This piece is an update of a 2017 column.

New data from the U.S. Census Bureau show that in 2017, the share of income earned by the middle 60 percent of households, by income, remained near record lows. In contrast, the share of the nation’s income going to high-income households has increased sharply over recent decades, and in 2017, it remained at record highs. A revitalized union movement could help reverse this decadeslong trend of growing inequality and a shrinking middle class.

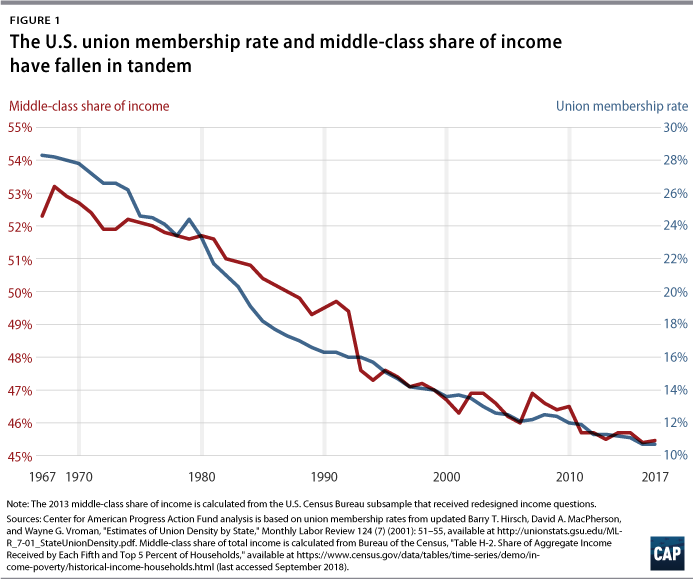

The fate of the middle class is directly tied to the strength of American unions. Figure 1 shows how union membership rates have fallen over the past 50 years, along with the share of income that goes to the middle 60 percent of American households. In 1968, this group of households brought home 53.2 percent of national income. That same year, 28.2 percent of American workers were union members. As union membership rates began to slide downward, so too did the share of income accruing to the middle class. In 2017, just less than 11 percent of American workers were unionized, and the middle 60 percent of households now earn just 45.5 percent of national income, barely up from 45.4 percent in 2016, a record low share.

Over this same time period, the share of income earned by the richest households climbed dramatically. The richest top 20 percent of households earned a majority of U.S. income in 2017—51.5 percent—while in 1968 they earned just 42.6 percent. The top 5 percent of households saw their share grow from 16.3 percent to 22.3 percent over this same period. And these estimates may actually underestimate inequality. For example, Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty’s analysis of tax data found that the top 1 percent of households alone brought home 22 percent of the national income in 2015.

How unions strengthen the middle class

This growth in inequality cannot be entirely attributed to falling unionization rates. Low- and middle-income Americans have faced challenges on a variety of fronts. In the years after 1980, the U.S. economy has reached full employment less than half as often as it did from 1949 to 1979, resulting in decreased worker bargaining power. Increased global competition and corporate consolidation have also made it harder for the typical worker to get ahead.

Still, the evidence is clear that reduced union membership contributes to greater inequality and strengthens the middle class. The decline of unions and collective bargaining is responsible for roughly one-third of the rise in inequality among male workers over recent decades, according to research by Harvard University’s Bruce Western and Washington University’s Jake Rosenfeld. A study from the International Monetary Fund found that a 10 percentage-point drop in union density was associated with a 5 percent increase in the income share earned by the top 10 percent.

Unions help workers and the middle class on many fronts. When workers join together in a union, they increase their bargaining power in the workplace and are able to negotiate for higher pay and better benefits. The typical union worker earns nearly 14 percent more than a similar nonunion worker and is more likely to have important benefits such as employer-provided health insurance, a workplace retirement plan, and paid time off. Collective bargaining can be particularly powerful for groups that face discrimination—such as women and people of color—by creating fair processes, raising wages, and closing pay gaps.

But unions do far more than just help their members. They also help make the economy better for all workers. When enough workers in an industry or region are able to bargain collectively, nonunion firms tend to raise their wages as well. Research from the Economic Policy Institute found that had union membership rates stayed at their 1979 levels, the average nonunion man working year-round in the private sector would earn about $2,700 more each year. Unions also help boost economic mobility not only for their members but also for entire regions.

When workers unionize, they make politicians more responsive to the concerns of ordinary Americans and provide a key political counterbalance to wealthy special interests. Mobilization efforts by unions boost voter turnout. Unions are among the only interest groups that fight for the interests of middle-class households, working against wealthy special interest groups attempting to rig the nation’s economy against workers. The union-backed Fight for $15 movement has successfully pushed states and local governments across the country to raise the minimum wage.

In short, unions help give workers a voice and power in the U.S. economy and democracy.

Corporate interests have intensified their attacks against unions

A 2017 Gallup poll shows that 61 percent of Americans approve of labor unions—an approval rating similar to that of the 1970s and 1980s. Yet despite generally positive approval ratings over the past several decades and polls showing that a majority of workers would like to join a union, the share of unionized private sector workers has fallen sharply. Today, just more than 6 percent of private sector workers are union members, which is about as low as union density has been since the National Labor Relations Act was passed in 1935 and lower than the roughly one-third of unionized private sector workers in the 1950s.

As a result of their ability to raise worker pay and fight for pro-worker policies, unions and their members have been targeted by corporate interests. The past 40 years have seen increased corporate efforts to break unions in the private sector workplace, and many workers face incredible opposition when attempting to form a union at their job. However, attacks on unions have been intensifying in recent years, following the ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that eased limits on corporate political spending.

Since 2010, six states have passed right-to-work laws, which prohibit unions from requiring fair-share fees that ensure that workers who benefit from collective bargaining pay for bargaining costs. Wisconsin effectively eliminated collective bargaining rights for most public sector employees in 2011. As a result, the share of Wisconsin public sector workers in a union fell by more than half from 2010 to 2016. Iowa passed a similar law in 2017, and the U.S. Supreme Court struck another blow against public sector unions by outlawing fair-share fees in the public sector.

But workers are not taking these attacks sitting down. This year, workers have shown surprising strength fighting back. For example, teachers in a number of states have gone on strike to raise wages and improve public education, voters in Missouri defeated a so-called right-to-work law in a ballot initiative, and the city of Seattle passed a bill to create a new type of collective bargaining for domestic workers.

Conclusion

Strong unions are essential to helping working- and middle-class families receive a proper share of the country’s economic growth. Policymakers must stand with workers and against the corporate agenda that seeks to destroy unions by fighting harmful bills that serve to make it even harder for workers to join together. They should also take bolder steps to modernize the U.S. labor law system to build power for workers to ensure that they have rights on the job; the ability to bargain collectively across an entire industry, not just at the firm level; and strong incentives to join unions. Policymakers at both the state and federal levels should make rebuilding worker power their top priority.

David Madland is a senior fellow and the senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress Action Fund.