care and higher education. Policymakers should invest in infrastructure to create jobs now and prepare the economy for faster economic growth.

But it is critical that any attempt to rebuild the middle class also includes restoring worker power. It should be easier for workers to come together and negotiate collectively, and policymakers should also revamp the U.S. labor relations system to enable higher-level bargaining across industries. When unions of working people are stronger, the middle class is stronger.

Alex Rowell is a Research Assistant with the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund. David Madland is a Senior Advisor to the American Worker Project.